The soul of the city

Festivals in public space

“A part of what has characterized life in European cities has taken place in their open public spaces. The public space has not been the negative space of homes but the positive space of the city. Public space has emerged, it has been created to be the place of assembly, the market, the celebration, justice, theater, work, play, encounter, conversation, religion, carnival, music…” – Jan Gehl

Public space, as noted by Jan Gehl, has been the backdrop of a rich and diverse urban life over the centuries. It has been a place where the community gathers, celebrates, and becomes part of the city’s history. In this ode to public space, we will explore the importance of using this space for celebrations and festivals, with a particular focus on how these events shape public space and transform it into a living platform for culture, diversity, and collective identity.

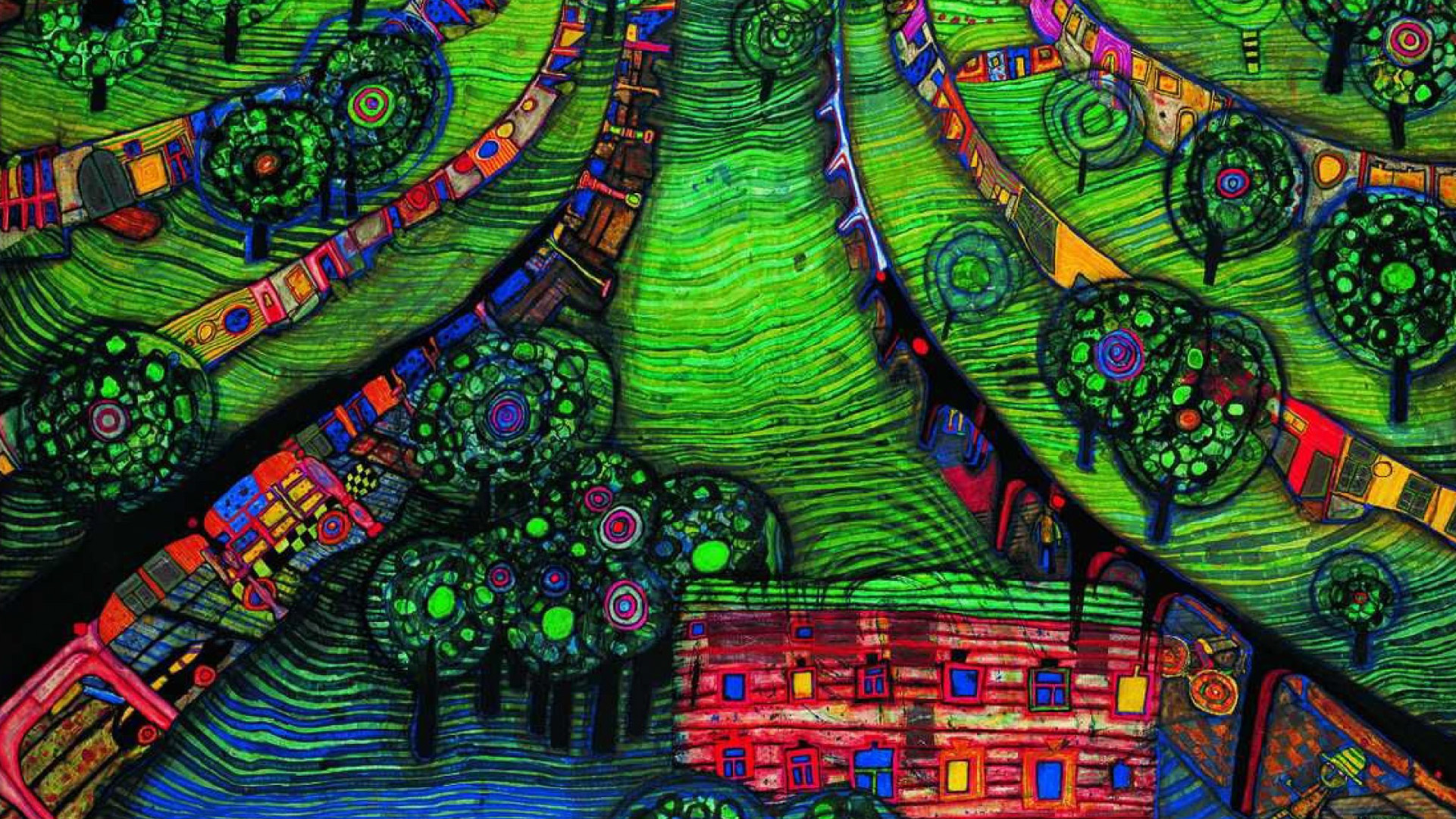

Public space is more than urban infrastructure; it is a place where life takes shape and experiences are shared. Festivals in public space enrich the city and breathe life into the collective imagination. These celebrations not only configure the physical space but also endow it with new meaning, utilizing the opportunities it provides.

