Embracing Diversity

The Role of Public Spaces in a Changing World

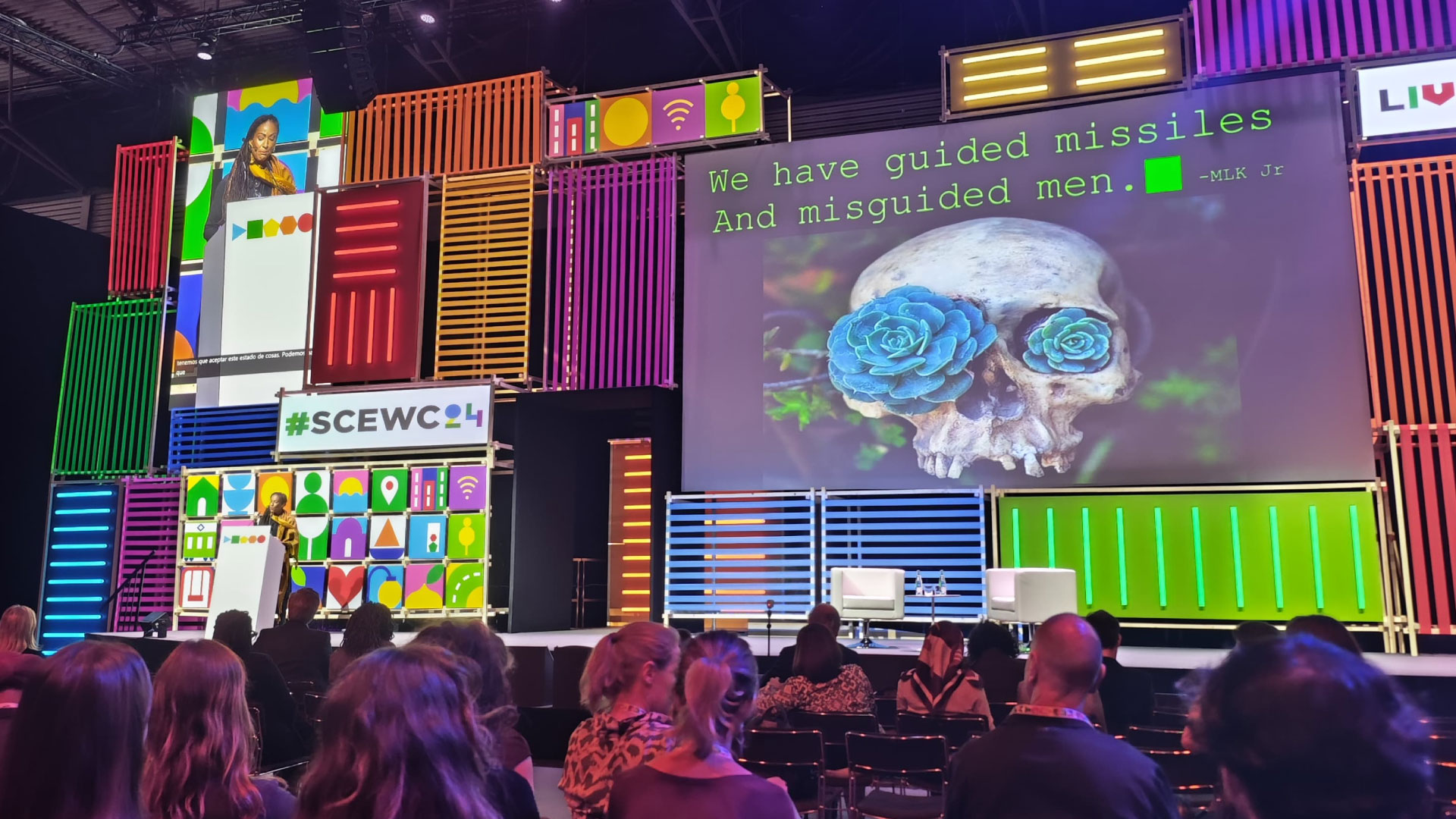

In a world marked by constant change, where the lines between migration and rootedness blur, and where the intersection of identities weaves a complex tapestry, we find ourselves in a time of both harmonization and dissonance. We are, as Amin Maalouf suggests, all in a sense migrants, navigating a universe that bears little resemblance to the place of our birth. Our identities, once solid and unchanging, are now fluid and evolving throughout our lifetimes.

