In the midst of a fully tech-centric Smart City World Expo, Ruha Benjamin’s talk, titled “Utopias, Dystopias, or UStopias: Whose Imagination Are We Living In?”, was a rare gem. While much of the expo focused on cutting-edge technological solutions for urban living, Benjamin reminded us that “smart” doesn’t only apply to technology but to community intelligence, too. Moderated by Femi Oke, with Benjamin, a Professor of African American Studies at Princeton, as the keynote speaker, this session brought a grounding perspective to the event, challenging us to see beyond the high-tech solutions and recognize the potential for collective wisdom and social equity to shape our urban futures.

Benjamin opened her talk by quoting Black feminist writer Toni Cade Bambara: “Not all speed is movement,” a call to reconsider the breakneck pace of tech-driven change. She emphasized that while innovation surges forward, critical voices and vulnerable communities are often sidelined. Highlighting the crises of today—whether through geopolitical violence, socio-economic disparities, or the climate policies exacerbating extreme weather—she argued that technological advances alone do not ensure societal progress. Instead, innovation must be held to higher standards of equity, justice, and transparency.

This call for critical engagement set the stage for a nuanced discussion of two prevailing narratives around technology. On one end is the techno-dystopian view, where technology is seen as a threat that erodes personal agency, displaces jobs, and strips individuals of autonomy. On the other is the techno-utopian ideal, which casts technology as the cure-all for societal issues, making our world more efficient and egalitarian. Benjamin noted a common flaw in both perspectives: they often view technology as an autonomous force, sidelining the people, values, and intentions that create and control these systems. Rather than seeing technology as inevitable or preordained, she argued that we must “remove the screen” to reveal the human agents and power dynamics behind the scenes.

Benjamin illustrated this with the example of the Community Innovation Project in Saint Paul, Minnesota, a data-driven collaboration between local schools and law enforcement aimed at identifying “at-risk” youth. Despite its seemingly positive language of “innovation” and “community,” residents voiced concerns over data usage and the intentions of the institutions involved, which they felt had historically failed local youth. After organized protests, the community successfully halted the project and advocated for reallocating resources directly to the needs of young people without the stigmatizing label of “at-risk.” Here, Benjamin underscored the necessity of both critique and creativity: knowing not just what we oppose, but also envisioning what we want. It is only through this dual lens, she argued, that we can push against the status quo, which often distorts our worldviews and perpetuates inequality.

Taking a global perspective, Benjamin pointed to how unspoken hierarchies are embedded in various societies, from colorblind policies in France to racial stratification in Brazil and caste dynamics in India. These systemic inequalities often hide behind the promise of neutrality or even benevolence, but they shape access, opportunity, and power in profound ways. “What kind of intelligence is shaping our future?” Benjamin asked, challenging us to question whether it is an intelligence rooted in social awareness and equity, or a top-down approach that falsely believes it can “solve” structural problems through technology alone.