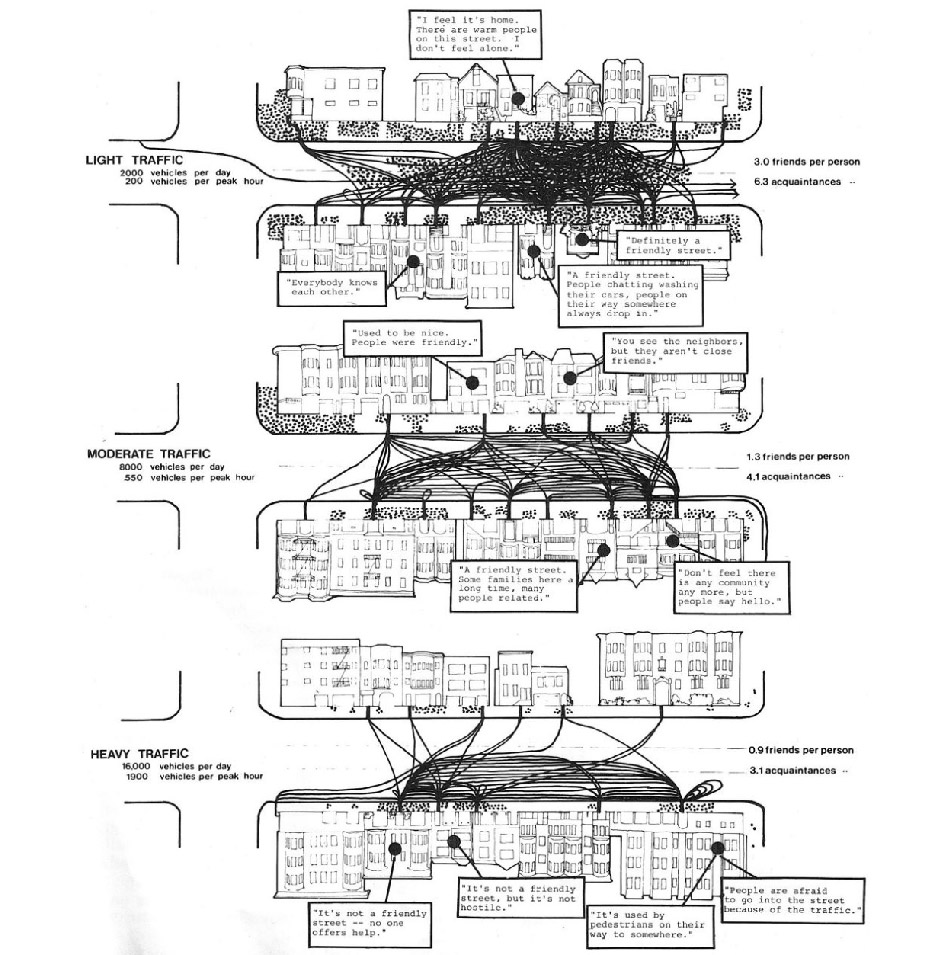

Events held in public space become true manifestations of gathering and community. People from all corners of the city converge there, turning strangers into friends in this festive and celebratory atmosphere. This meeting promotes community cohesion and fosters social interaction, as participants share a sense of unity and belonging to a common space. Festivals in public space are not isolated events but become points of encounter and connection between neighbors and visitors, weaving a community network that unites people from different backgrounds.

Furthermore, these events also serve as vehicles for culture and tradition. Many festivals celebrated in public space are inherently linked to local culture and traditions. From musical performances to traditional attire and specific rituals, these celebrations help preserve and transmit the rich cultural heritage of the community. Through music, dance, performances, and other cultural elements, the identity and roots of the community are highlighted, allowing these traditions to continue to thrive through the generations.

Diversity and inclusion are also fundamental values that are evident in public space celebrations. These celebrations offer an opportunity for people of all kinds, regardless of their ethnic background, religion, social class, or other characteristics, to celebrate together. Public space becomes a place where differences fade away, and people come together to enjoy a prejudice-free and barrier-free celebration environment. This dimension of inclusion and diversity promotes a deeper and more respectful understanding of different cultures and encourages peaceful coexistence and the acceptance of diversity within society.