As Wilhelm Reich profoundly stated, “You think the end justifies the means, however vile. I tell you: the end is the means by which you achieve it. Today’s step is tomorrow’s life. Great ends cannot be attained by base means. You’ve proved that in all your social upheavals. The meanness and inhumanity of the means make you mean and inhuman and make the end unattainable.” Reich’s words emphasize the profound link between the means and the ends in the journey of identity. It’s a reminder that the path we choose matters as much as the destination.

The concept of identity, deeply intertwined with the idea of migration, is in a state of constant flux. We are shaped not only by our roots but by the environments we find ourselves in. Identity is a construct that continually adapts as we encounter new cultures, languages, and ideas. As Maalouf points out, being a migrant is not limited to those who have been forced to leave their native lands; it now encompasses a broader definition. We all must learn new languages, adapt to different modes of speech, and internalize codes that are alien to our original identities.

This process of evolving identity often leaves us feeling torn, caught between the land we left and the land we’ve embraced. Embracing a new culture is not an act of betrayal, but a complex negotiation that involves navigating a range of emotions. The new culture may be one of rejection, a response to repression, insecurity, or lack of opportunity. Yet, the act of leaving behind a part of one’s identity, even when it is rooted in challenging circumstances, carries a sense of guilt and sadness.

However, the essence of a harmonious society lies in the acceptance of all identities. As Maya Angelou eloquently puts it, “We all should know that diversity makes for a rich tapestry, and we must understand that all the threads of the tapestry are equal in value no matter what their color.” Diversity is not just a matter of ethnicity or race but also encompasses gender, religion, language, sexual orientation, and more.

