Currently, in the city of Barcelona, there are a total of 180,000 dogs registered with microchips, which is more than the population of children under 12 years old. This means that 25% of the city’s population lives with a dog. Incredible, isn’t it?

Studies show that young adults under 40 years old, the Millennials, have recently surpassed Boomers in dog adoption. In the United States, it is estimated that more than half of Millennials live with a dog. The rate of cohabitation with companion animals is even higher among people with university education and stable incomes, the same people who are more likely to delay marriage, having children, and homeownership beyond the established timelines of previous generations. But it’s not just that. Dogs can be much more: a way to root oneself in a new place, a roommate for people living alone, and they can play an important role in helping people’s mental health.

Taking care of a dog is one of those life-changing experiences. Or at least, it makes you see and live situations that you would have never experienced otherwise. Personally, it has increased my awareness of the micro-landscape of my neighborhood and how dogs interact with public spaces, and how I – as a dog companion – interact with public spaces.

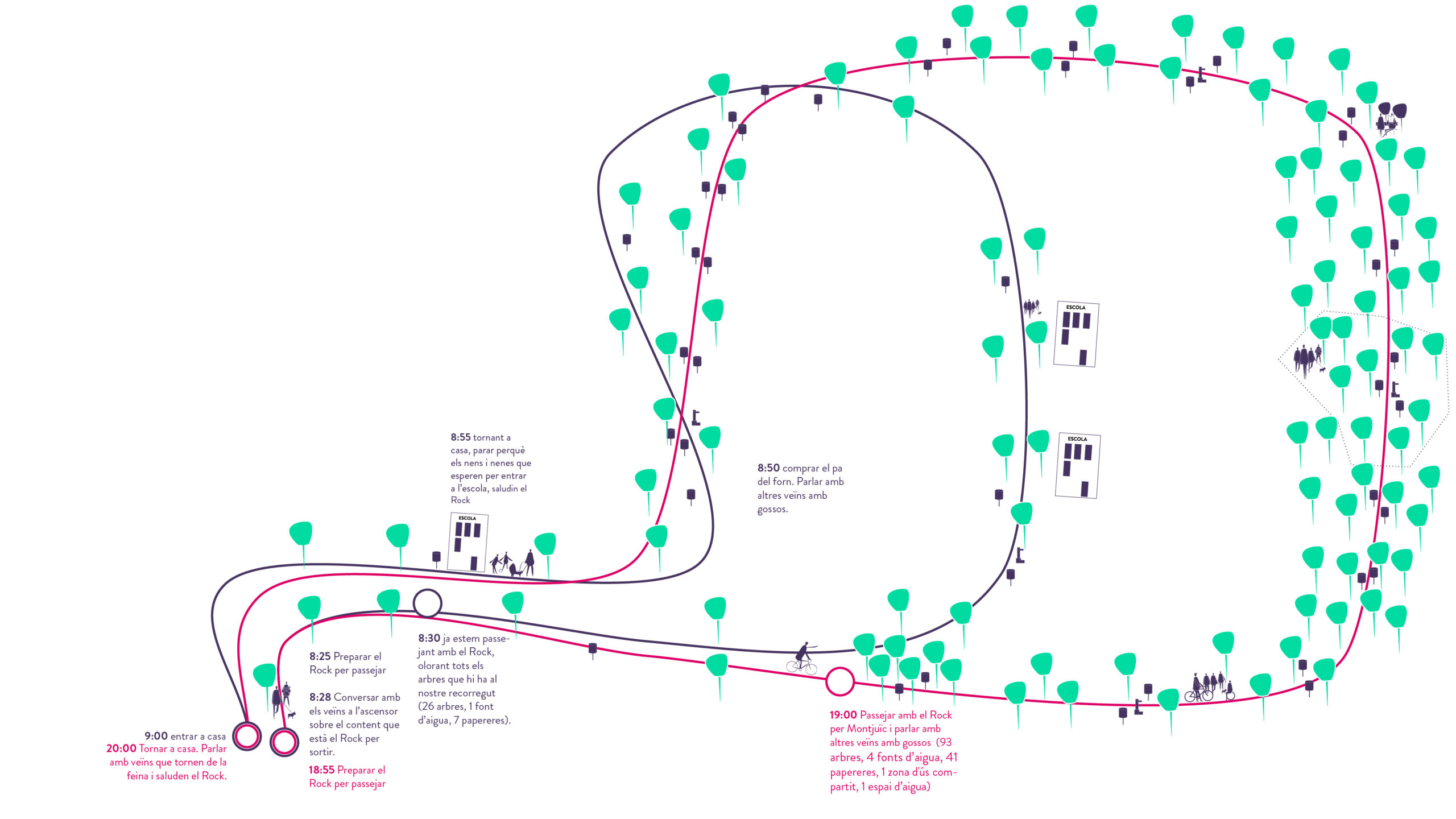

A typical day with my dog would be:

- 8:25 Getting Rock ready for a walk.

- 8:28 Having a conversation with neighbors in the elevator about how excited Rock is to go out.

- 8:30 We’re already out walking with Rock, sniffing all the trees along our route (26 trees, 1 water fountain, 7 trash cans).

- 8:50 Buying bread from the bakery. Chatting with other dog owners in the neighborhood.

- 8:55 On our way back home, stopping so that the kids waiting to enter school can greet Rock.

- 9:00 Entering the house.

- 18:55 Getting Rock ready for another walk.

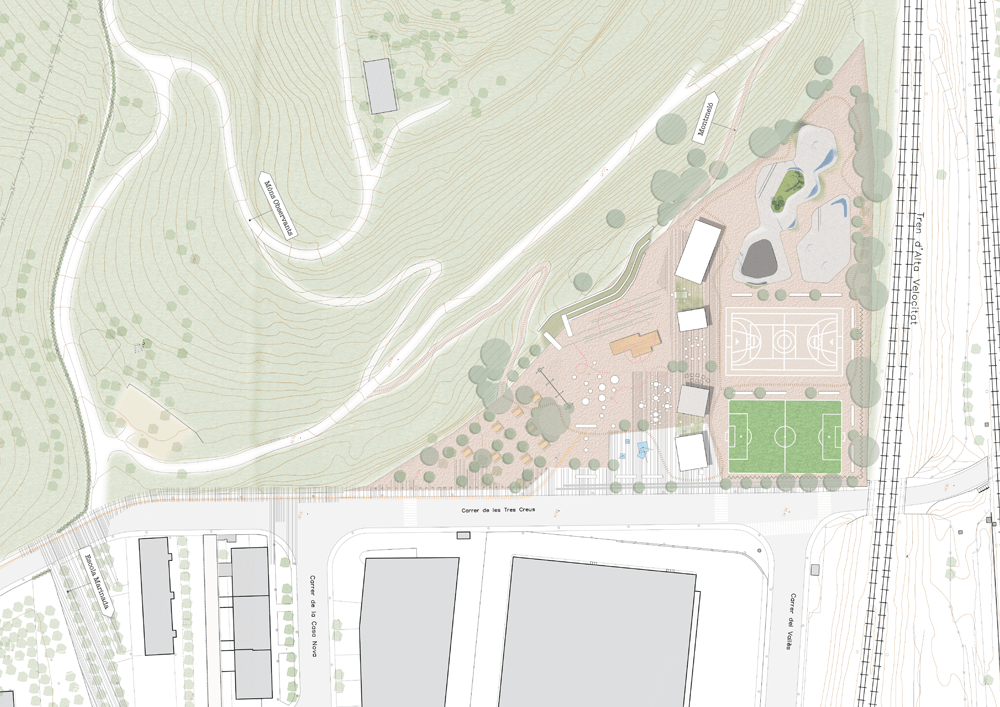

- 19:00 Walking with Rock in Montjuïc and chatting with other dog owners (93 trees, 4 water fountains, 41 trash cans, 1 shared-use area, 1 water space).

