Rescuing the Rambles of Barcelona

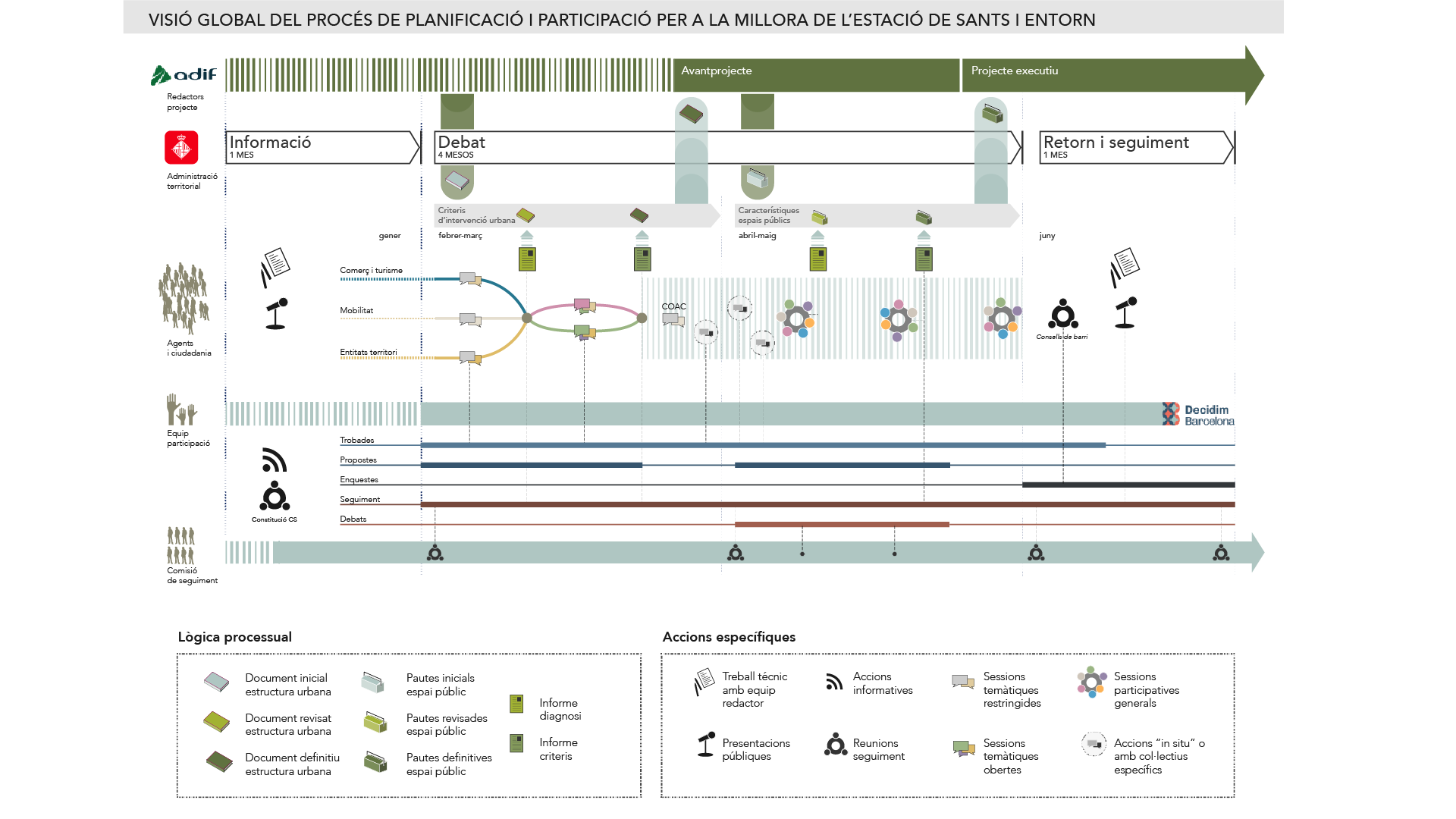

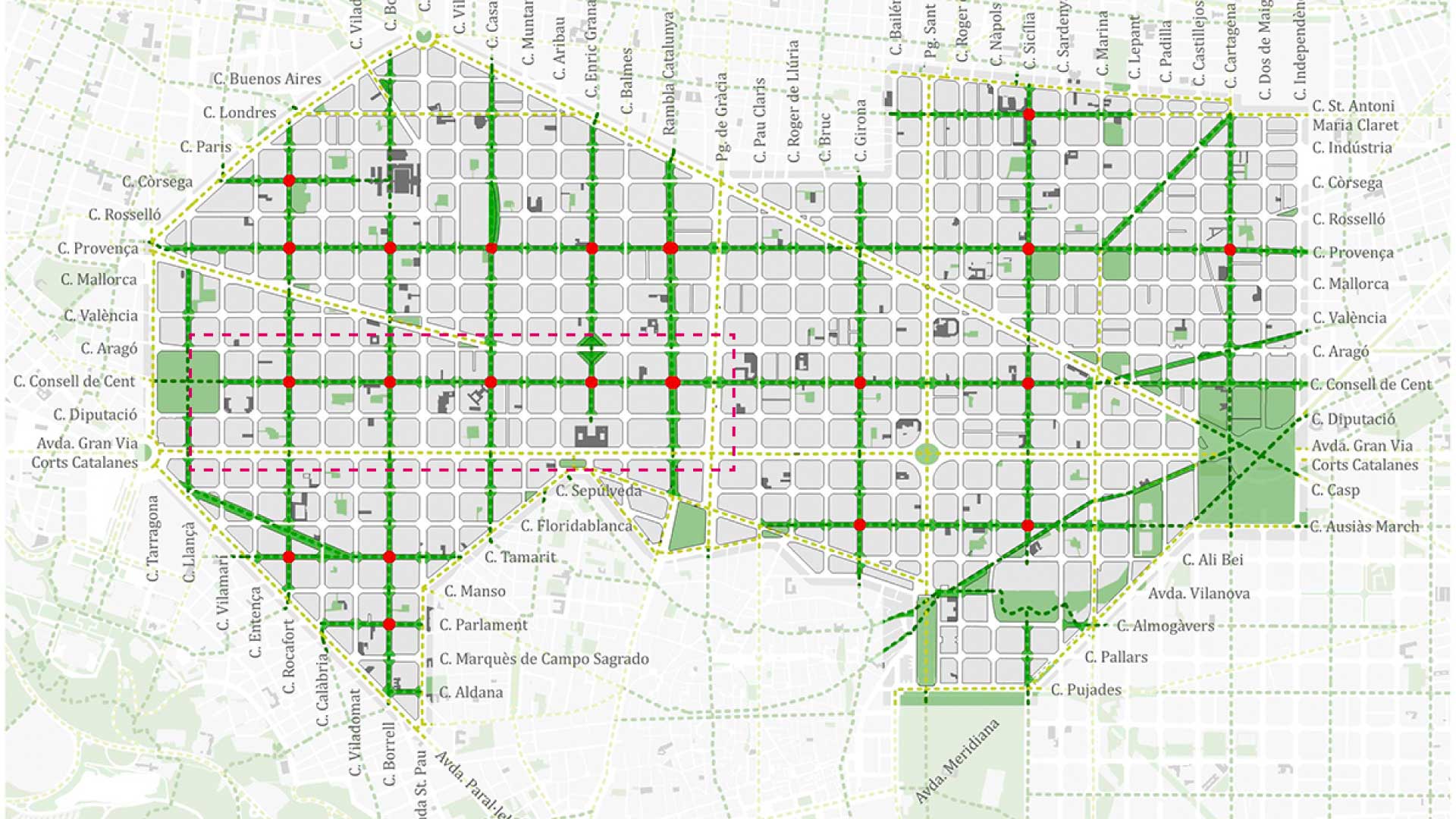

Les Rambles’ cooperative process was a proposal of the kmZero team that won the International Competition convened by the Barcelona City Council in 2017 to revitalize and remodel the Rambla de Barcelona. The aim is to return to the citizenry one of its historical and most symbolic axes in a cooperative way, so this transformation becomes, on the one hand, a global improvement of the city’s main urban space and on the other, a better experience for the people who live, visit and enjoy it.