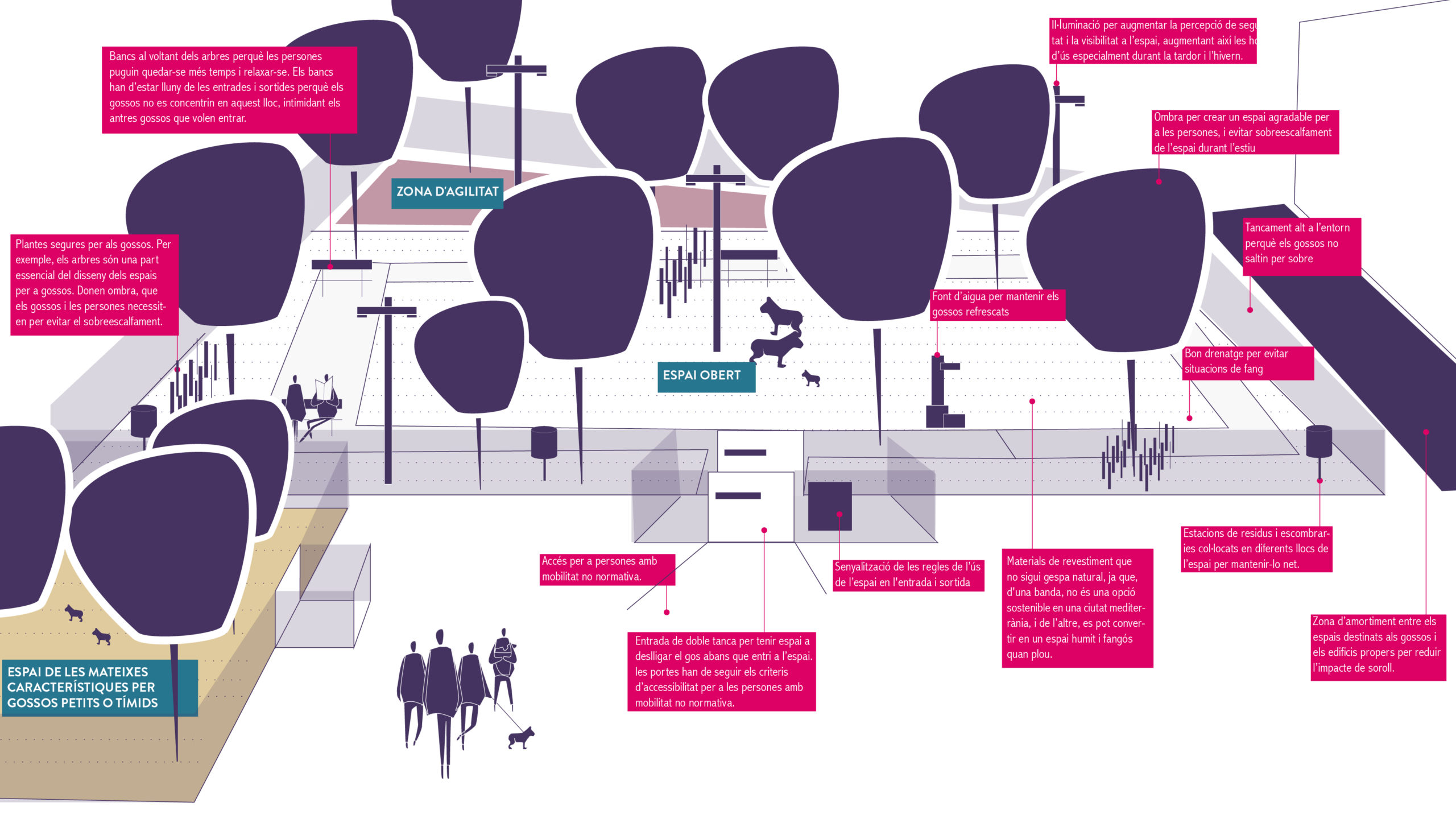

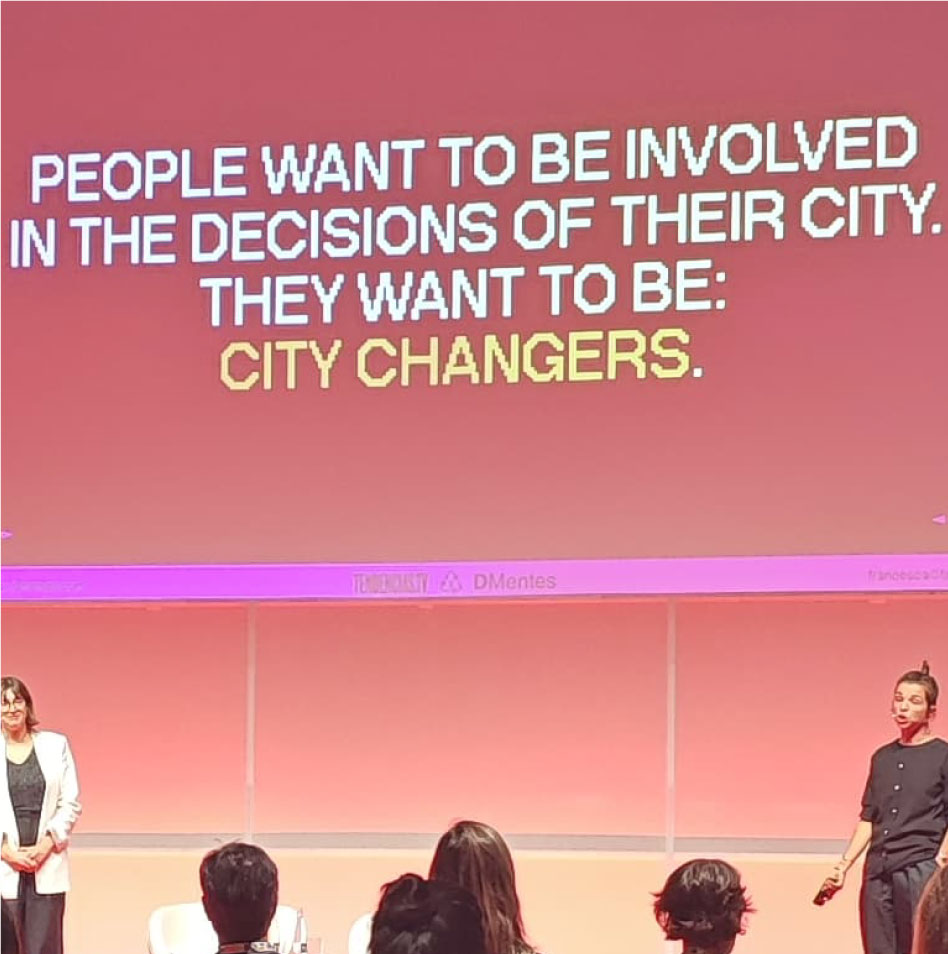

Public spaces, those shared realms where communities intersect and coexist, play a pivotal role in fostering diversity and promoting antiracism. These spaces serve as the common ground where individuals of various backgrounds, cultures, and identities come together. In public spaces, the lines that separate us based on ethnicity, race, or other characteristics begin to blur, as the shared experience of coexisting takes precedence.

