Territori Jujol in schools

The Territori Jujol in schools initiative aims to recognize and bring the figure and work of Jujol closer to the children from the territory itself, following the proposal of the Territori Jujol initial project, putting children at the centre of reflection, with the aim that they will be an active part of the project and help to broaden its impact on the educational community and on the public.

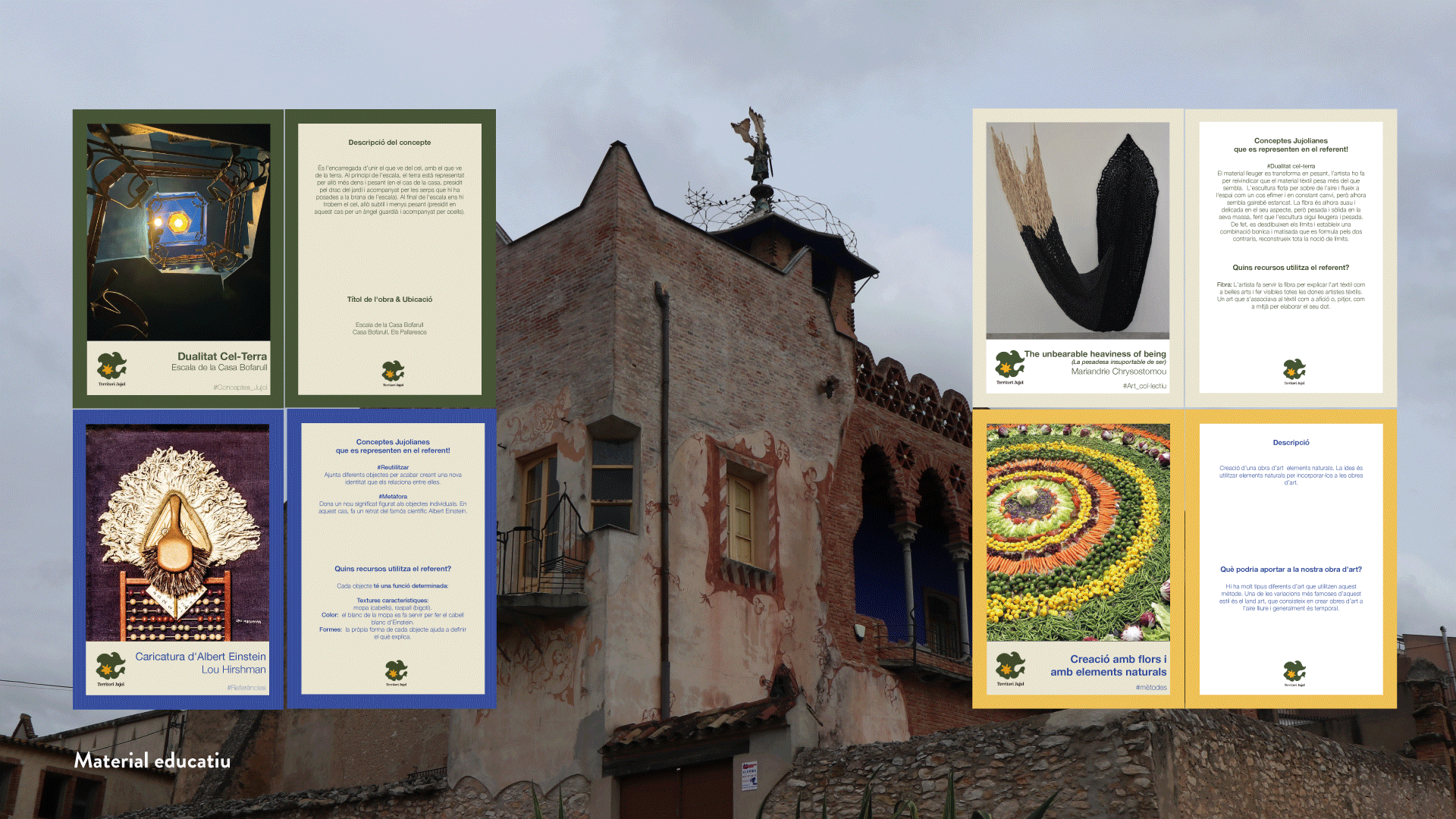

The proposal is based on the work carried out, and the documentation collected within the framework of the Territori Jujol project, an initiative developed by the Reus Higher Technical School of Architecture and COFO architects.