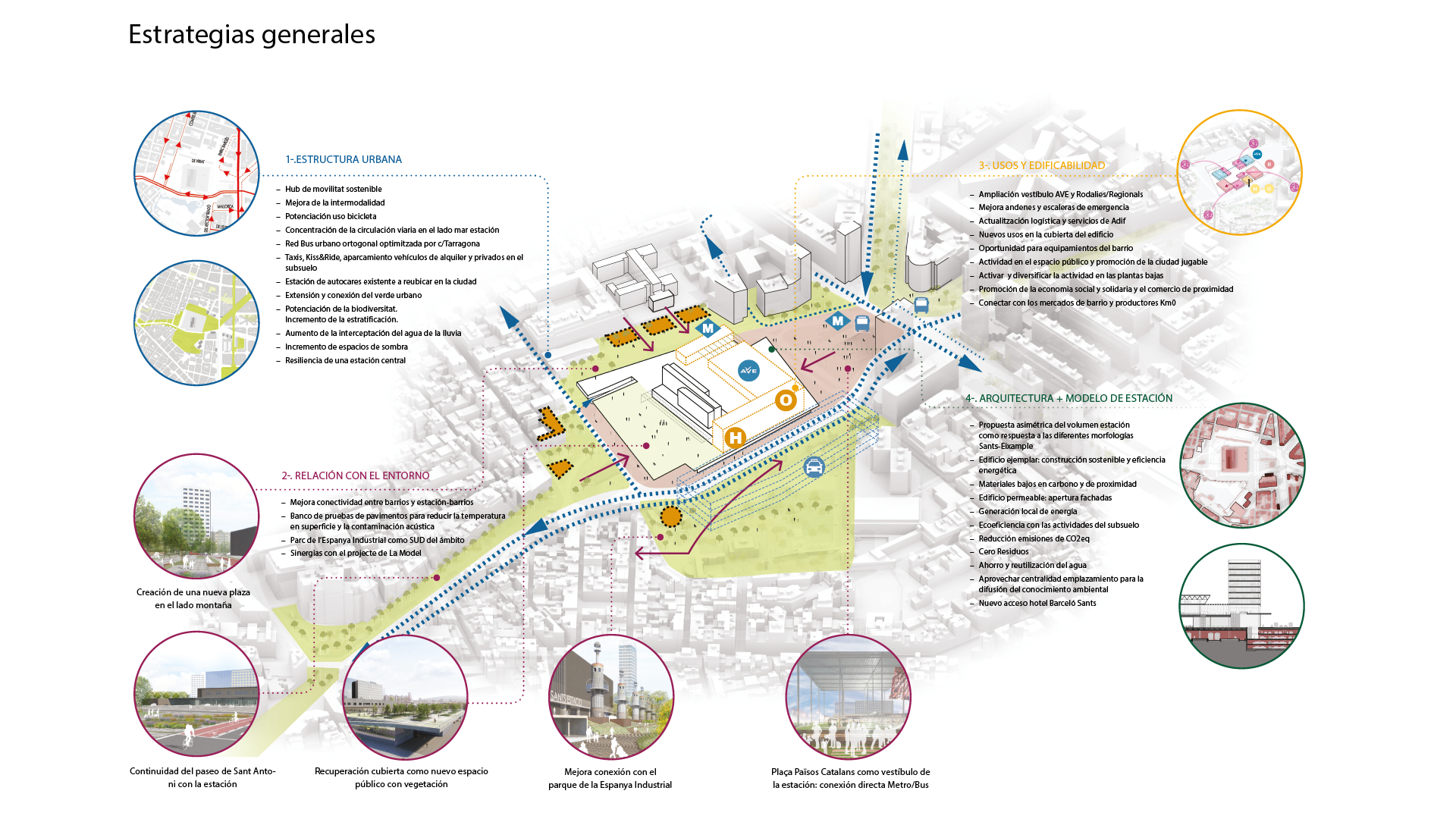

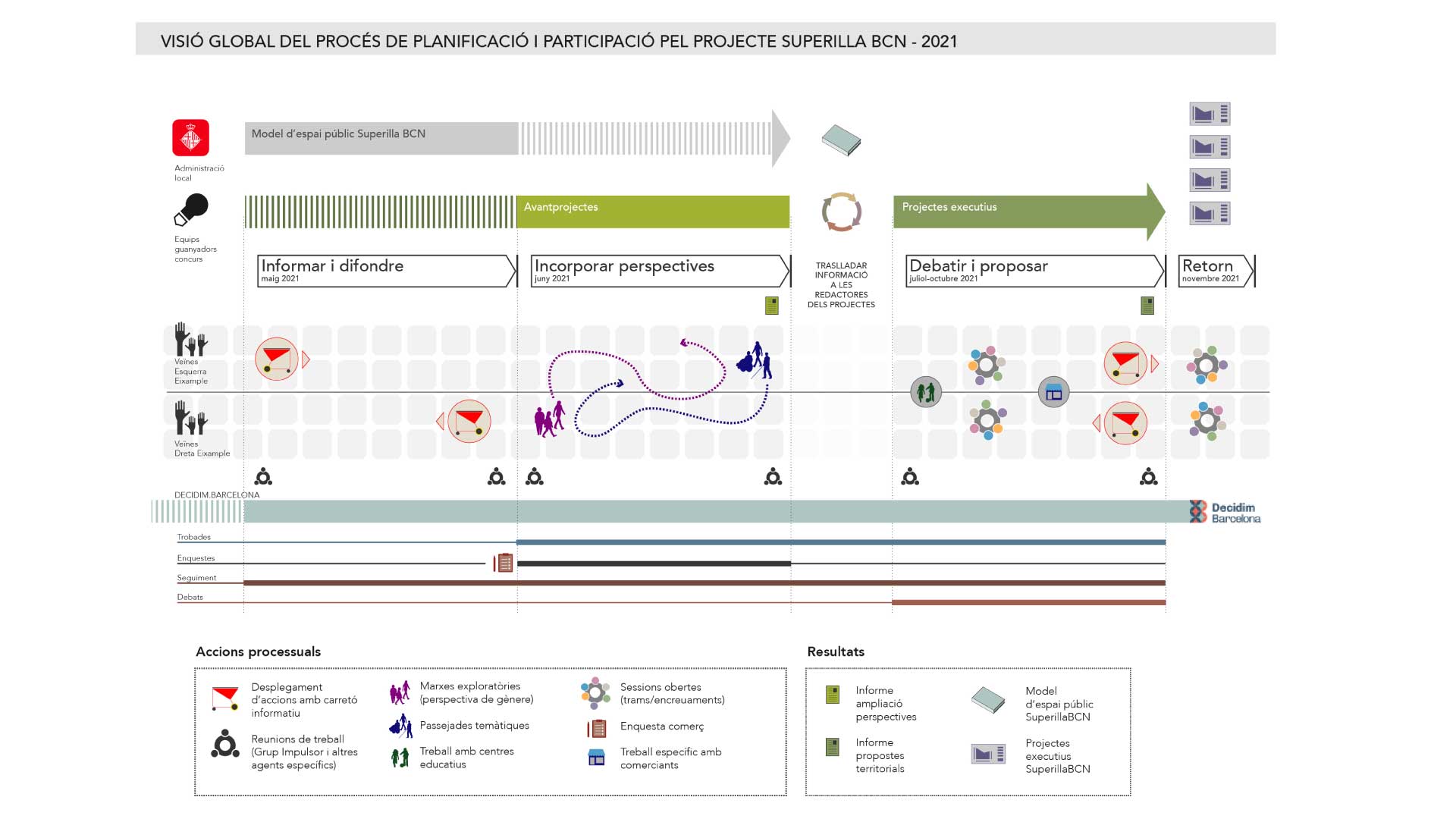

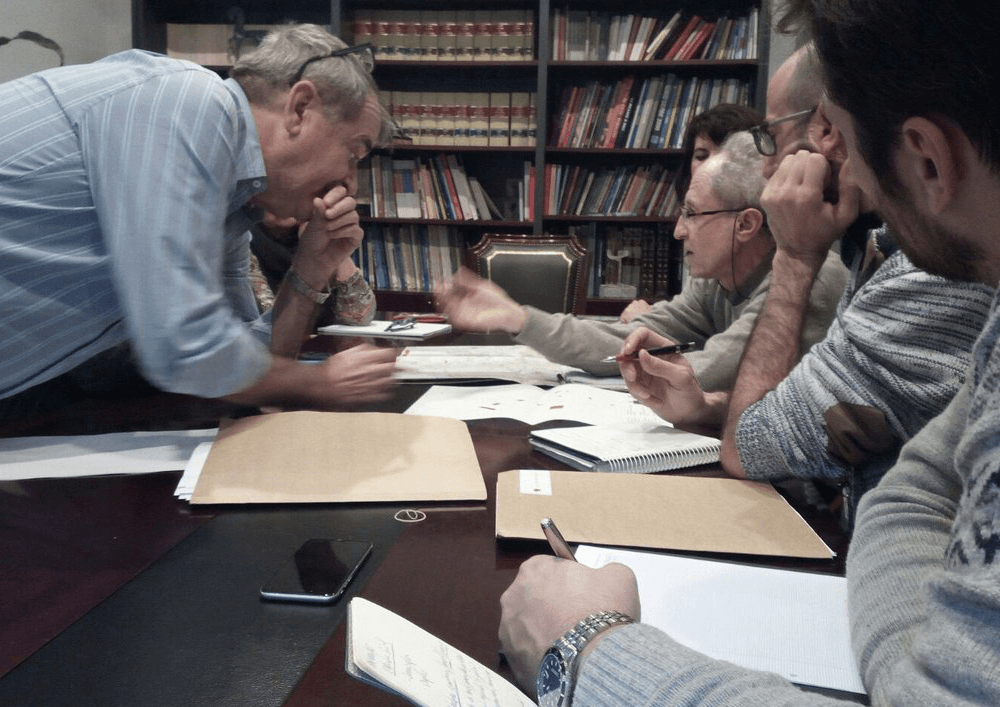

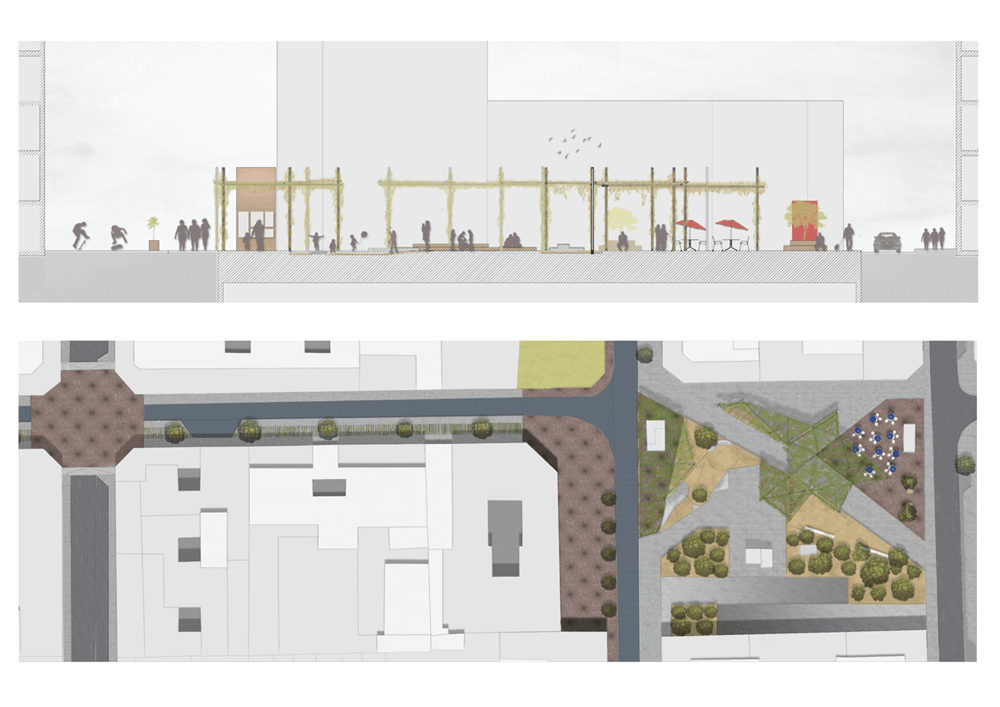

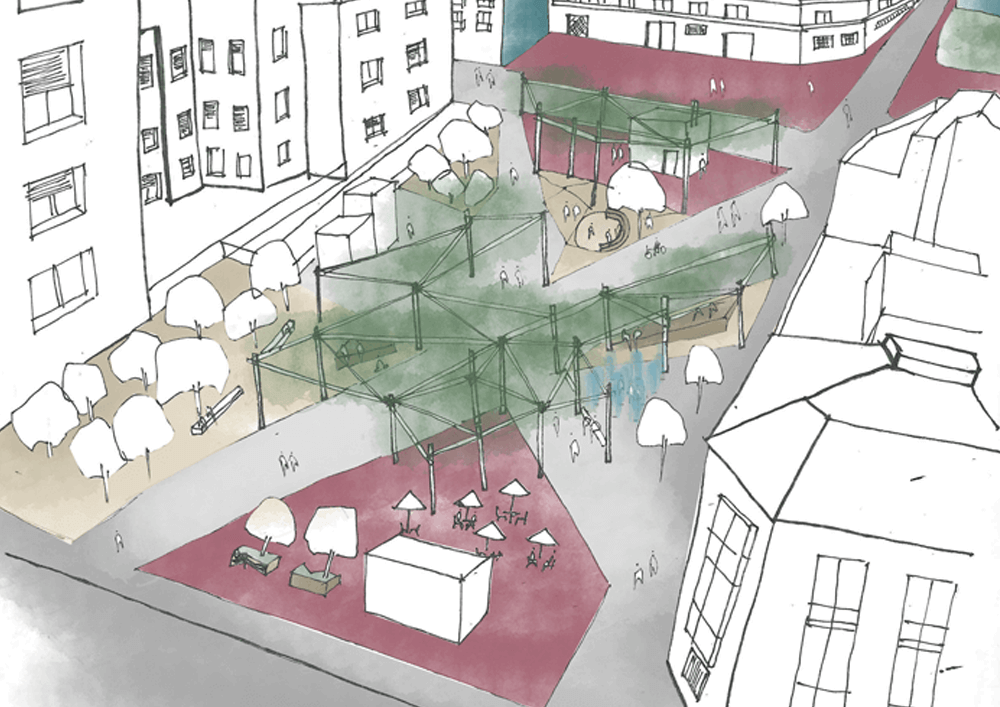

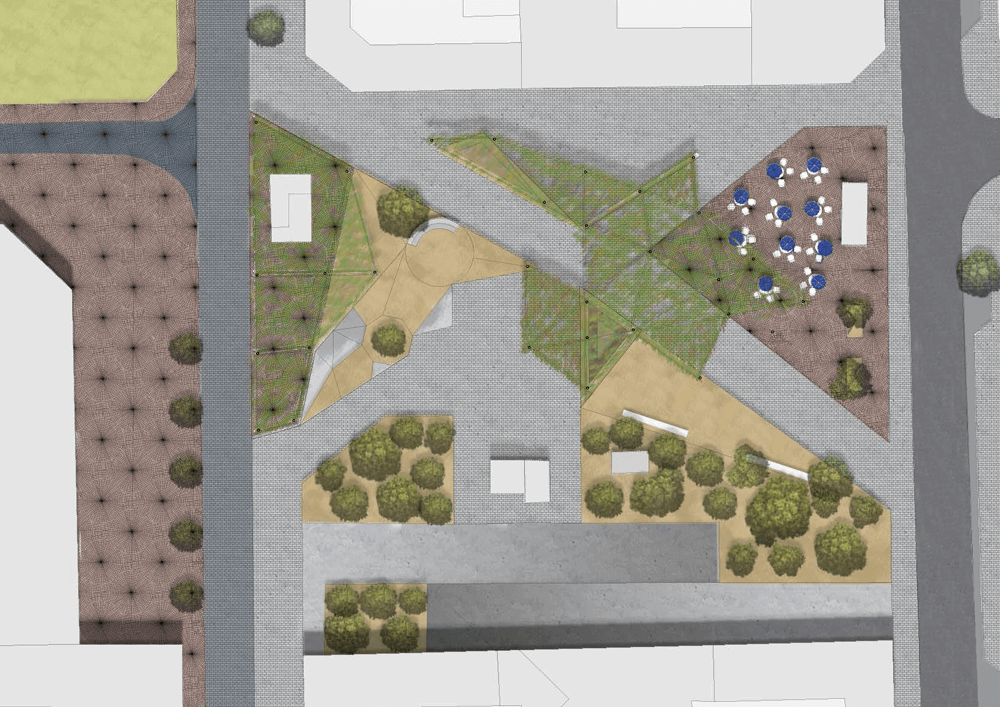

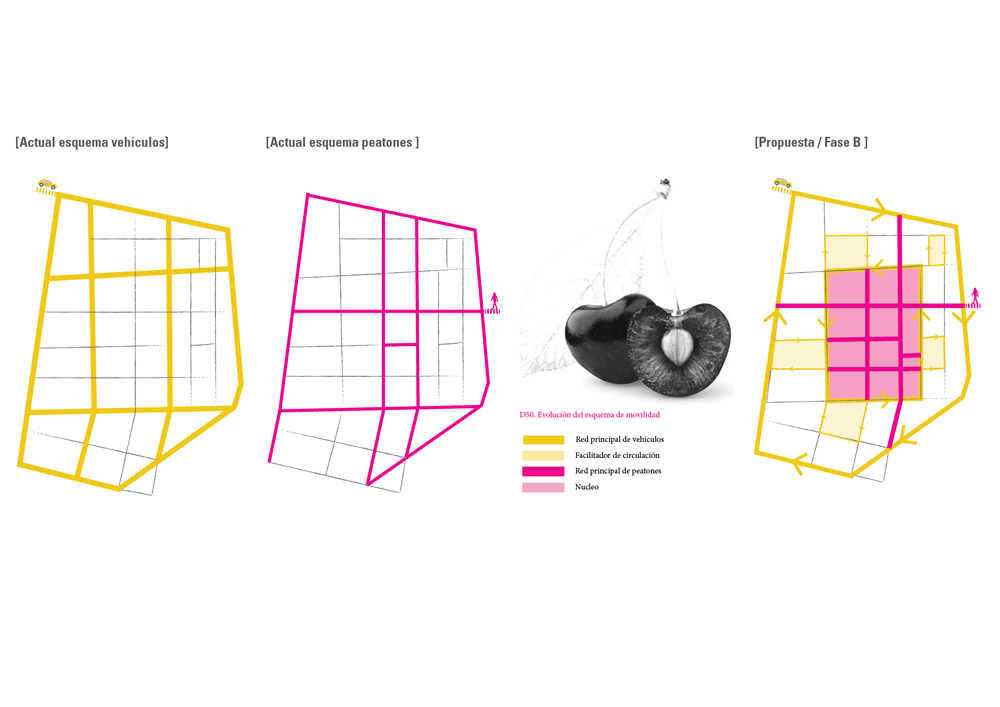

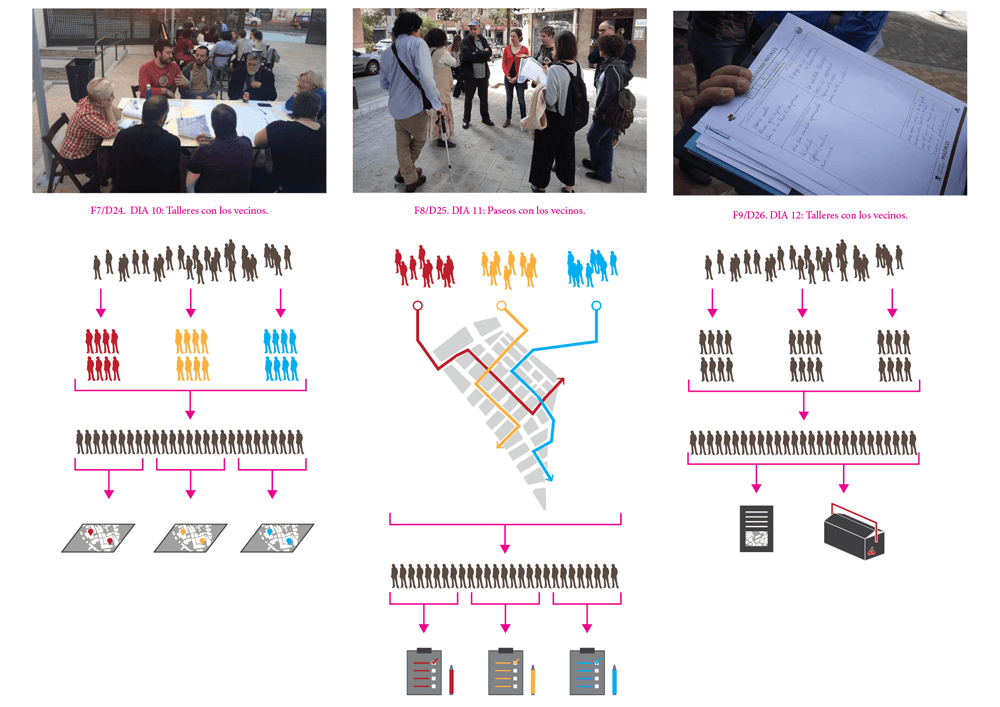

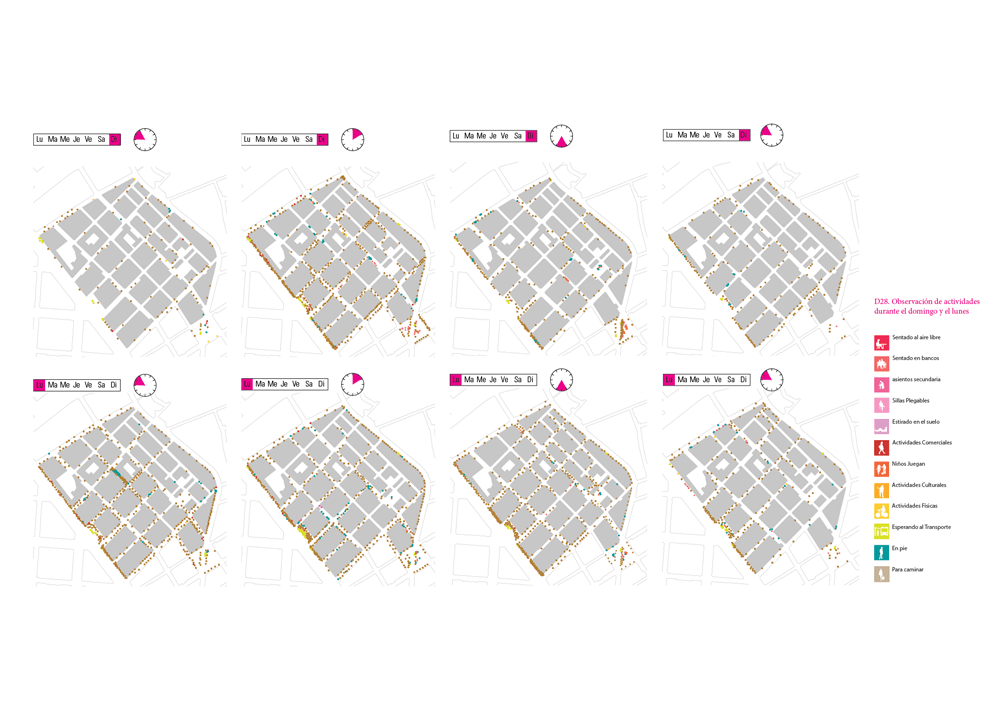

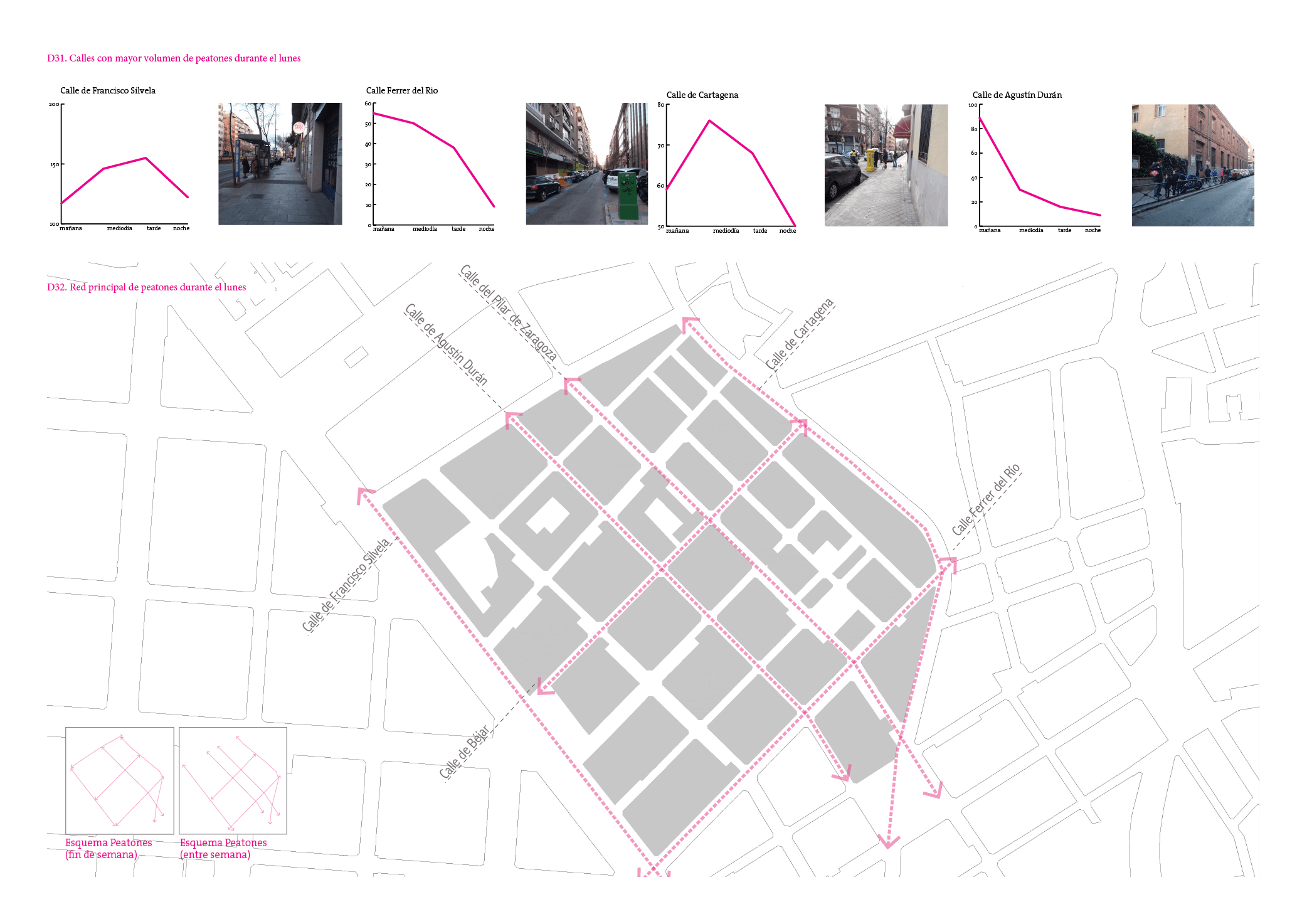

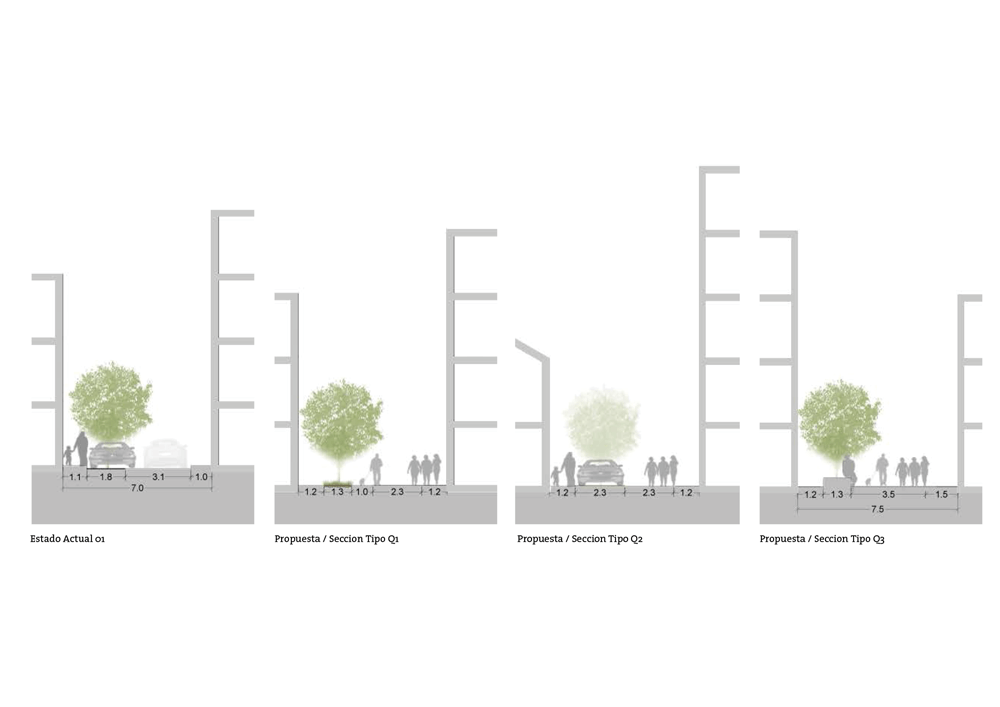