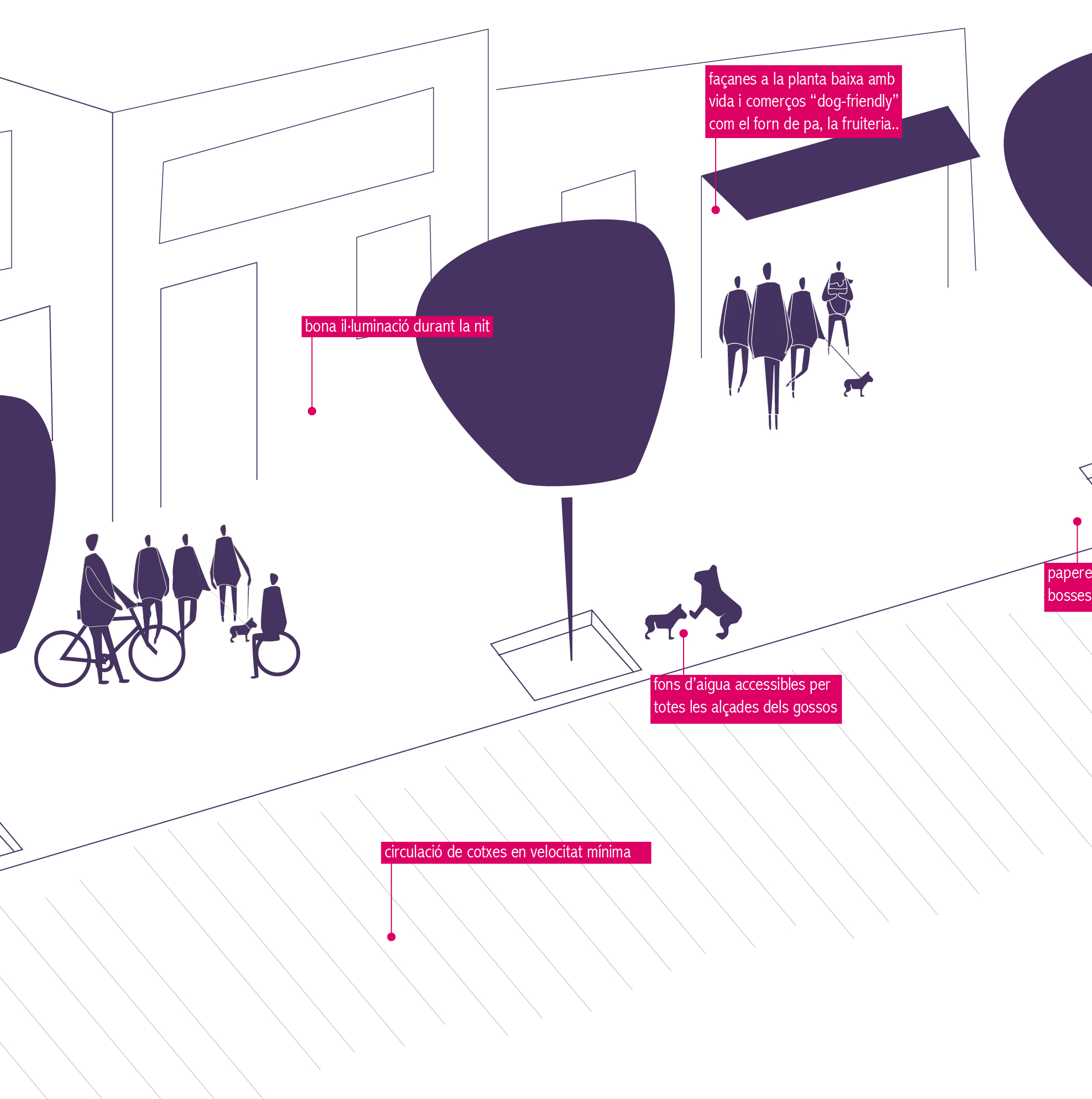

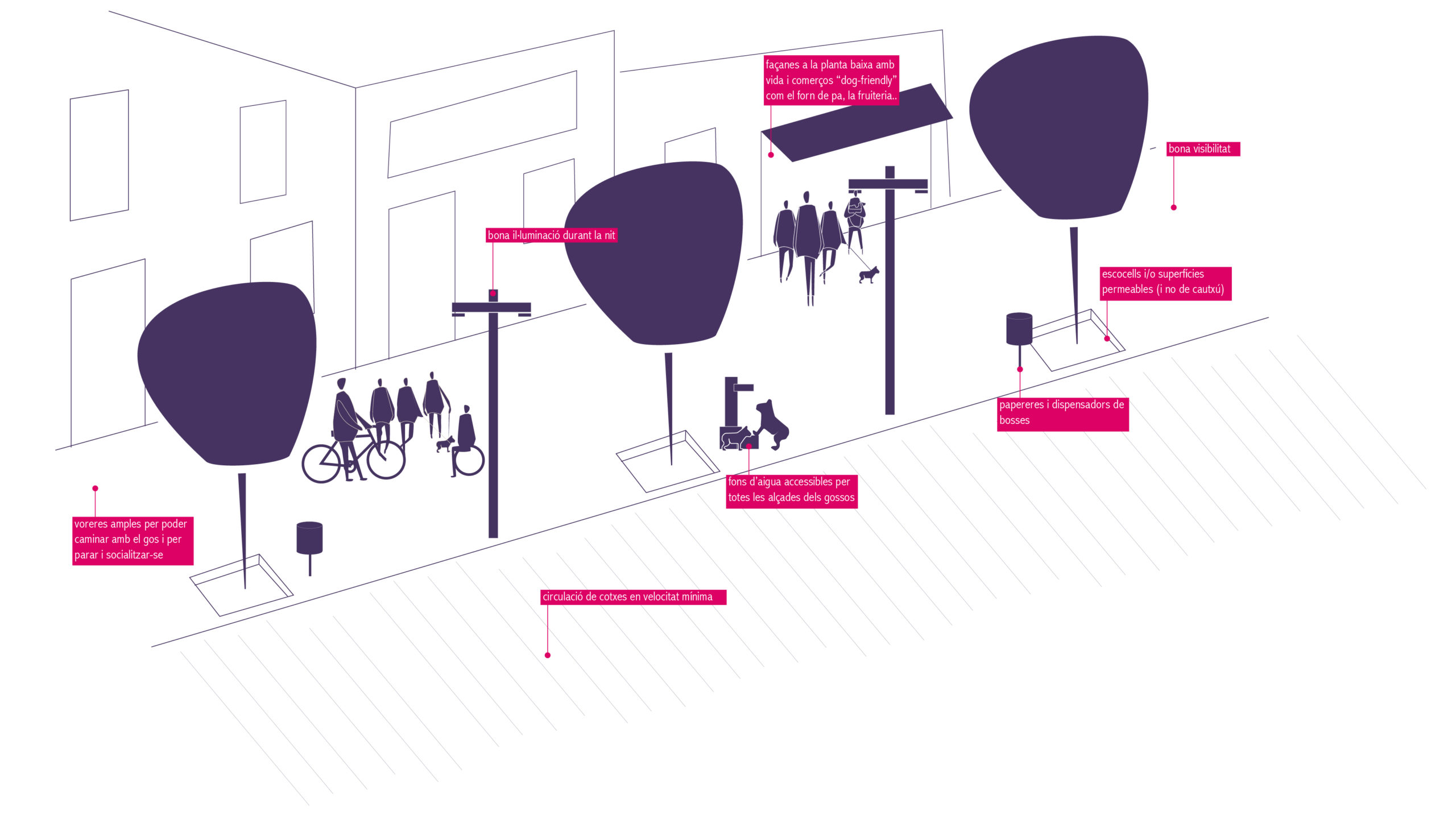

Jane Jacobs, in her timeless work “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” emphasizes the significance of well-designed urban areas. Cities have the potential to provide something for everybody, but only when they are created collaboratively. A harmonious city is characterized by clear boundaries between public and private spaces, with buildings oriented toward streets and sidewalks continuously bustling with activity. This inclusivity is the key to making cities vibrant and livable.