- 20:00 Returning home. Talking to neighbors returning from work who greet Rock.

The interaction and connection with my neighbors and the environment where I live are understood differently. It’s no longer just about having a beautiful and pleasant landscape with seating areas, but also about having waste bins, rubbish cans, and water fountains. And since I walk in the evening, it’s important for the space to be well-lit and for me to feel safe. It’s another way of perceiving the urban space and the role of a dog in this ecosystem.

Let me quickly explain the four significant things my dog has taught me about my neighborhood and its people:

The dog as a triangulator

Although the topic of dogs can be quite contentious among people who feel comfortable with them and those who don’t, I increasingly see dogs as great triangulators in public spaces.

But first, what does triangulation mean?

Triangulation can be defined as “the characteristic of a public space that can bring together strangers. Usually, it is an external stimulus of some kind.”

A bus stop can be an element of triangulation. A person playing music on the street can be, too. It could be any element that makes two unknown people pause for a second and talk. That being said, a dog is a great triangulator.

While walking my dog, I have met and interacted with more neighbors in my neighborhood than in the past five years I have lived there. The dog makes people lower their guard, slows down their pace, and encourages greetings, conversations, and smiles. The last time I experienced this kind of “unforced” interaction, naturally, was when I bought a bouquet of flowers. Just as the bouquet of flowers made my neighbors talk to me about the flowers, smile, or greet me, the same thing is happening now with my dog.

Dog recreation areas as spaces for socialization

When you walk a dog, you automatically become part of an informal club of “people who care for a dog.” If you don’t have a dog, it’s not as easy to enter this group since the conversation typically revolves around your dog, other dogs, and the weather.