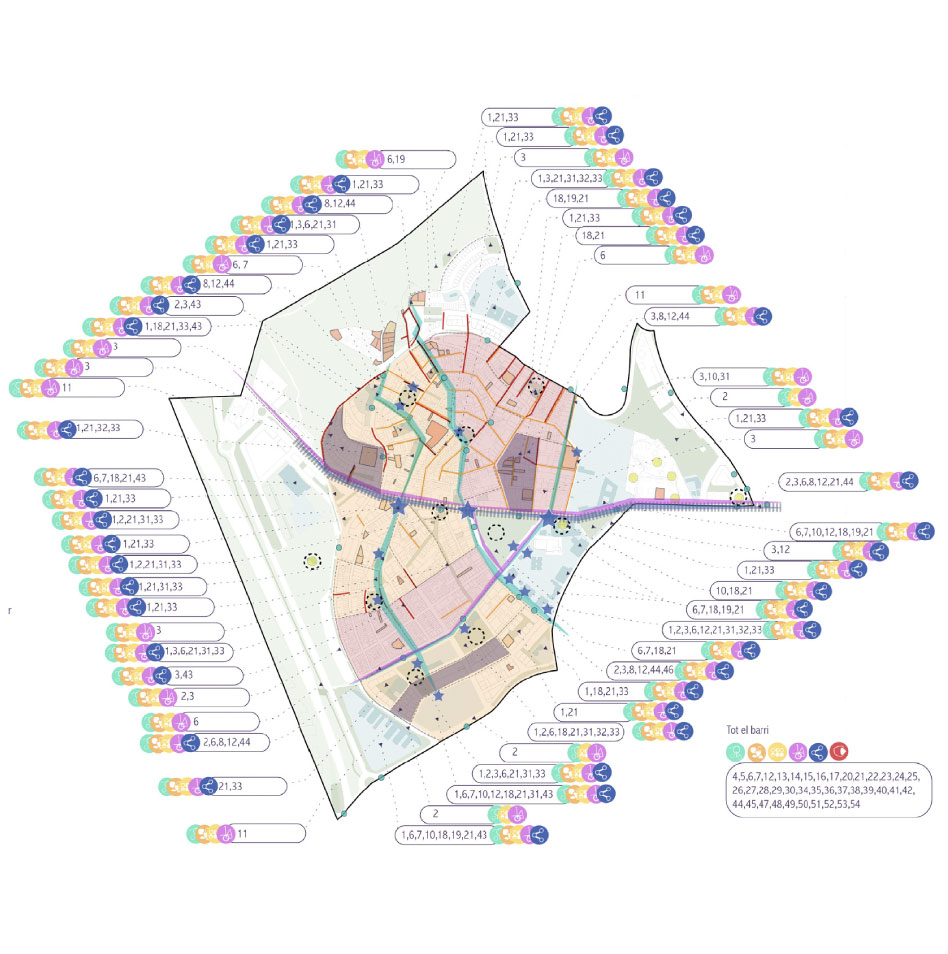

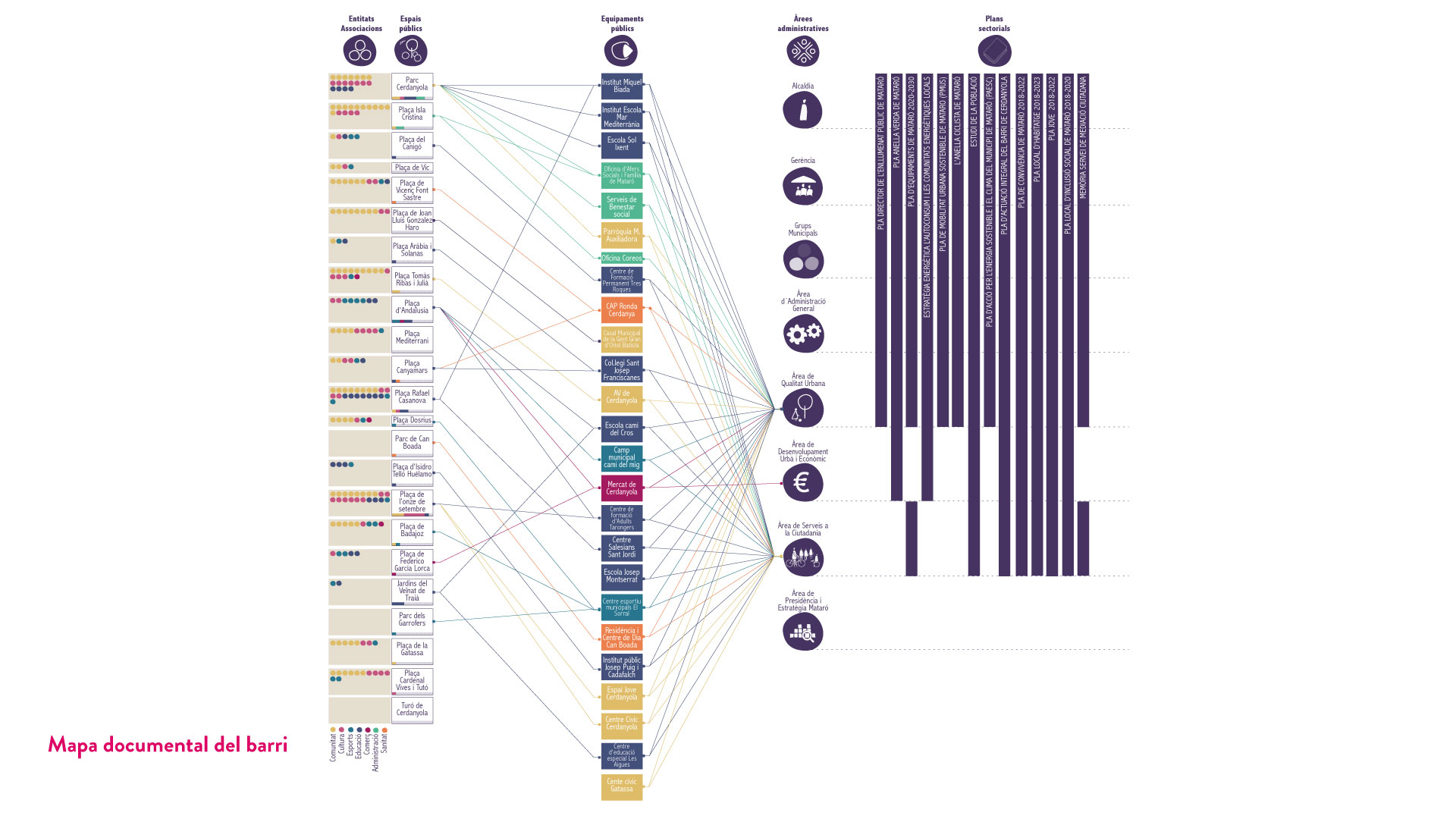

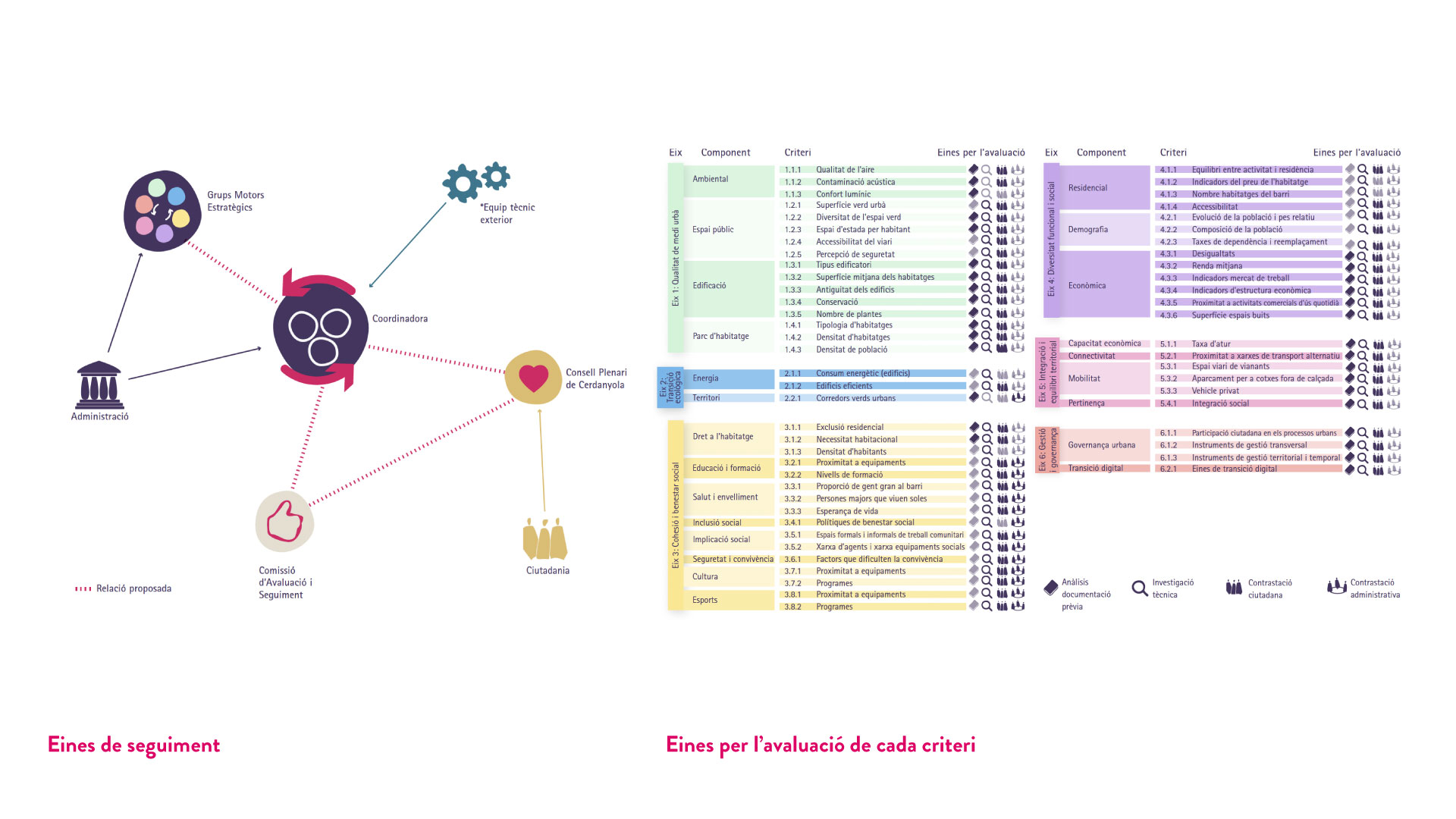

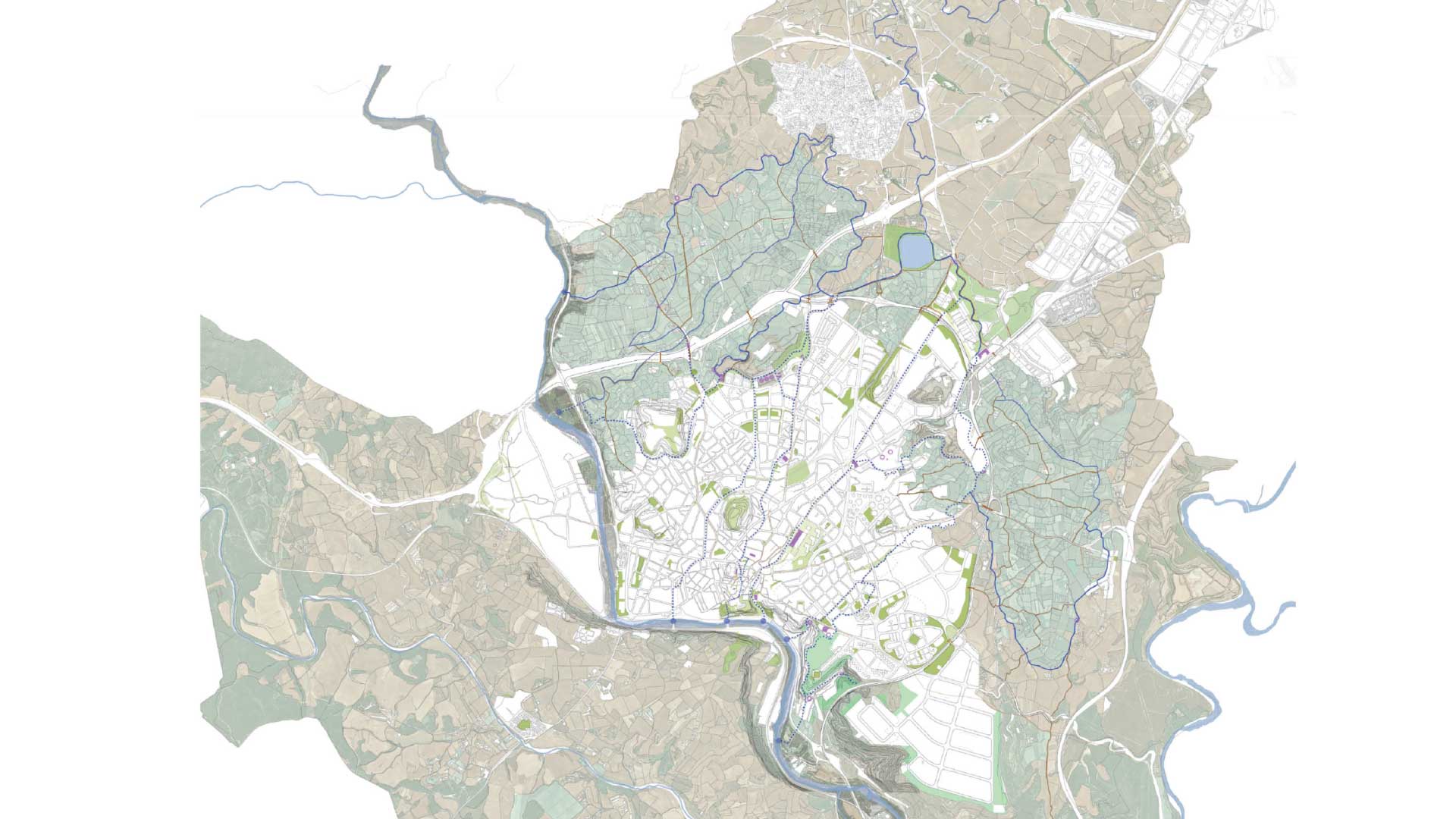

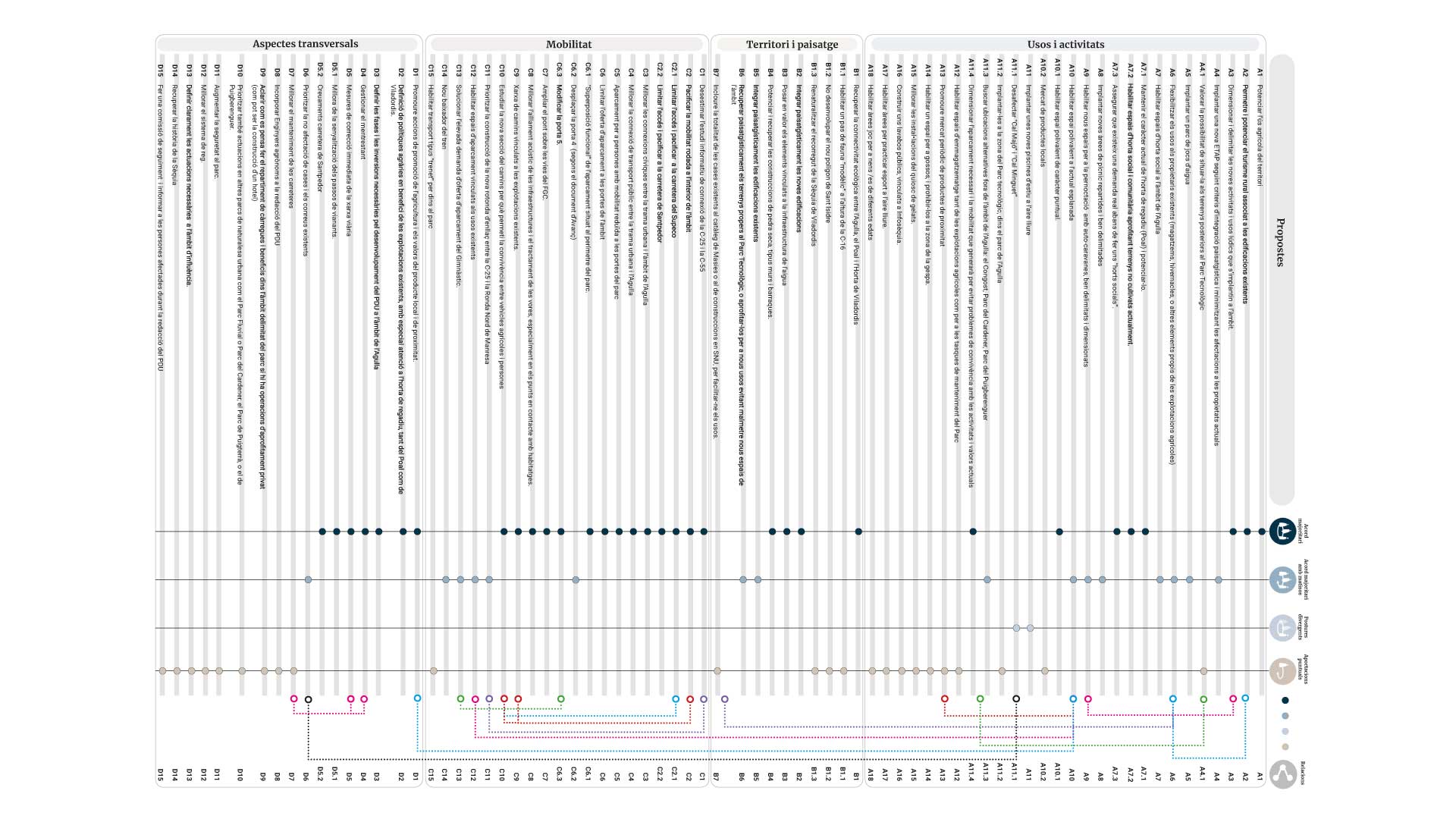

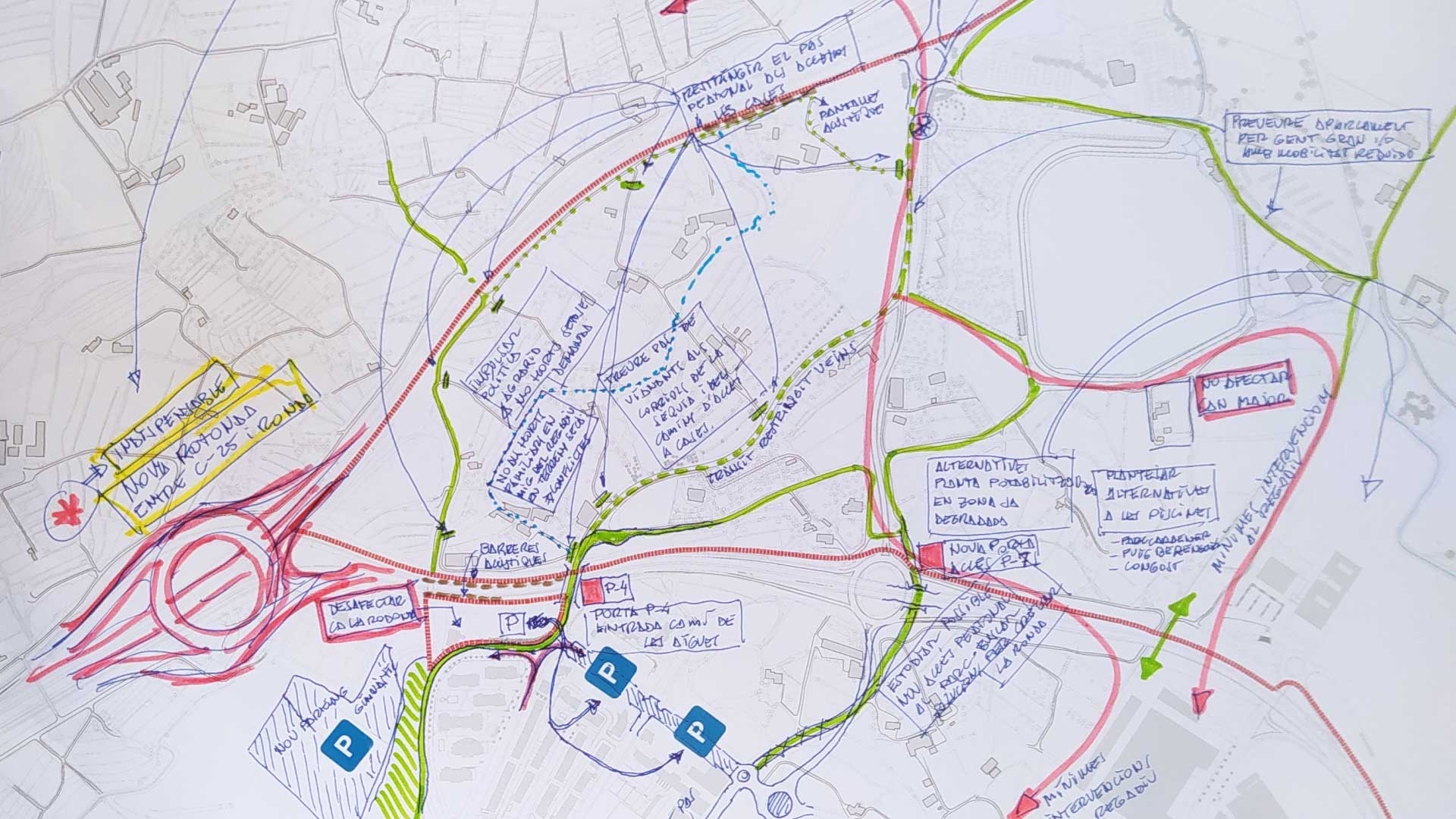

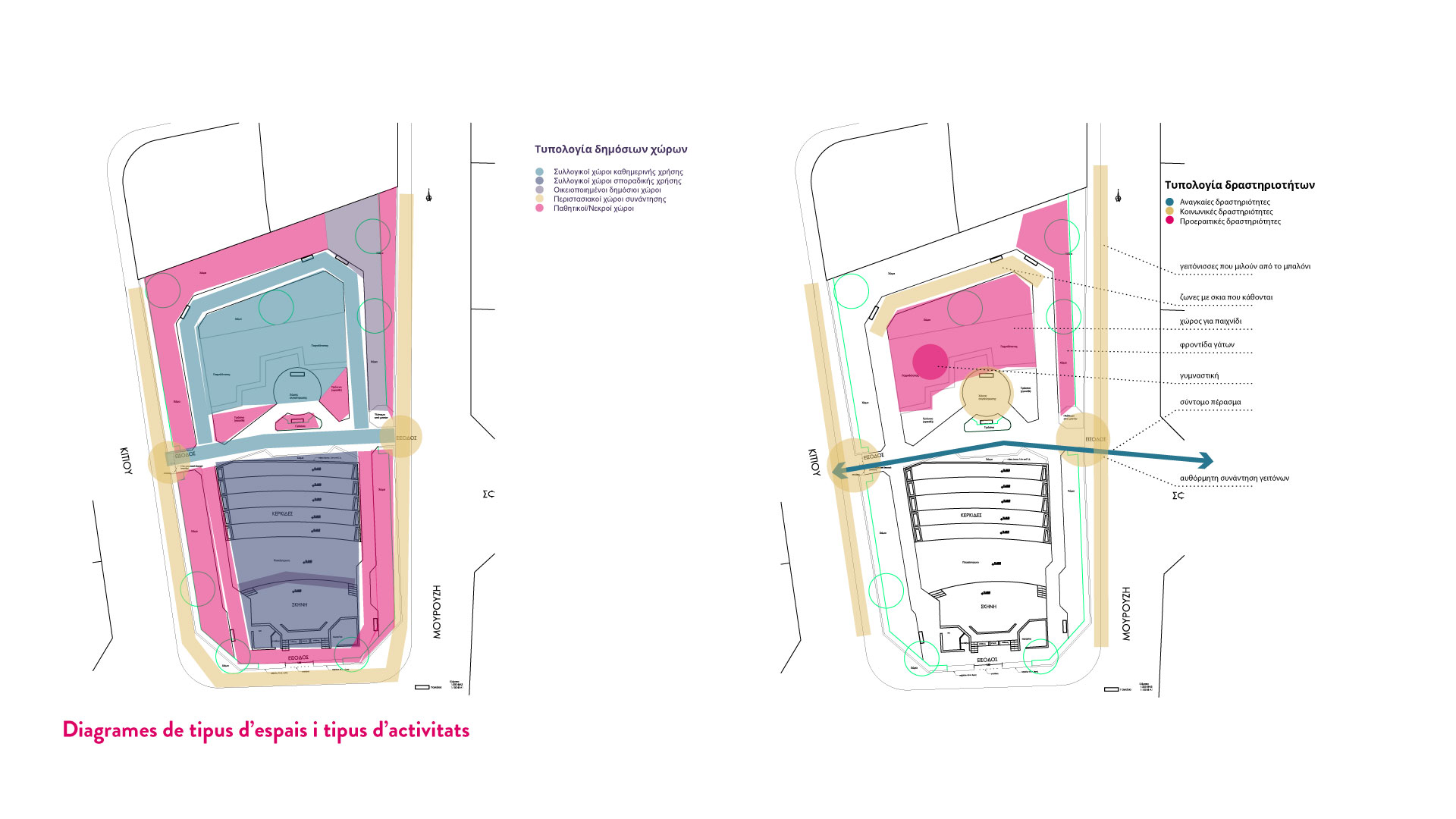

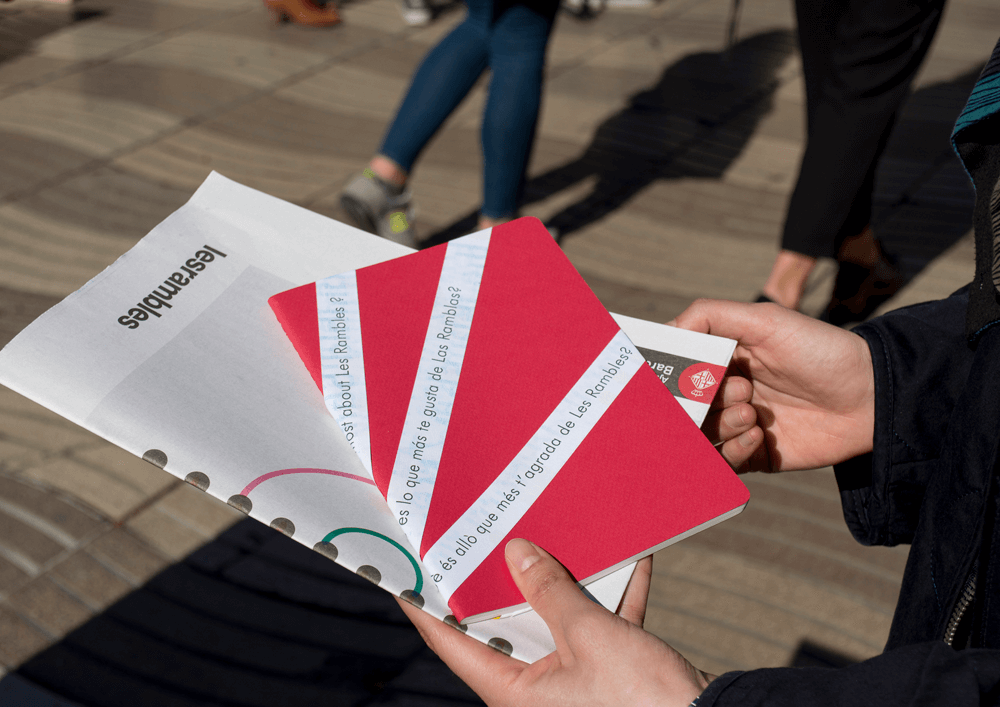

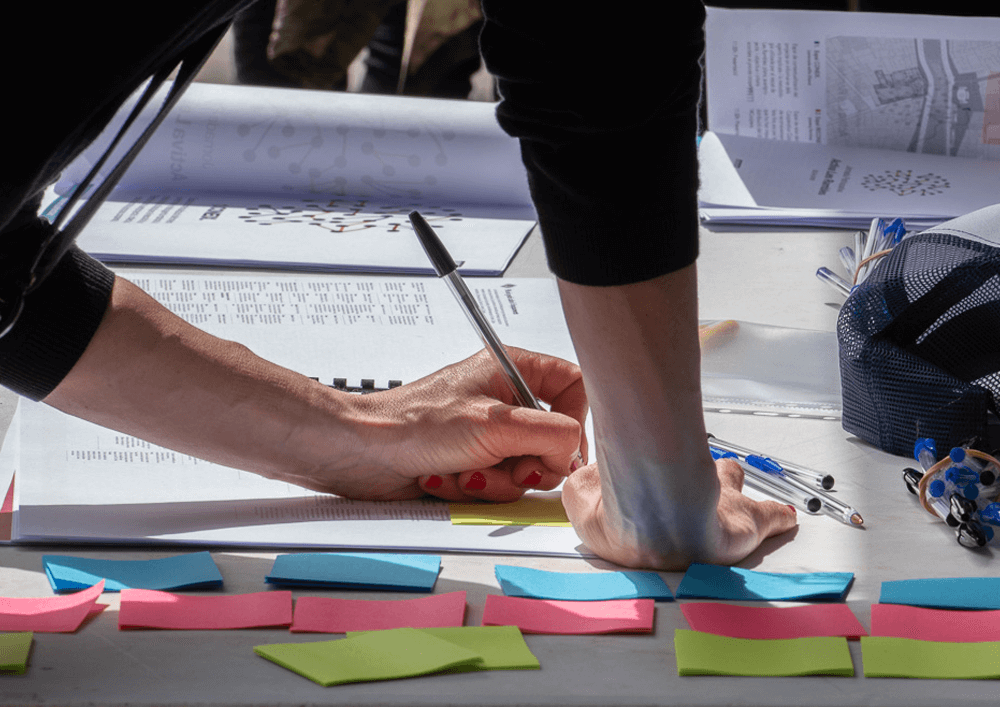

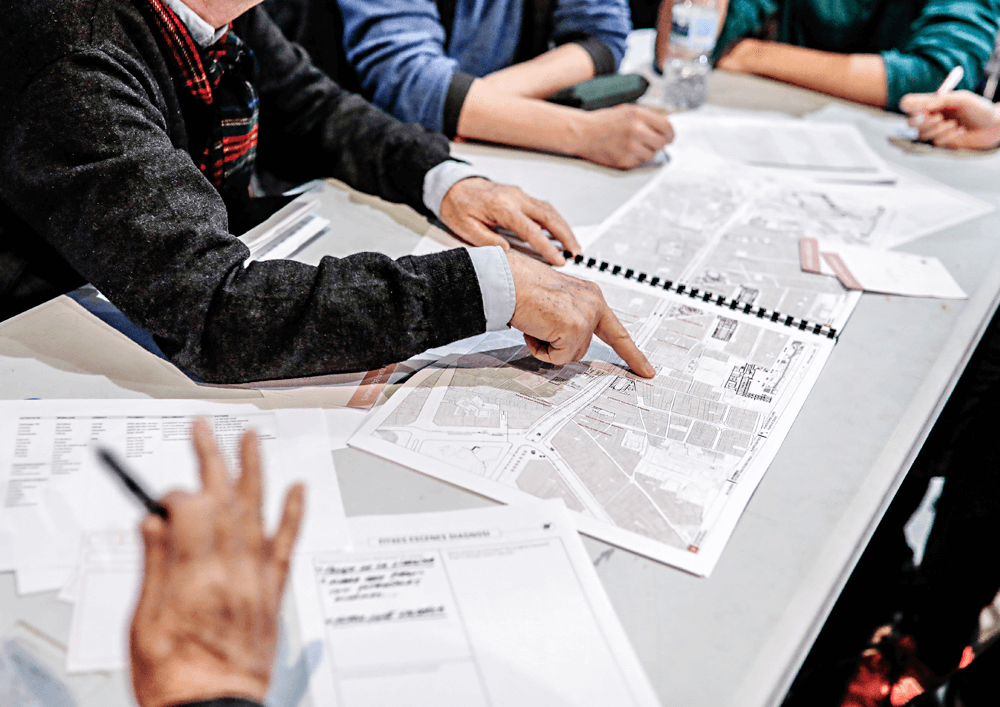