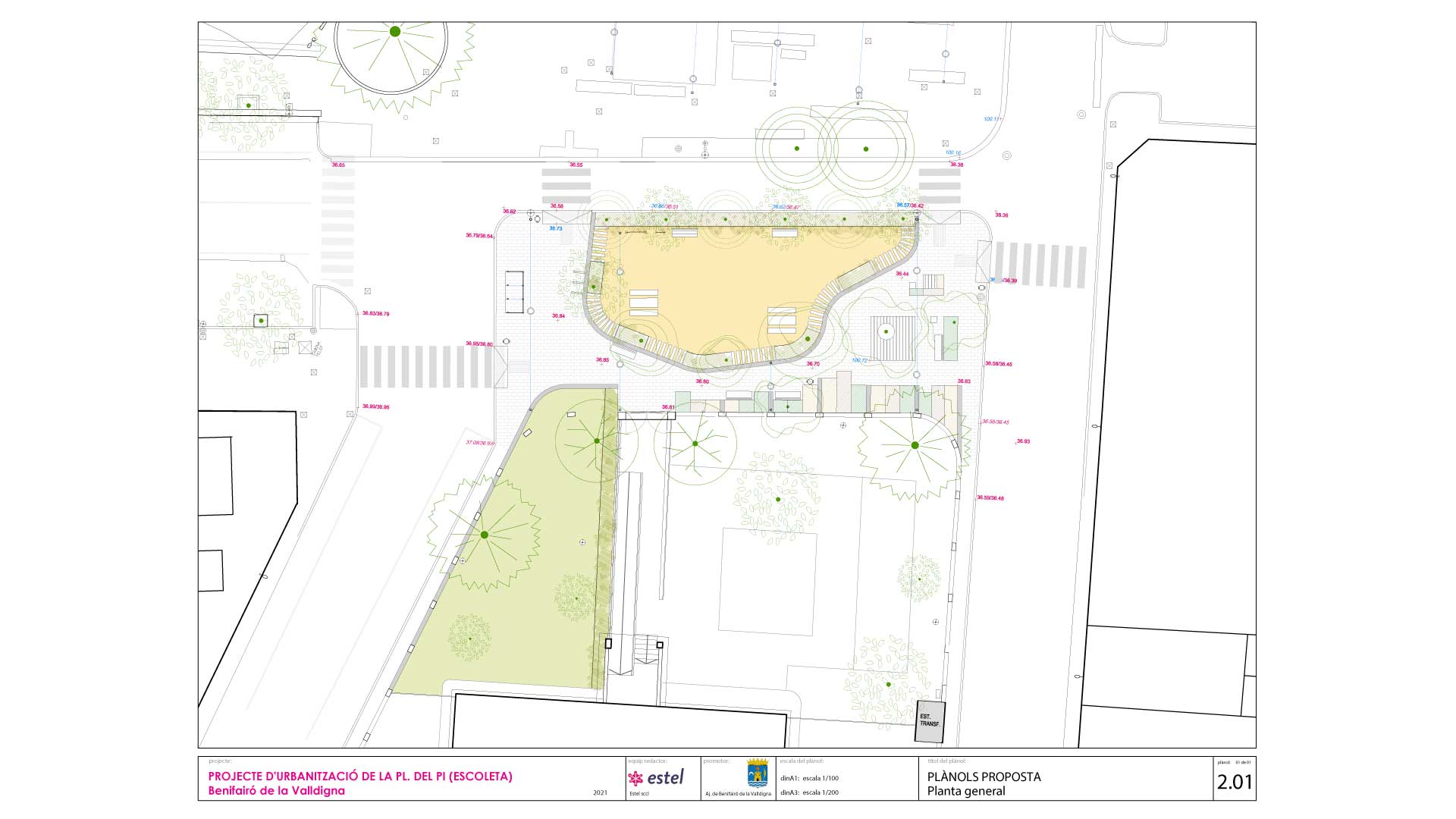

The activities, carried out inside and outside the classroom, have as a goal to explore the children’s ideas, to extend it using the didactic material to other educational centres and the citizens. One of the objectives, is to generate, through work in schools, a network of complicity between the municipalities that form the Jujol Territory.

The general objectives of the project are:

- Learn the work and biography of Jujol.

- Include children in the process of learning and reading the work and the character of Jujol from the projects located in the municipality.

- Dealing with topics such as design, materiality, landscape, Jujol’s biography through a creative process.

- Disseminate the works of Territori Jujol in the school, beyond the students who directly participate in the activity.

- Promote the networking of the schools of the different municipalities that work on the projects of the Jujol Territory.