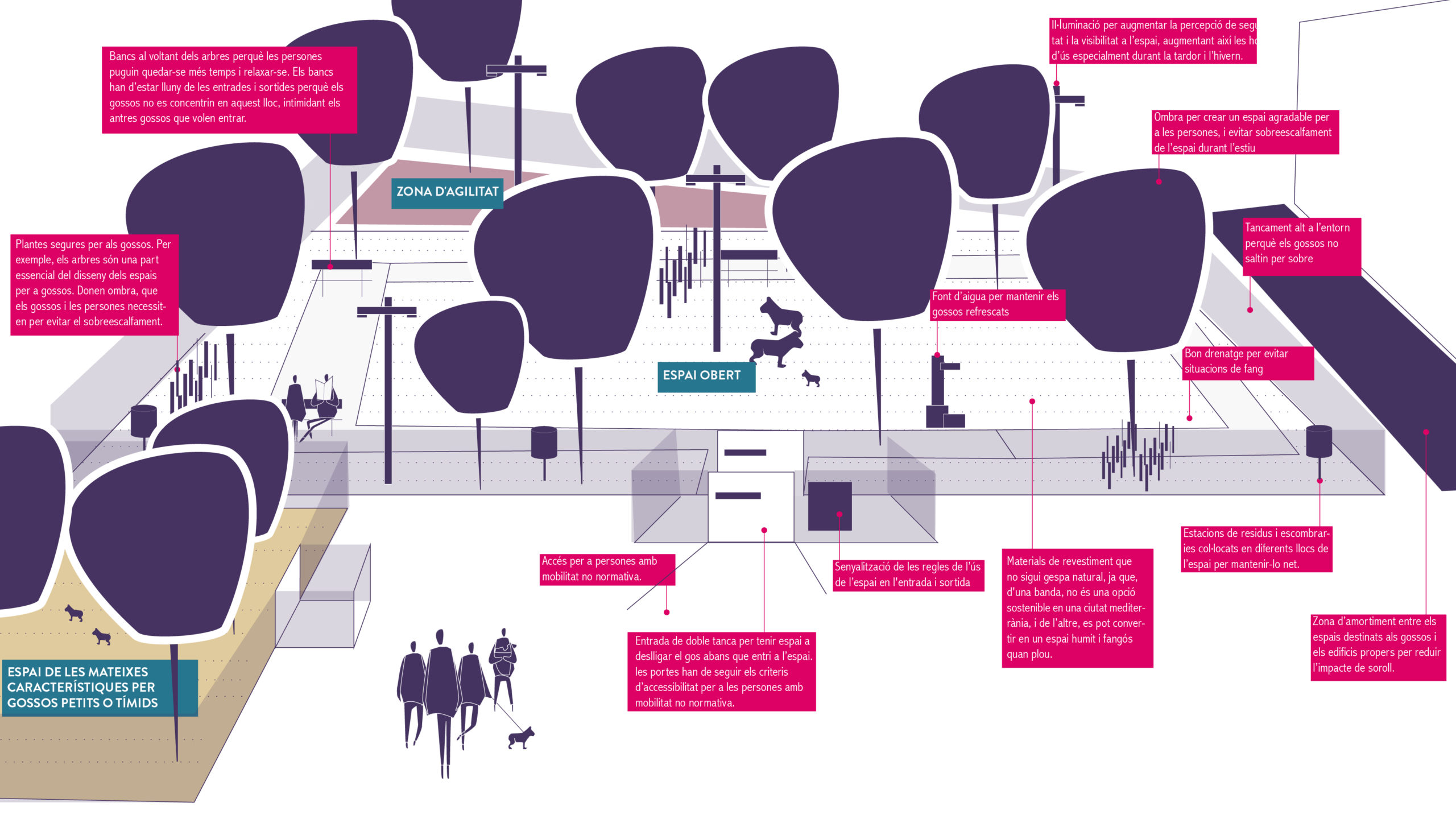

Dog recreation areas, then, are the spaces where these strangers meet and talk. Dog caregivers need these spaces—a safe environment where their dogs can exercise regularly and safely because dogs enjoy walking, running, and socializing with other dogs. It is a vital part of a dog’s life when living in an apartment in Barcelona.

