Protecting Democracy Through Participatory Democracy and Social Movements

Democracy is often reduced to the act of voting: electing representatives to speak on behalf of the people and waiting until the next election cycle to make our voices heard again. However, democracy in its truest form must extend far beyond the ballot box. It requires the active participation of citizens in decision-making processes and must be rooted in the everyday experiences and struggles of the people. Social movements, in particular, have historically played a vital role in expanding the democratic process and ensuring that it remains alive, dynamic, and inclusive.

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the Biennale de Pensament in Barcelona, where I listened to thought-provoking discussions on the importance of protecting democracy and the role of participatory democracy in this endeavor. Speakers like Donatella Della Porta, Amador Fernández-Savater, and Claudia Delso Carreira provided powerful insights into how we can strengthen democratic processes by fostering greater citizen involvement and collective action. Their reflections reinforced the idea that participatory democracy is not just a theoretical concept but a practical necessity in the face of growing threats to democratic systems worldwide.

The Limits of Representative Democracy

Representative democracy, though an essential pillar of modern governance, is often insufficient in addressing the complexities and inequalities that exist within society. Elections can too easily become disconnected from the realities of marginalized groups—whether due to gender, class, race, or sexual orientation. Social movements, on the other hand, bring these marginalized voices to the forefront. As one speaker points out, “There are many power dynamics that humiliate certain bodies,” highlighting how systemic oppression targets particular groups. Traditional democratic structures may overlook these issues, but social movements create spaces where those who have been silenced can be heard.

Participatory democracy offers a framework for transforming these frustrations into action. It is not merely about voting once every few years but about engaging directly with the issues that matter most to the people. It is about dialogue, collective problem-solving, and forming alliances across diverse sectors of society. This process of “inventing an identity and forming alliances with people different from you” reflects a more profound democratic engagement—one that allows for the development of a more inclusive society.

The Role of Social Movements in Expanding Democracy

Social movements have always been at the heart of democratic transformation. From labor rights to women’s suffrage, from civil rights to environmental justice, movements are born out of the need to address injustices and bring about change. These movements do more than just demand reforms; they challenge the very structures that perpetuate inequality and offer alternative visions of governance and community.

In recent years, movements such as the Tenants’ Union and grassroots initiatives around the world have demonstrated the power of collective action. One significant example comes from Bolivia, where a community-driven museum challenges colonial narratives by involving indigenous communities as co-authors of the museum’s exhibits. This participatory approach disrupts traditional power dynamics and reshapes the way knowledge is produced and shared. As one observer noted, “We must learn to listen with respect, observe, and change established practices that perpetuate domination.”

By pushing beyond the established limits of representative democracy, social movements remind us that democracy is not static. It must be continuously worked on and protected. These movements have the potential to reshape public spaces, create more equitable institutions, and engage citizens in meaningful ways. They serve as vital incubators for democratic innovation and hold power to account when traditional political structures fall short.