Examples of Public Space Festivities

Carnival in Brazil

Public space becomes crucial for the Carnival celebrations in Brazil, as it is the main stage where this celebration comes to life and significance. Carnival is a rich cultural manifestation deeply rooted in the country’s history, with its origins in the colonial era and the interaction between indigenous, African, and European cultures. In this sense, public space becomes the area of maximum expression of this cultural and religious diversity.

Author Emanuelle Kierulff explores how different samba schools occupy and define public spaces through their parades and celebrations, thus shaping the urban and territorial space of different neighborhoods. The samba school parades become true public spectacles that use the main streets of the cities, emphasizing and reclaiming these spaces as venues for cultural expression. Furthermore, Carnival street parties are the setting where the city’s inhabitants can participate in and experience this cultural expression as direct actors.

In this sense, public space is not merely a backdrop for Carnival celebrations; it becomes an active protagonist that shapes the cultural identity of local communities. This transformation of public space into a place of celebration, encounter, and cultural expression is essential for the continuity and evolution of this important Brazilian festival, highlighting the importance of public space as a stage and cultural mediator in celebrations worldwide.

Las Fallas in Valencia

Las Fallas in Valencia is an iconic and emblematic celebration that highlights the importance of public space in the city’s life and culture. This festival, with its ephemeral artistic monuments and fireworks shows, unfolds in every corner of Valencia, turning public space into a collective stage where cultural and social communion takes place. The streets, squares, and small plazas become meeting places where Valencians and visitors come together to enjoy this unique celebration.

The Fallas festival, with its deep roots and strong connections to Valencia’s history, serves as a paradigmatic example of how public space becomes a stage for cultural and social expression. This is where art, tradition, and creativity are manifested, as local and foreign artists work to build the magnificent monuments that will be burned in a spectacular fire ceremony after a few days. Public space in Valencia comes to life with cultural events during this festival, and Las Fallas would not be what they are without their intrinsic relationship with the city’s streets and squares.

Patum in Berga, Catalonia

Public space plays a fundamental role in the celebration of the Patum de Berga, a traditional and ancient festival declared Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. The Plaza de San Pedro and other streets and squares in Berga become the main stage where this festival comes to life. As mentioned by Richard Sennett, public space is the stage for the festival, the place where the community gathers to celebrate its cultural roots. The layout and configuration of Berga’s public space allow the different “collas” or groups participating in the Patum to perform their traditional acts and dances with precision and spectacle. Public space becomes the soul of the festival, where social interaction and connection with local culture are possible. This celebration is a vivid example of how public space can be a platform for the preservation and transmission of cultural traditions, connecting people with their history and the roots of their past.

Holi, India

Public space in India plays a crucial role in the celebration of Holi, the festival of colors that is one of the country’s most iconic celebrations. Holi is a commemoration of spring and the victory of good over evil. The streets and squares of cities and towns become the main stage for this festival, where people gather to throw vibrant colored powders, dance, sing, and share joy.

Public space becomes a meeting place and a focal point for the community during Holi, where social and economic differences disappear, and people of all backgrounds can participate in the celebration. This festive event promotes community cohesion and offers the opportunity to promote India’s own culture and traditions, contributing to their continuity and enrichment.

The use of public space during Holi reflects the deep-rooted nature of this festival in the everyday lives of people in India. Additionally, public space becomes a witness to the diversity and inclusion that characterize this celebration, as people from different backgrounds come together to enjoy a festival that celebrates life, fertility, and unity. It is in India’s public space that Holi comes to full fruition and becomes a living manifestation of the country’s culture and identity.