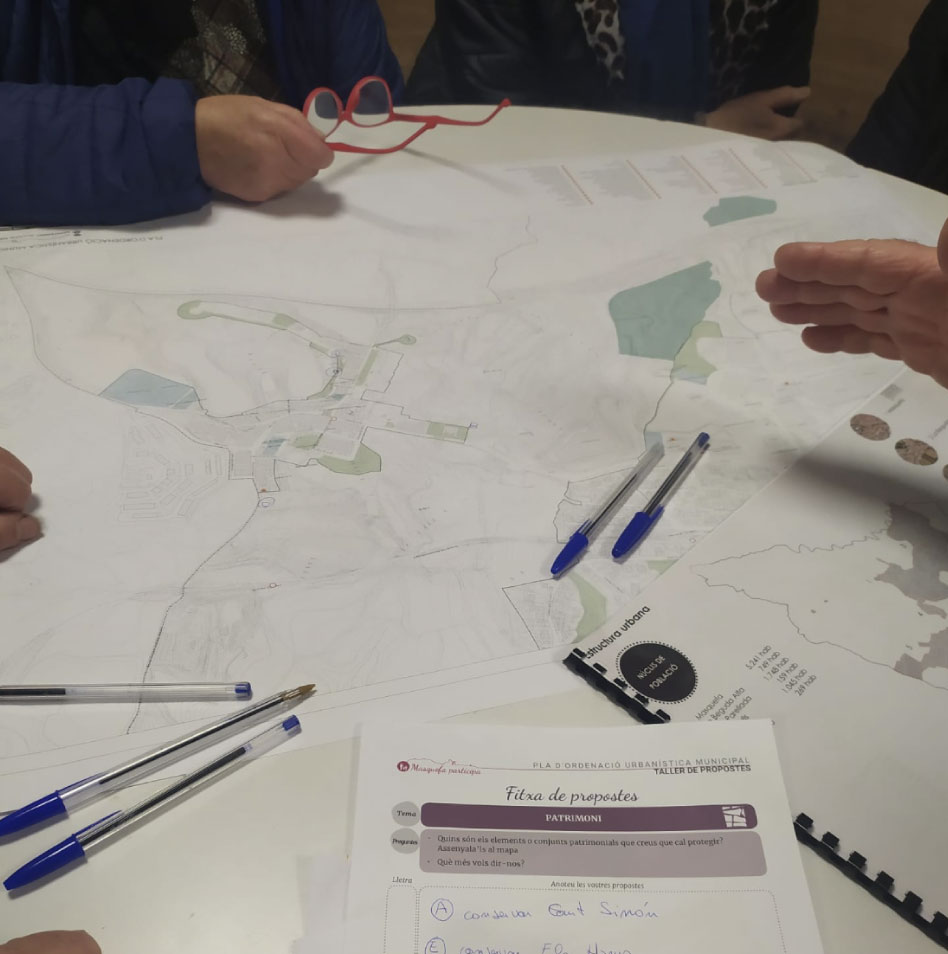

In order to achieve the objectives of the series of workshops, it is proposed to work both experientially and conceptually, and thus understand the complexity of the figure of Jujol from the point of view of his creative thinking and his ability to transform reality.