Participatory Democracy as an Antidote to the Market-Driven System

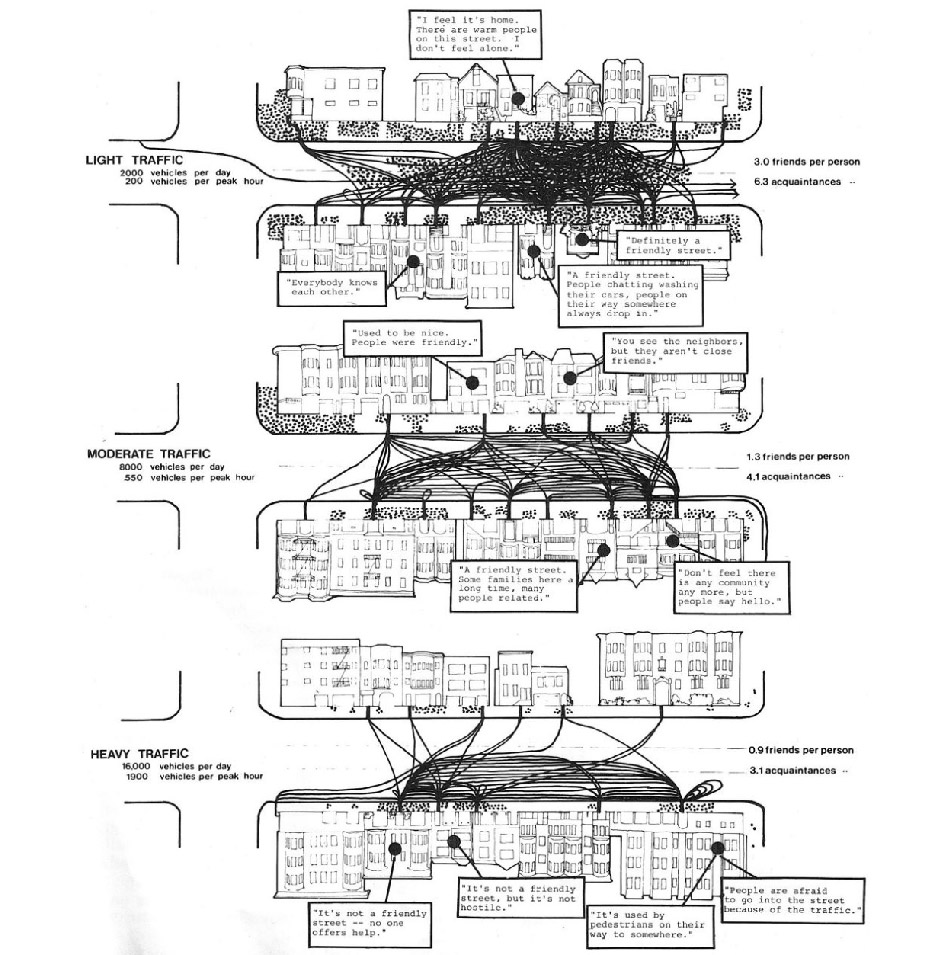

One of the primary challenges facing democracy today is the increasing influence of neoliberal market forces that prioritize profit over people. The dominance of the market system has seeped into every aspect of life, including democratic institutions, turning citizens into consumers rather than active participants. In response, social movements and participatory democracy offer a pathway to reclaim public space from the grips of market logic.

As another commentator pointed out, we are living in a time when “market life fosters selfish behavior,” but our very nature as human beings is built on cooperation. Participatory democracy, when practiced fully, brings people together in a shared space where cooperation, not competition, becomes the guiding principle.

In this light, democracy is not just a tool for governance but a space for building community and solidarity. It provides an alternative to the neoliberal notion of individualism, emphasizing instead collective well-being. The idea that “our cells are designed to cooperate” challenges the belief that democracy must be structured around competition and power struggles. Participatory democracy calls for inclusiveness, deliberation, and shared responsibility for the collective good.

Protecting Democracy in the Face of Reactionary Politics

The rise of far-right movements and populist leaders worldwide represents a significant threat to democracy. These reactionary forces often appeal to people’s fears, manipulating them with misinformation and xenophobia. Social movements, however, can act as a counterforce by promoting informed and empathetic dialogue. The growth of movements that challenge corporate dominance in education, healthcare, and housing demonstrates that citizens are not willing to passively accept these threats to their well-being.

But for these movements to be effective, they must move beyond mere criticism of the system. Critique is important, but as one scholar notes, “Criticism is a way of not wanting anything to change.” Instead of simply pointing out what is wrong, movements must focus on building something better—creating spaces where people can come together to imagine and construct new futures.

It is crucial that social movements continue to expand the meaning of democracy beyond its institutional limitations. Democracy should not be confined to voting once every few years or limited to the decisions of a few elected officials. True democracy requires ongoing engagement and the protection of spaces where citizens can collaborate, challenge power, and work toward a common good.

The Future of Democracy: Building a Collective Project

The challenges facing democracy today are immense, but so are the opportunities. As social movements around the world continue to mobilize, they are showing that democracy can be more than a set of procedures or institutions—it can be a vibrant, participatory process rooted in the everyday lives of citizens.

Building on the lessons from past and present movements, we must continue to expand the scope of democracy, ensuring that it becomes more inclusive, equitable, and responsive to the needs of all people. As one speaker said, “Transformation is not just about the content, but about the ways of doing things.” We must rethink how we practice democracy, and this begins with embracing participatory methods that empower citizens to take an active role in shaping the world around them.

In conclusion, protecting democracy requires more than safeguarding elections or political institutions—it demands fostering a culture of participation, where diverse voices can come together, share their stories, and build new forms of solidarity. Social movements will continue to be the engine driving this transformation, and through them, we can build a democracy that truly works for everyone.

Quotes:

- “Cooperation is not just a tool of resistance, but a fundamental part of our human nature; it is how we have overcome adversity over time.”

- “Transformation is not just about content, but about the ways of doing things.”

- “We must learn to listen with respect, observe, and change established practices that perpetuate domination.”

- “Criticism is a way of not wanting anything to change. The real challenge is to build spaces where we can imagine and create better futures.”

- “Market life fosters selfishness, but our human nature is designed for cooperation.”

In a world where democracy faces constant threats, social movements and participatory democracy remain vital in keeping it alive and meaningful.

Words of:

Konstantina Chrysostomou

Publication date:

14/10/2024

Originally written in:

english

Tags:

Everyday life / Public space