Qualities of Public Space

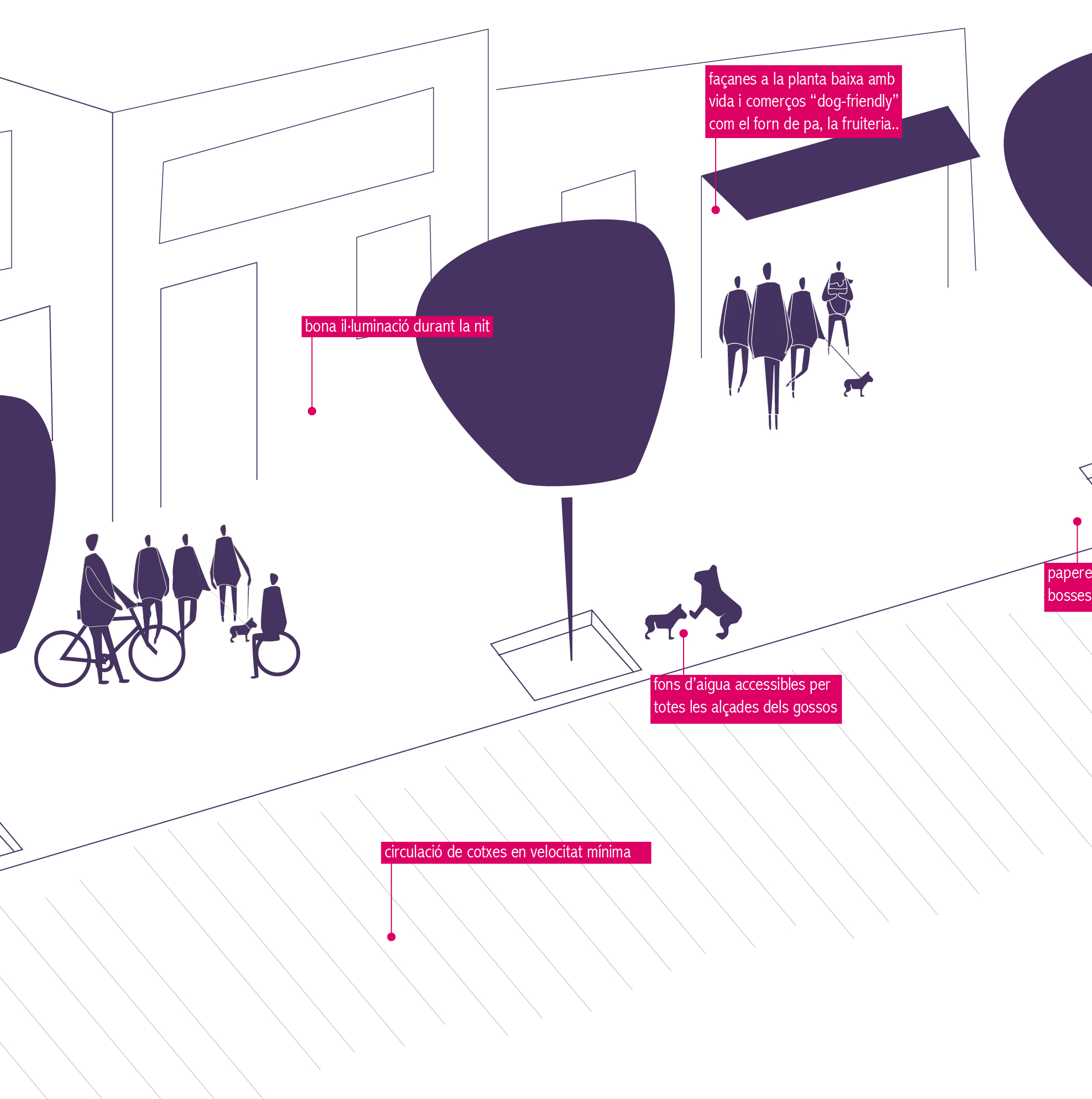

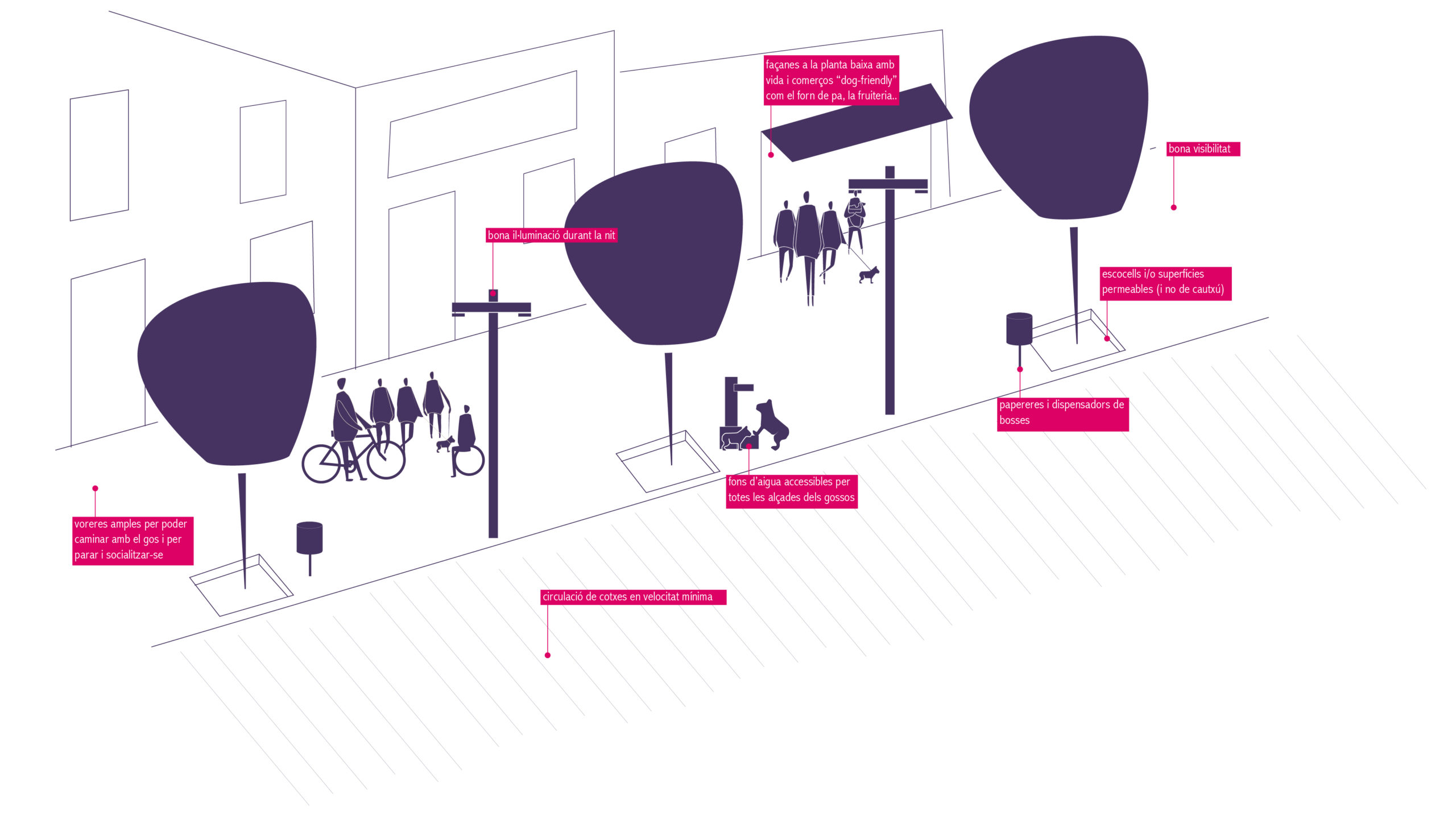

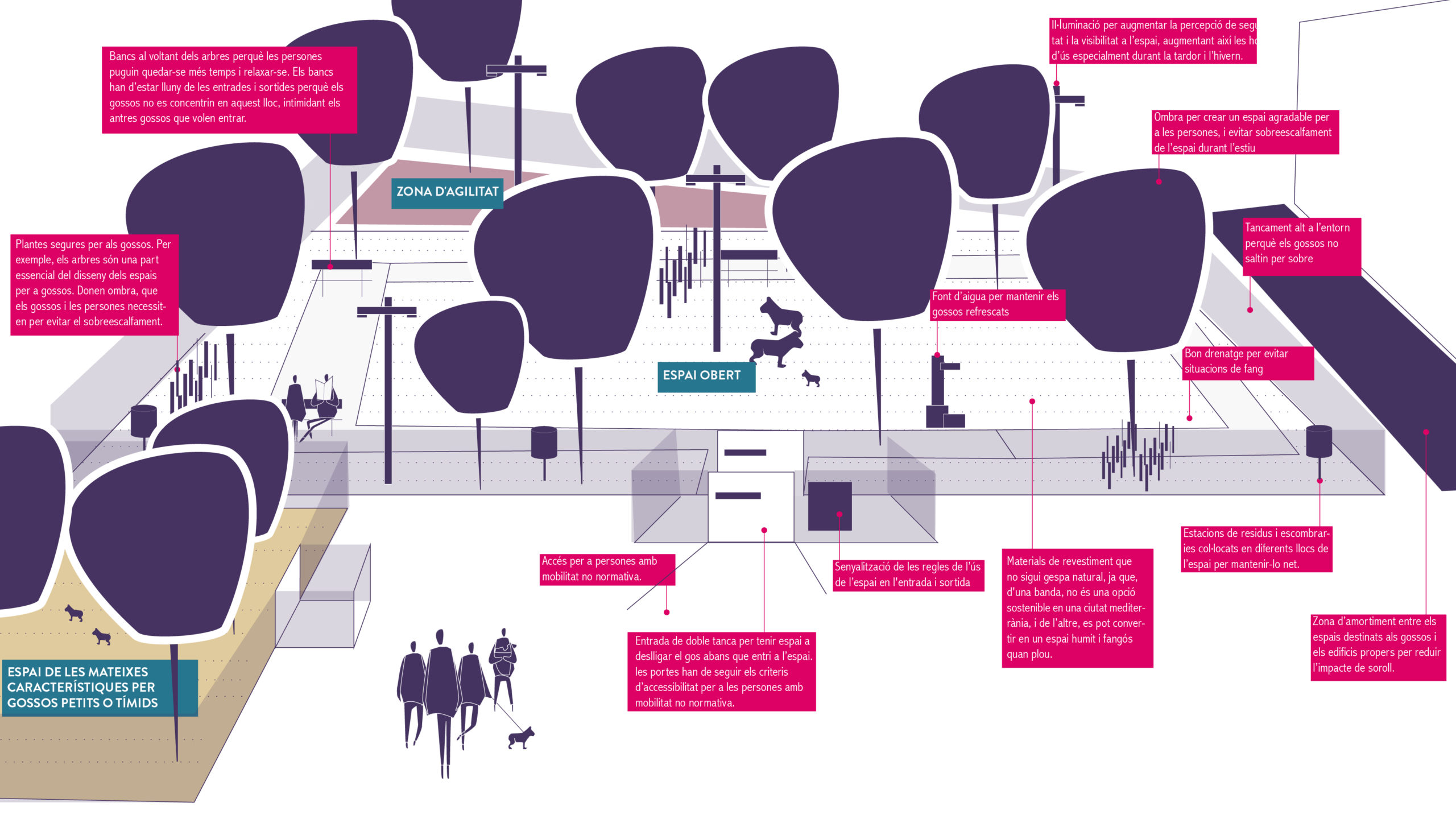

Therefore, a good public space for hosting festivities or celebrations worldwide must meet several important requirements. The key elements necessary include:

- Spaciousness and Accessibility: The space must be large enough to accommodate festivities and should be accessible to people with reduced mobility, with clear access and exit routes for emergencies.

- Platforms or Stages: Temporary platforms or stages are often needed for participants to carry out their performances.

- Adequate Lighting: If the event takes place at night, it is essential that the space has proper lighting to ensure safety and visibility.

- Information and Assistance Points: Establish information and assistance points with qualified personnel focused on addressing emergency situations or assisting individuals who may feel insecure. These points can provide information on how to navigate the event safely and serve as locations to collect incident reports.