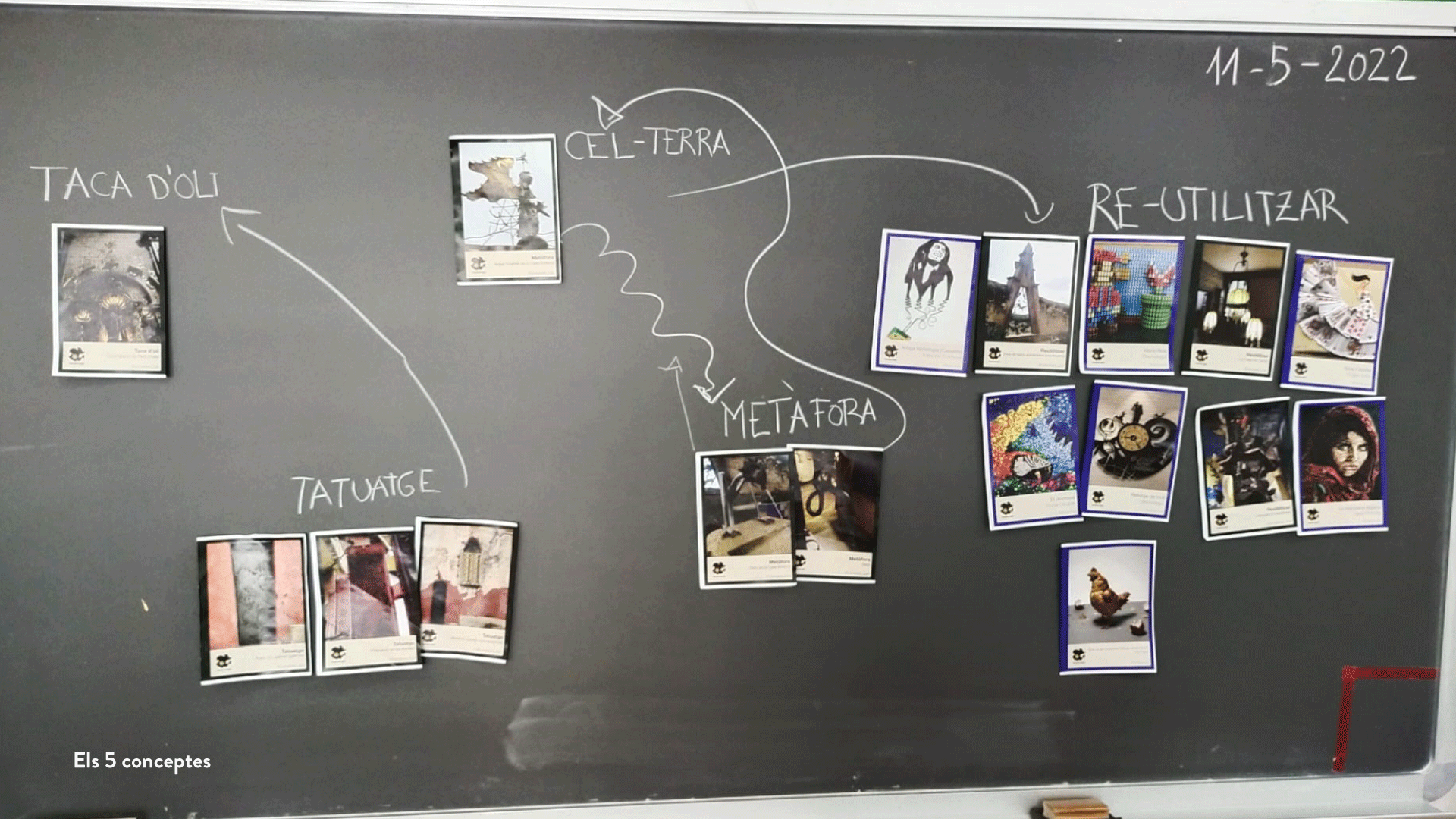

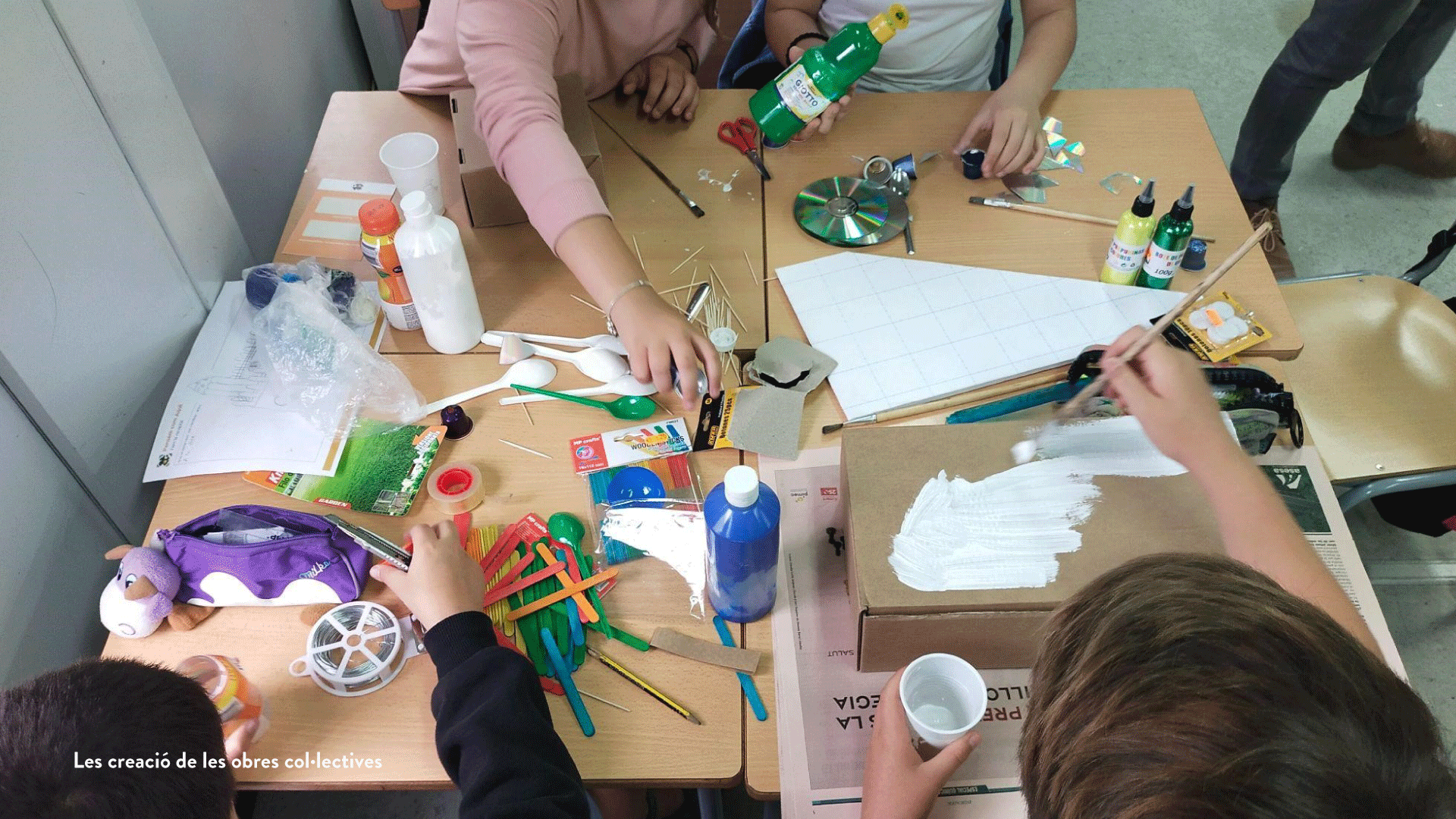

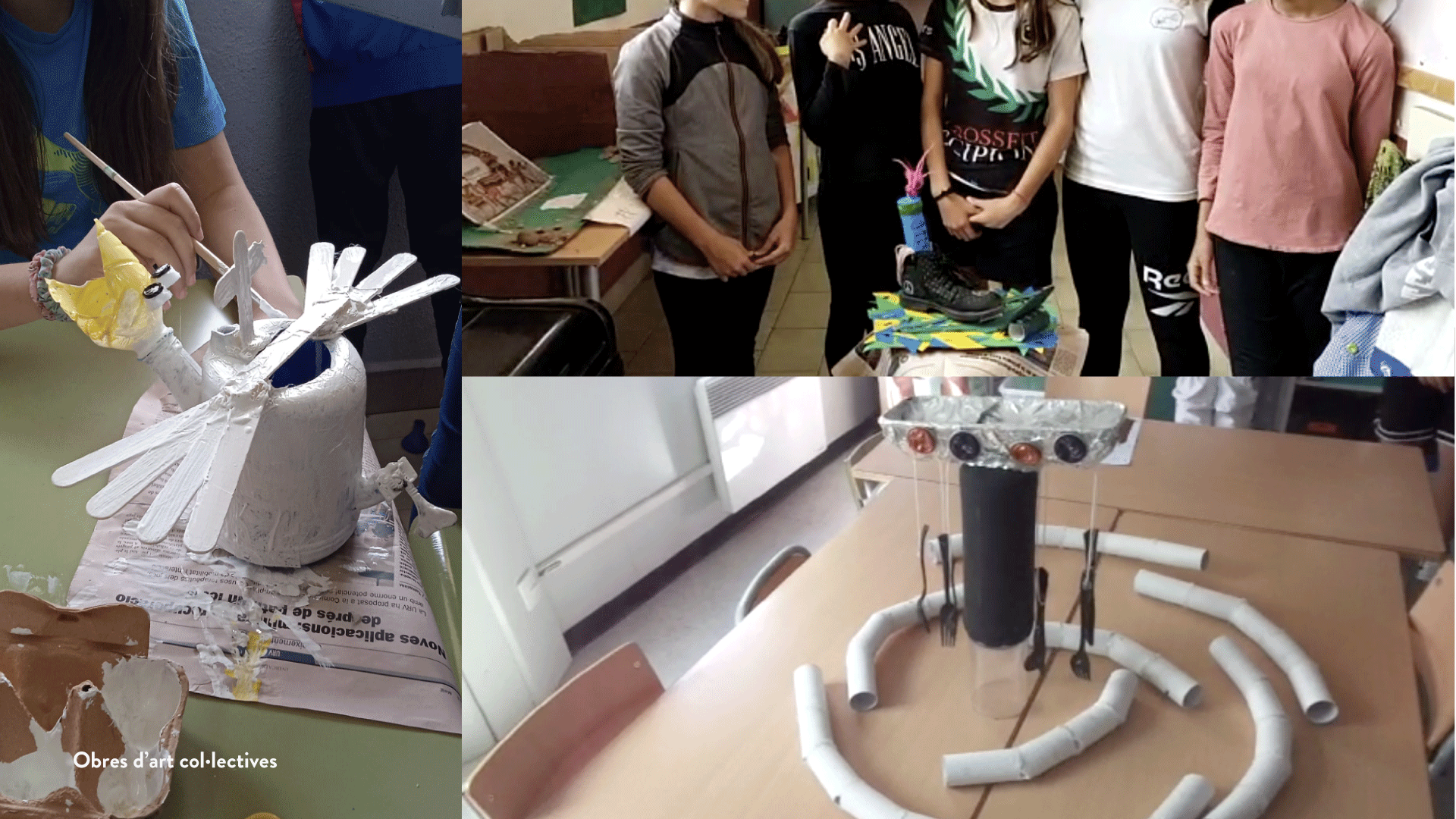

This cycle of workshops addresses a process of joint creation that begins with a visit to a Jujol work adopted by the school, and which then and during the following work sessions will give shape to the ideas of the students . This work is conveyed around 5 key concepts, which will allow us to link Jujol’s work with the children’s work, applying them in the transformation of an everyday object into something different.