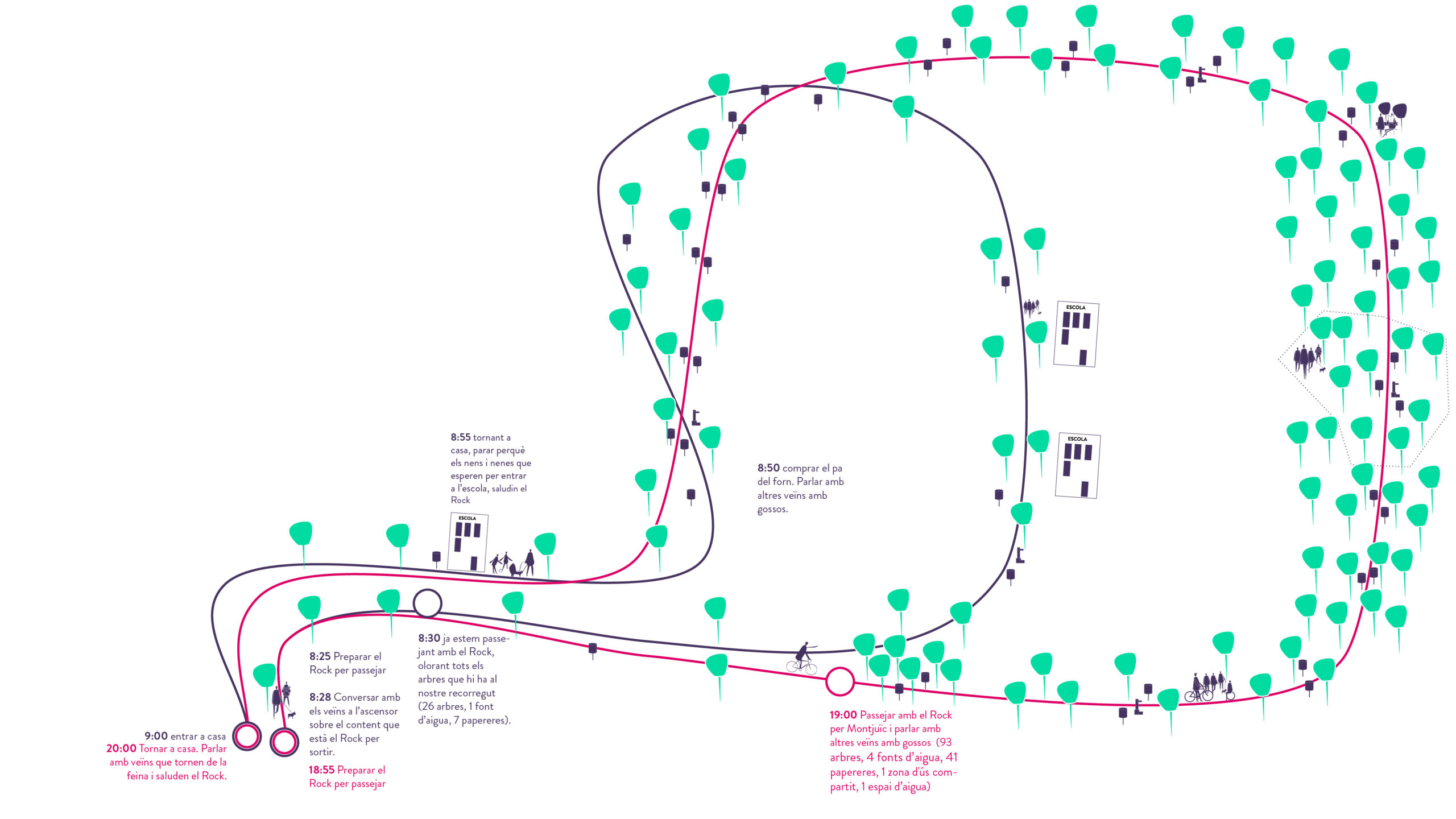

Public spaces, whether bustling city squares, serene parks, or vibrant neighborhoods, offer an opportunity for individuals to engage with one another. This engagement, often spontaneous and unscripted, allows people to witness the surrounding diversity, breaking down stereotypes and prejudices. The mere act of sharing a public space fosters a sense of interconnectedness, promoting empathy, understanding, and appreciation of different cultures and identities.

Moreover, these spaces provide a platform for the expression of diverse identities. Cultural events, festivals, and gatherings in public spaces celebrate a rich tapestry of traditions, languages, and customs. They become a testament to the beauty of diversity, showcasing the value of different perspectives and experiences.

In our quest to honor diversity and promote antiracism, public spaces offer a critical arena for change. Angela Y. Davis reminds us that in a racist society, it’s not enough to be non-racist; we must actively be anti-racist. This means challenging systemic prejudices and working towards a more inclusive society. In this process, the personal becomes political as we confront the ideologies that underlie racism and repression. The very design and utilization of public spaces can either perpetuate racial inequalities or challenge them.

By creating inclusive and accessible public spaces, we send a powerful message that all individuals, regardless of their ethnicity or race, have a right to exist, interact, and thrive in our communities. When public spaces are designed to accommodate a variety of cultural expressions, they contribute to dismantling systemic prejudices and fostering an environment of acceptance and equality.

“The Big Welcome,” an adaptation of words by Kate Morales, epitomizes the essence of public spaces in welcoming individuals of all backgrounds. It acknowledges their culture, ethnicity, religion, and gender, emphasizing that everyone is welcome, and their unique identities are celebrated.

Amin Maalouf’s idea of heritage highlights the role of culture in constructing a sense of belonging. People carry their heritage with them, whether in the form of names, languages, rituals, or memories. These portable emblems of the past lend continuity to new homes and serve as a connection to one’s roots.

Identity, deeply rooted in cultural memory, is maintained through collective self-images, rites, monuments, and institutional communication. Maurice Halbwachs’ concept of fixed points and figures of memory underlines the significance of cultural objectivation in preserving and stabilizing cultural memory.

In a rapidly changing world, our identities and the spaces we inhabit must reflect the richness of human diversity. Public spaces stand as the physical embodiment of our commitment to antiracism, where all individuals can embrace their identity and find their place in a world that values and celebrates the full spectrum of human experiences. As Maya Angelou wisely noted, “If we try and understand each other, we may even become friends.” It is this understanding and acceptance, fostered by public spaces, that will lead us toward a more harmonious and inclusive future.