- Spectator Areas: The public space must have designated areas where spectators can safely watch the performances without interfering with the participants.

- Basic Services: Facilities such as public restrooms, water points, and emergency services (such as medical personnel and security personnel) should be available to all participants.

- Safe Design: The space should be designed to ensure the safety of participants and spectators. This may include safety barriers, signage, and controlled access.

- Cleaning and Waste Collection: Authorities should coordinate cleaning and waste collection services to ensure that the public space remains clean and safe during and after the event.

- Public Transportation Accessibility: A good public space should be easily accessible via public transportation to facilitate the participation of people from outside the area.

Public space festivities are living witnesses to culture, tradition, and diversity. These events not only configure the physical space but also transform it into a platform for community cohesion and inclusion. Celebrations such as the Rio Carnival, the Fallas of Valencia, the Patum of Berga, and Holi in India demonstrate how public space can be a place of gathering and celebration where diversity is celebrated. These festivals make public space come alive, changing and becoming essential for city life, and reminding everyone that the streets are not just for traffic but for community and culture.

* References

- Ferri, L. (2007). Las Fallas de Valencia. Un análisis desde la perspectiva urbana. Cuadernos de estudios urbanos y regionales, 8(19), 97-118.

- Porcar, A. M. (2014). Las Fallas de Valencia y el patrimonio cultural. Apuntes desde la antropología urbana. Revista d’etnologia de Catalunya, (39), 26-35.

- Richard Sennett, “The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life.”

- Patum de Berga, “Declaració de la Patum com a Patrimoni Cultural Immaterial de la Humanitat per la UNESCO.”

Words of:

Konstantina Chrysostomou

Publication date:

13/10/2023

Originally written in:

Catalan

Tags:

Everyday life / Public space