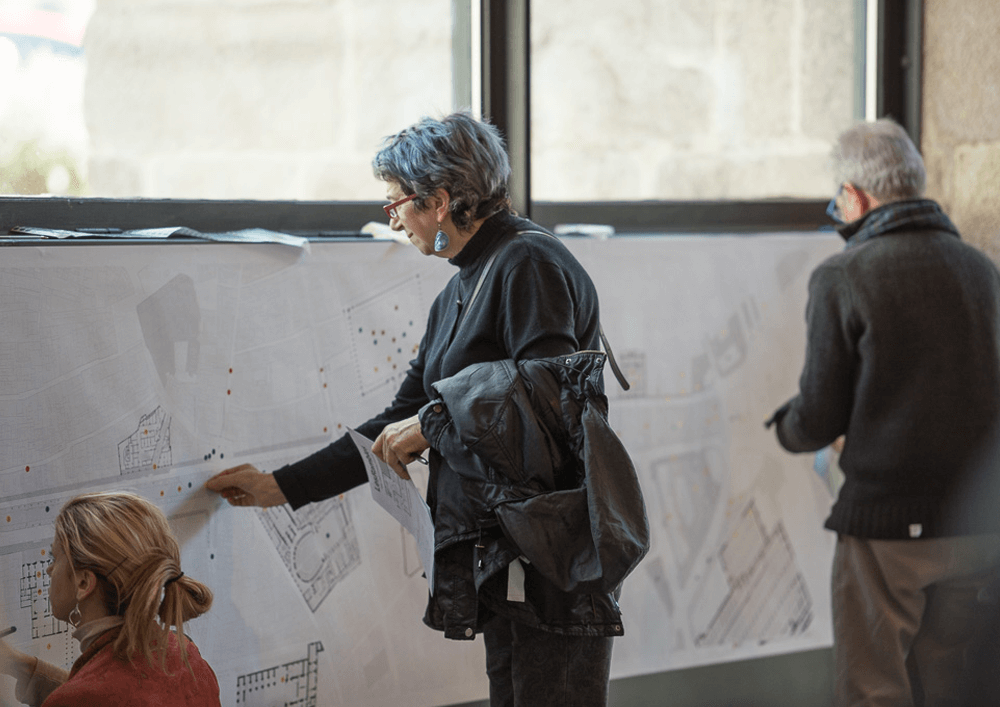

This process was developed as a cooperative work between technicians, citizens, and administration for the implementation of an urbanization and redesign proposal. With this innovative methodology as such, the aim was to make Rambla a diverse, flexible, sustainable, inclusive, accessible, consistent, secure, smart, contextualized, and comfortable place to be. The project is an inheritance and relief from the work done