* References

- Angelou, Maya. “Wouldn’t Take Nothing for My Journey Now.” Bantam, 1993

- Jacobs, Jane. “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.” Vintage, 1992.

- Davis, Angela Y. “Freedom is a Constant Struggle.” Haymarket Books, 2016.

- Maalouf, Amin. “In the Name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong.” Penguin, 2001.

- Morales, Kate. “The Big Welcome,” adapted from Mycelium School (2013-2016), in “Slow Spatial Reader: Chronicles of Radical Affection,” edited by Carolyn F. Strauss, Valiz, 2021.

- Lowenthal, David. “The Past is a Foreign Country.” Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Halbwachs, Maurice. “On Collective Memory.” University of Chicago Press, 1992.

- Wilhelm Reich, “Listen, Little Man!”, The Noonday Press, 1948

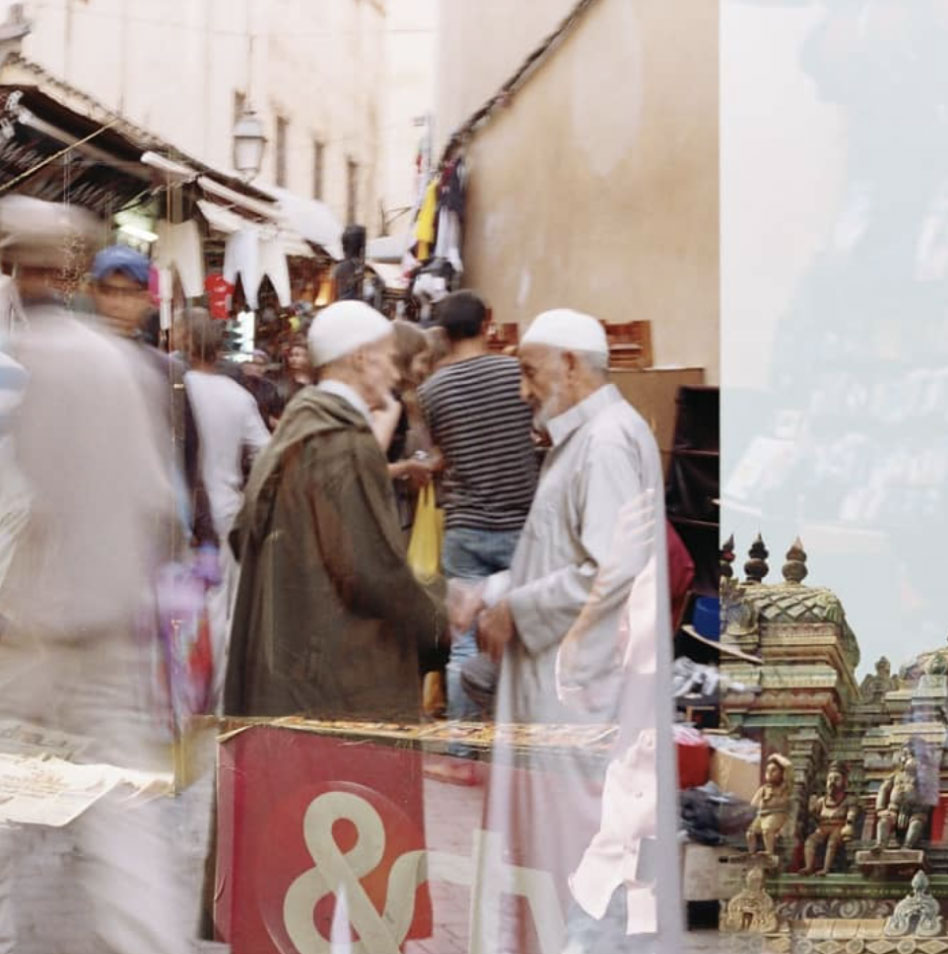

Photo: Konstantina Chrysostomou, 2016

Words of:

Konstantina Chrysostomou

Publication date:

13/10/2023

Originally written in:

english

Tags:

Everyday life / Public space