The 5 workshops are:

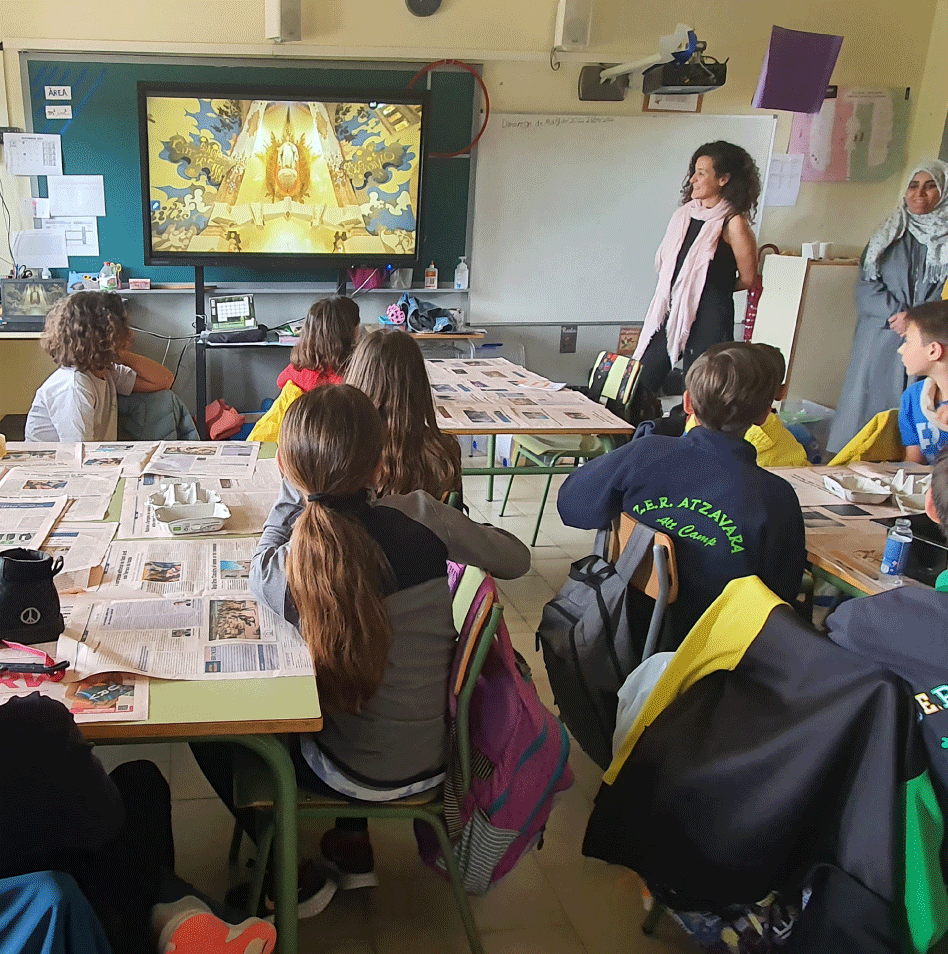

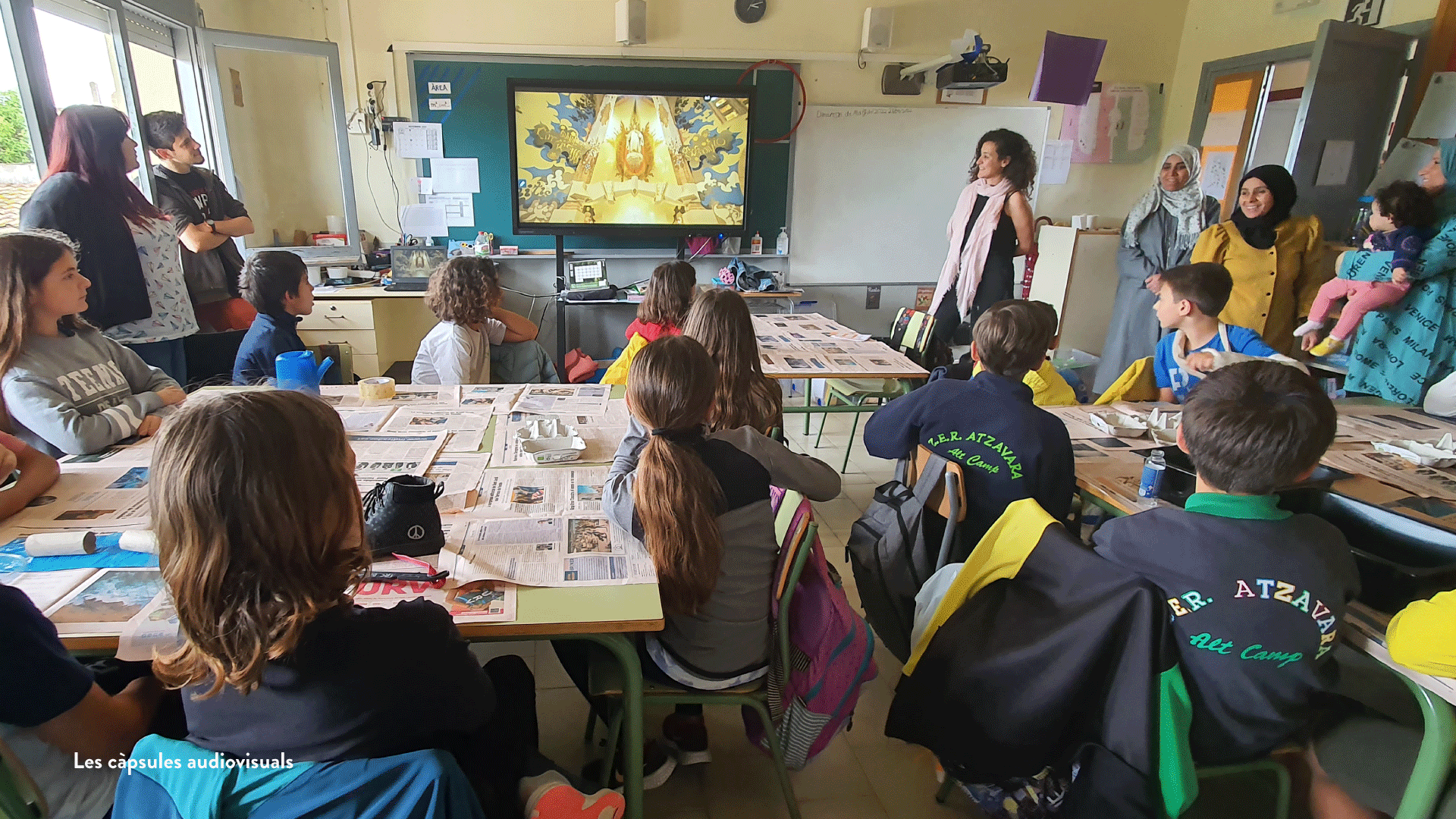

- Workshop 1 – We discover Jujol [raise awareness, motivate, experiment]: activity carried out in the adopted work, which consists of a guided tour and which aims to bring the creation of Jujol closer to the students in a direct and experiential way.

- Workshop 2 – We rediscover Jujol [experience, analyze]: activity carried out in the classroom, with the aim of deciphering the concepts to Jujol’s methodology for his works, and experiencing it individually.

- Workshop 3 – We think how to Jujol [imagine, collaborate]: activity carried out in the classroom, with the aim of defining the main lines of a collective creation of a larger format.

- Workshop 4 – We create like Jujol [transform, collaborate]: activity carried out in the classroom, with the aim of working together to develop the ideas defined in the third workshop.

- Workshop 5a – We explain Jujol [explain] : autonomous activity in the classroom led by the teachers. It consists of making a recording where each group explains their work.

- Workshop 5b – We celebrate Jujol [do, share]: closing activity, to share the results and disseminate the work done. This part takes place outside the school and is open to all citizens.