previously by entities, neighbors, and administration. With this process, the various agents worked jointly in order to rethink Rambles and extend this debate throughout the city.

The process for defining the improvement actions for “Les Rambles”, with its necessary physical and social interventions, proposed by the kmZERO team, is based on a diagnosis and agreed objectives between citizens, administration, and expert technicians.

The document resulting from the cooperative work is composed of strategies set that accompany the redevelopment of Rambles, which will be carried out between 2020 and 2026. Once again, the main challenge will be to do it as a joint task amongst the city’s agents.

Place

Barcelona

[1,620,343 habitants]

Scale of the project

Public space

Type of project

Urban Strategies

Citizen cooperation

Public space design

Duration

12 months [2017-2018]

Promoter

Muicipality of Barcelona,

Foment de Ciutat,

BIMSA

Team

UTE kmZERO: (AYESA –

Lola Domènech – Espinàs i

Tarrassó – Itziar González –

Arnau Boix)

Team kmZERO: Itziar Gonzàlez,

Arnau Boix, Lola Domènech,

Olga Tarrassó, Jordi Quiñonero,

Paul B. Preciado, Josep Selga,

Ole Thorson, Sergi Cutillas,

Ernest Cañada, Alberto Conesa,

Sebastià Ribot, Cristina Pedraza,

Julio Alcobendas, Esteve Boix,

Miquel Cañellas, Fernando Casal,

Konstantina Chrysostomou,

Pablo Cotarelo, Pablo Feu,

Iolanda Fresnillo, Nacho Guilera,

Gema Jover, Sira Llopart,

Eulàlia Miralles, Pere Mogas,

Jordi Parés, Daniel Pera,

Mireia Peris, Ignasi Querol,

Javier Rentero, David

Rodriguez, Francesc Sánchez,

Cristian Tapia, Anna Terricabras,

Carlos Utrillo, Javier Valencia,

Xavier Valls, Susanna Àlvarez,

Joan Escofet

Collaborators

Neighbors of Rambles de

Barcelona,

Agents and entities of

Barcelona