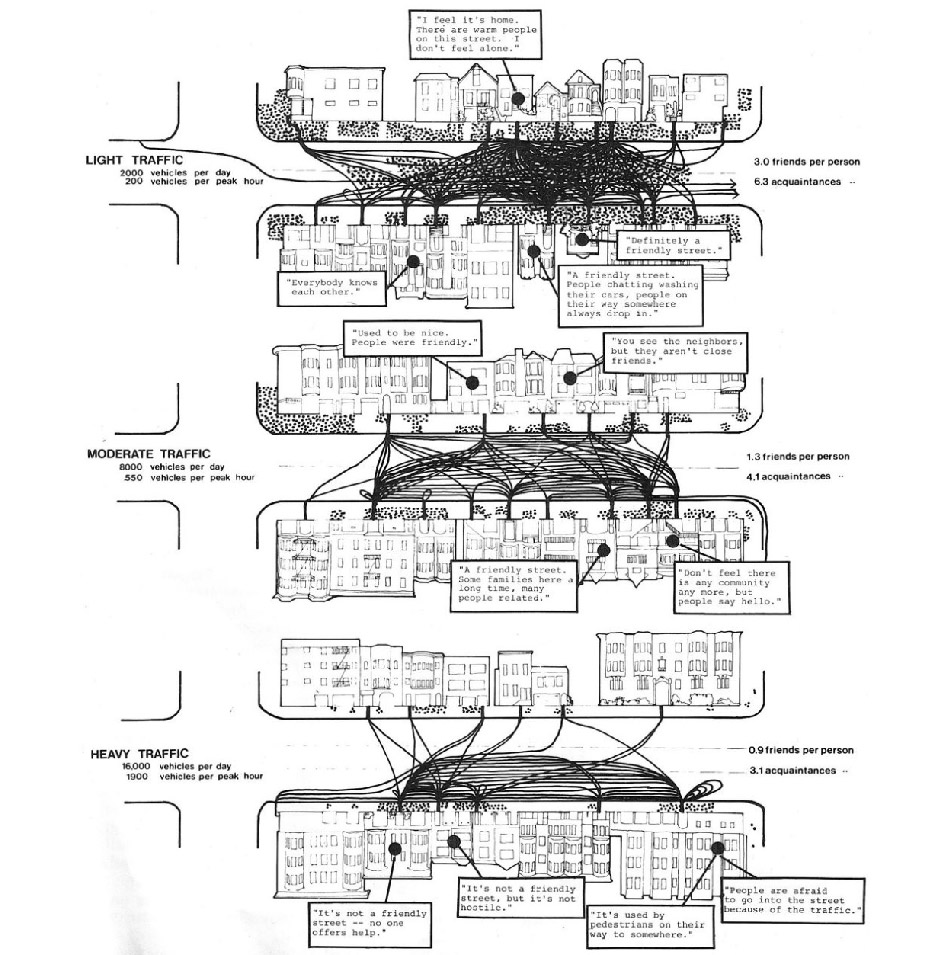

One subtle yet powerful example Benjamin cited was the hostile architecture commonly found in public spaces. She described a visit to San Francisco where she saw benches with dividing bars, designed to prevent people from lying down. This design is part of a broader trend of “exclusive” urban spaces that, under the guise of safety or functionality, exclude specific groups, particularly the homeless. From spiked benches to individual seating, hostile architecture illustrates how public spaces are subtly, yet deliberately, shaped to dictate who is welcome and who is not.

Benjamin also addressed state surveillance in so-called smart cities, where technologies like facial recognition and drones are deployed not only to monitor migrants but to control urban residents. Such tools, she argued, often reinforce racial and social hierarchies. She pointed to recent cases in Germany where social media surveillance has been used to deny rights or revoke citizenship of individuals supporting liberation movements, such as for Palestine. These surveillance practices, marketed as security measures, often reflect underlying biases and serve to maintain unequal power structures.

The talk culminated in the concept of “ustopia,” a term coined by author Margaret Atwood that merges “utopia” and “dystopia” to suggest a hybrid reality shaped collectively. Benjamin proposed that unlike utopias or dystopias, which seem to happen to us, ustopias are spaces we actively create, envisioning realities where inclusivity and justice are prioritized. This “grammar” of ustopia, she argued, offers a powerful framework for resistance and transformation. She shared a story of a French village where residents rejected hostile benches and advocated for an inclusive public space, an example of how communities worldwide are already challenging exclusionary norms and reimagining their environments.

To close, Benjamin called for a reclamation of collective imagination as a tool for social transformation. She critiqued the notion of “artificial intelligence” as a one-size-fits-all solution and urged instead for a mindset of “abundant imagination.” Drawing on ancestral knowledge and community wisdom, she envisioned a future where technology doesn’t alienate but empowers, harmonizing with people and the planet rather than dominating them.

In this expansive exploration, Benjamin left the audience with a powerful challenge: to rethink the systems shaping our lives and to take an active role in designing a society that values interdependence and equity over speed and scale. Her call to action invites each of us to be co-creators of a more humane, inclusive, and just future.