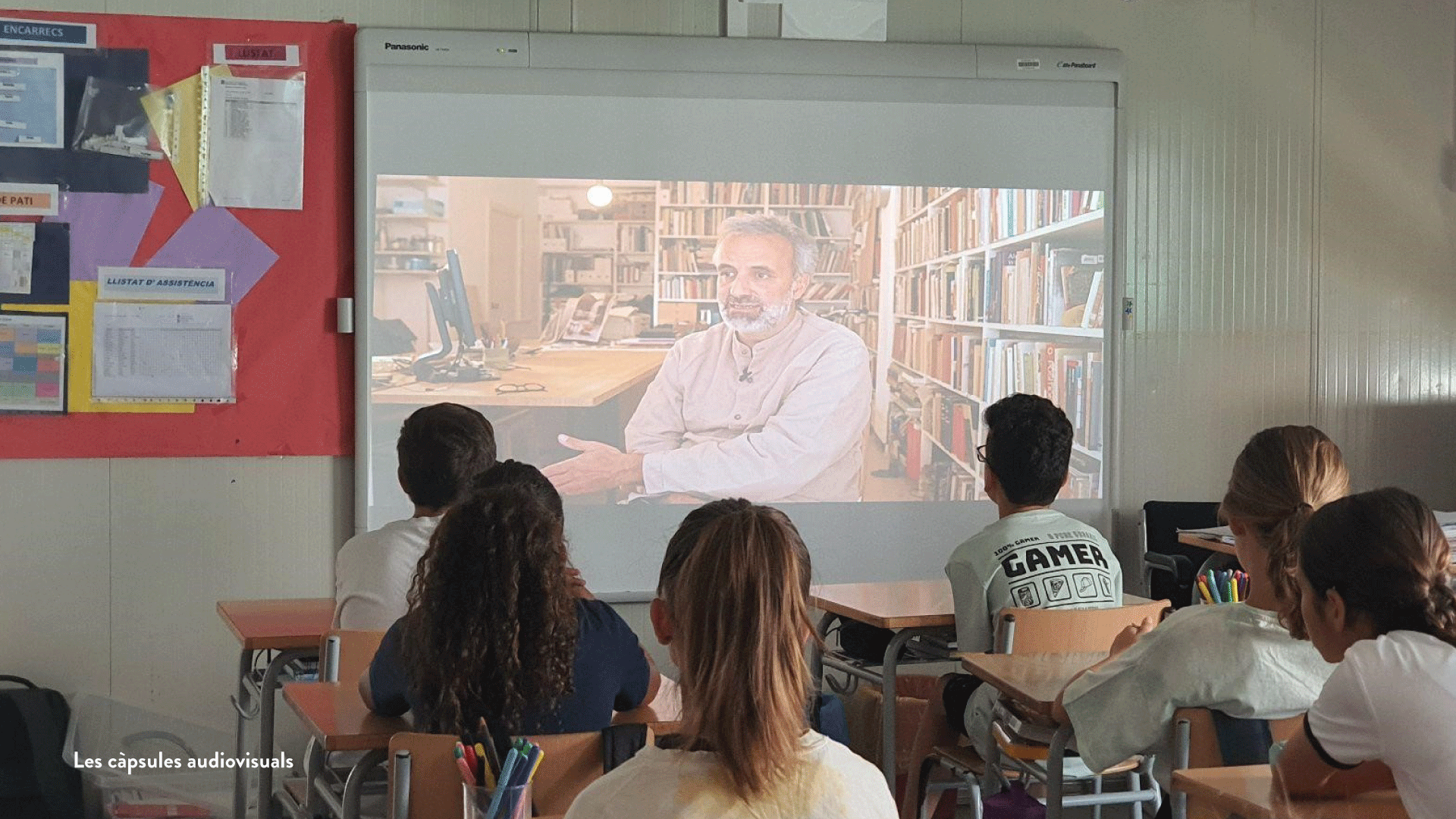

Each one of the workshops is accompanied by an audiovisual capsule where the facilitators of Territori Jujol begin to introduce some of the topics that will be worked on in the face-to-face workshop. They aim to motivate and present key concepts.

In this pilot test there are two schools participating in the project, with a total of 3 class groups:

- The Bràfim School: in this case, the activity is carried out with the upper primary cycle (class group made up of boys and girls from 5th and 6th grade).

- The School Arquitecte Jujol dels Pallaresos: In this case, the activity will be carried out with the 5th year of primary school, made up of two class groups.

The idea is that once the process is finished, this process can be extended to other schools.

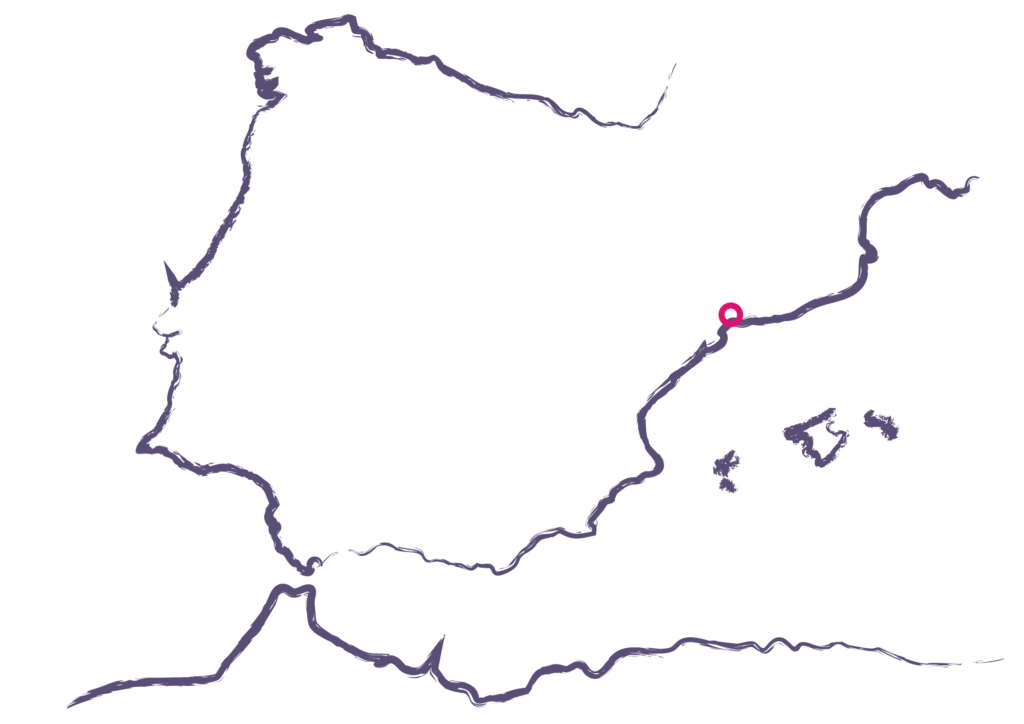

Place

Tarragona

[135,966 inhabitants]

Scale

Supra-municipal

Type of project

Citizen cooperation

Duration

5 months [2022]

Promoter

Territori Jujol

Universitat Rovira i Virgili

Fundació “la Caixa”

Team

*estel (Uri Serra, Konstantina

Chrysostomou, Marc Deu

Ferrer, Arnau Boix i Pla, Alba

Domínguez Ferrer)

Roger Miralles Jori

Collaborators

María González Cañadell

Guillem Fonts Ferrando

Bràfim School educational

team

Pallaresos School

educational team

Presentation

Watch the videos on YouTube