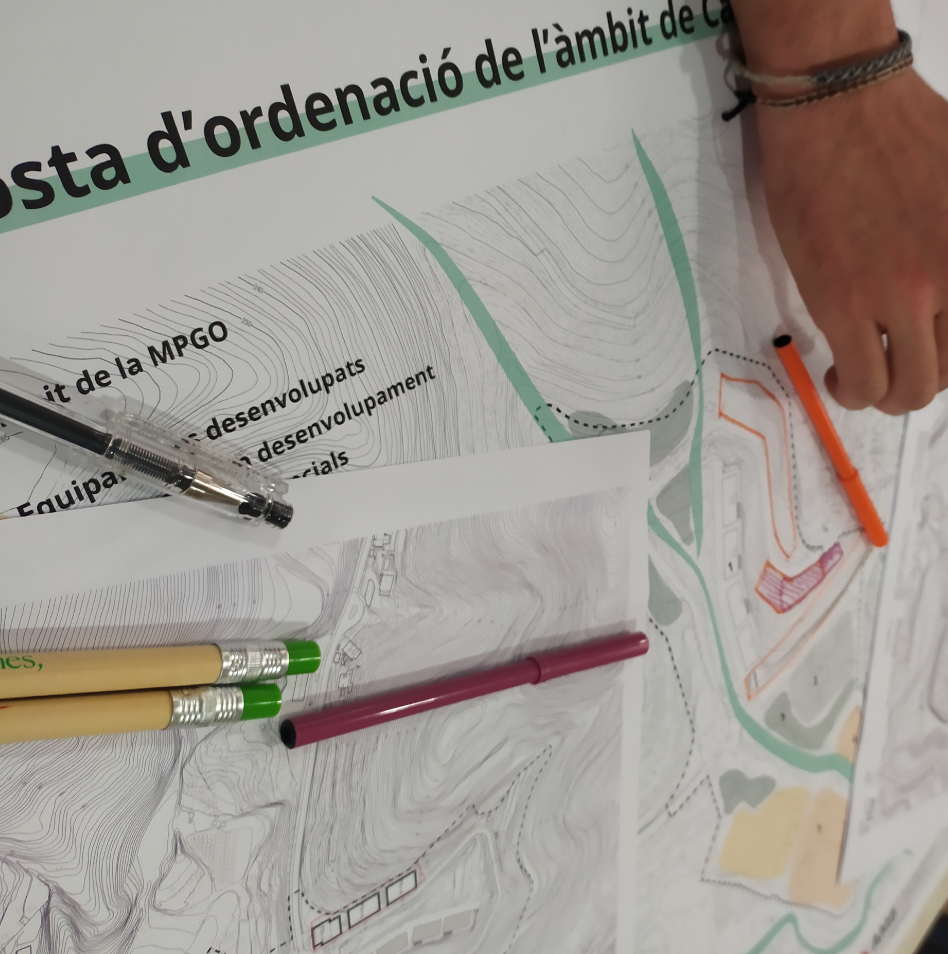

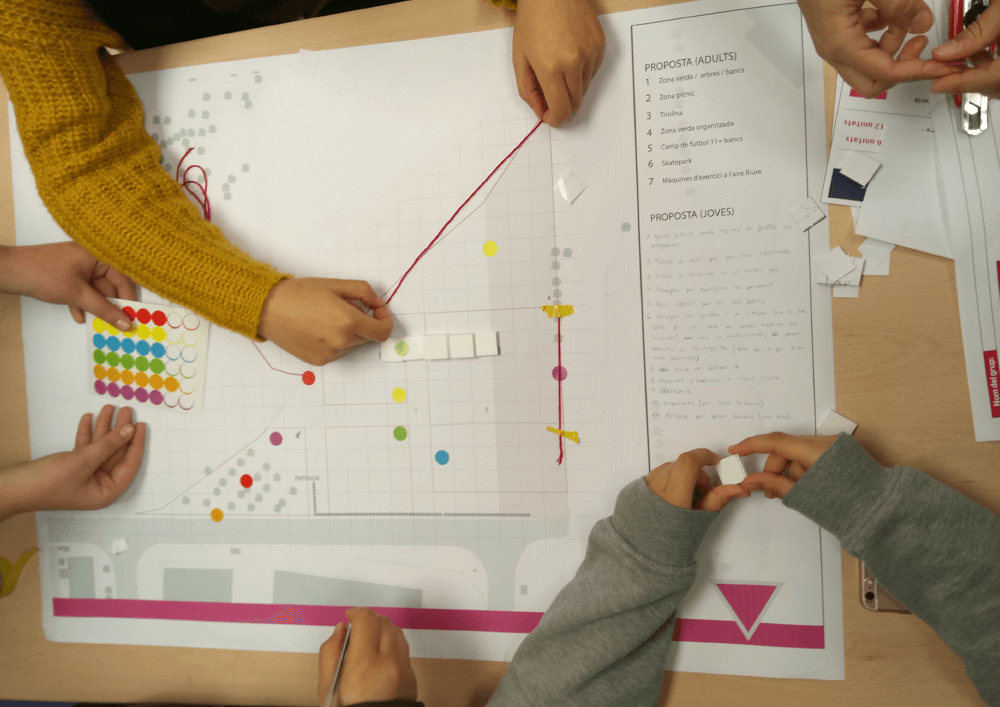

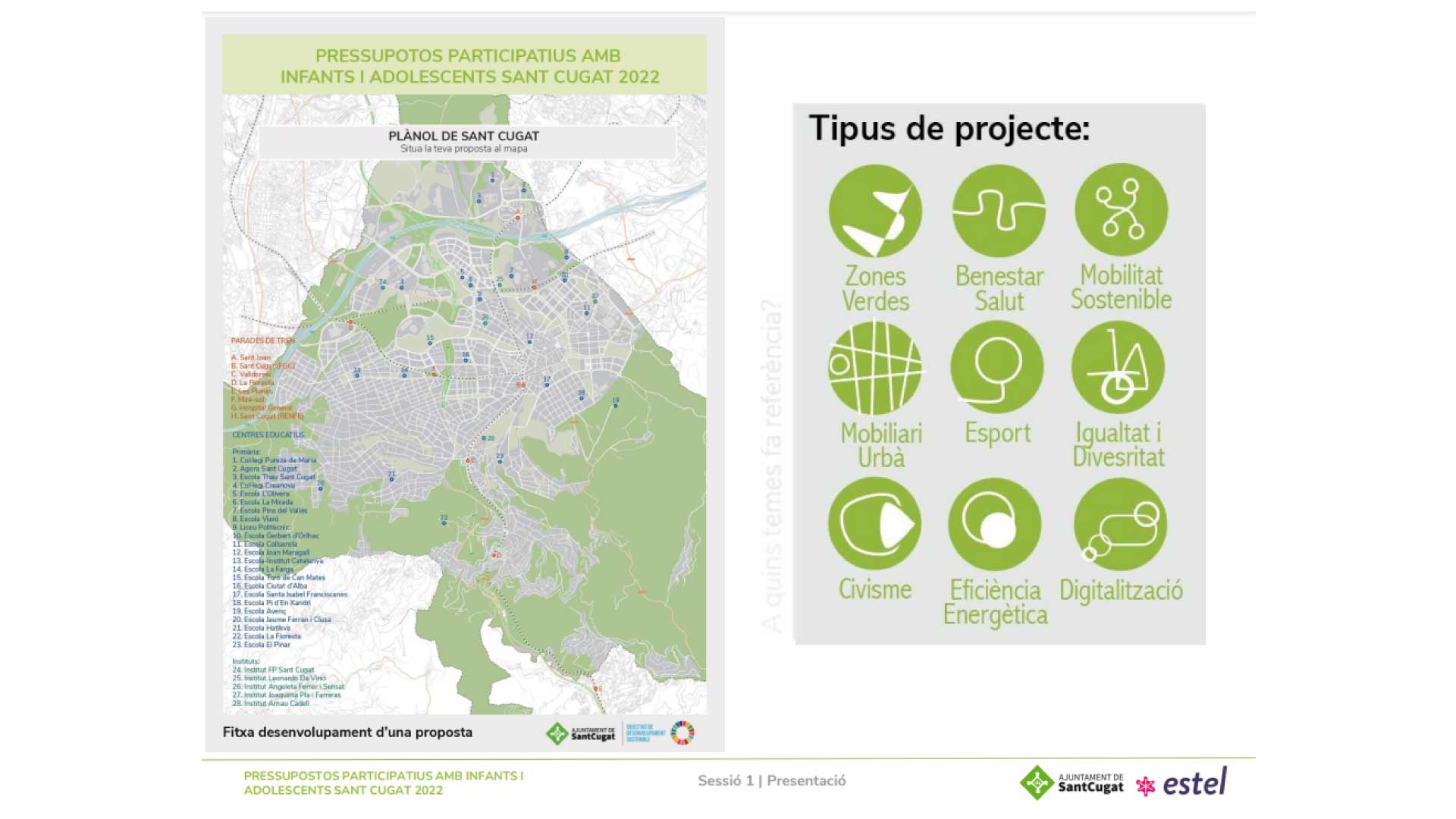

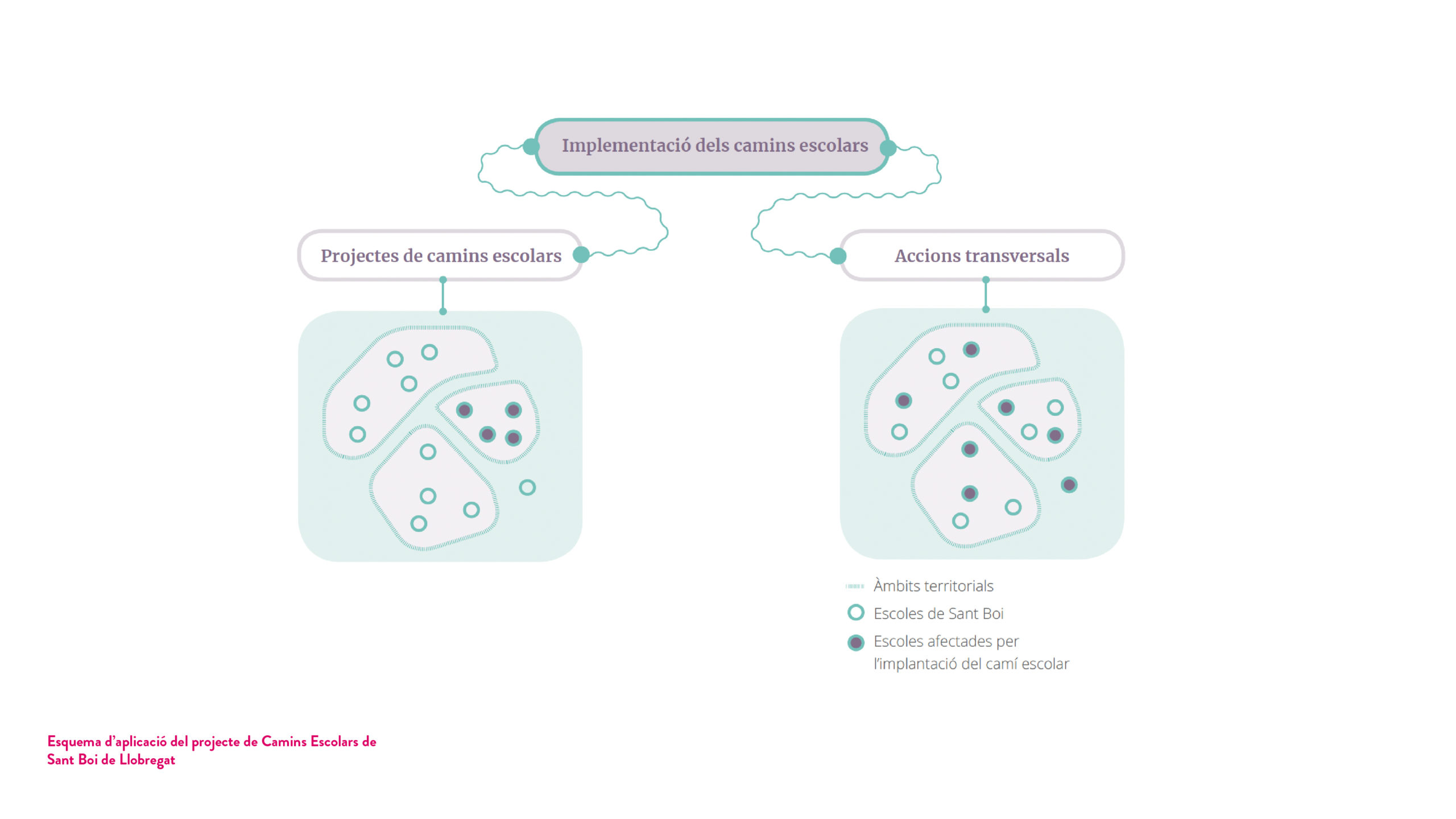

What many associations working to improve the quality of life for dogs, their caregivers, and other citizens, especially in urban environments, are requesting is a reconsideration of the model for dog recreation areas. They aim to move towards a less segregated model, taking into account that dog-owning families may also have children who want to play at the same time. That’s why it is necessary to move towards a model that accommodates different groups in shared-use spaces that adapt to the daily needs of each family.

Moreover, not all dogs feel comfortable in these areas. Speaking with a dog trainer, she mentioned that dog recreation areas are suitable for dogs up to 4-5 years old and typically attract a large number of dogs. Older dogs can feel anxious in these environments, much like how we would feel if we were sent to relax inside a ball pit in a children’s playground. So where do these dogs that don’t enjoy dog recreation areas go?

It’s important to explore alternative options that cater to the diverse needs of dogs, including quieter spaces or alternative socialization opportunities, to ensure the well-being of all dogs in urban settings.

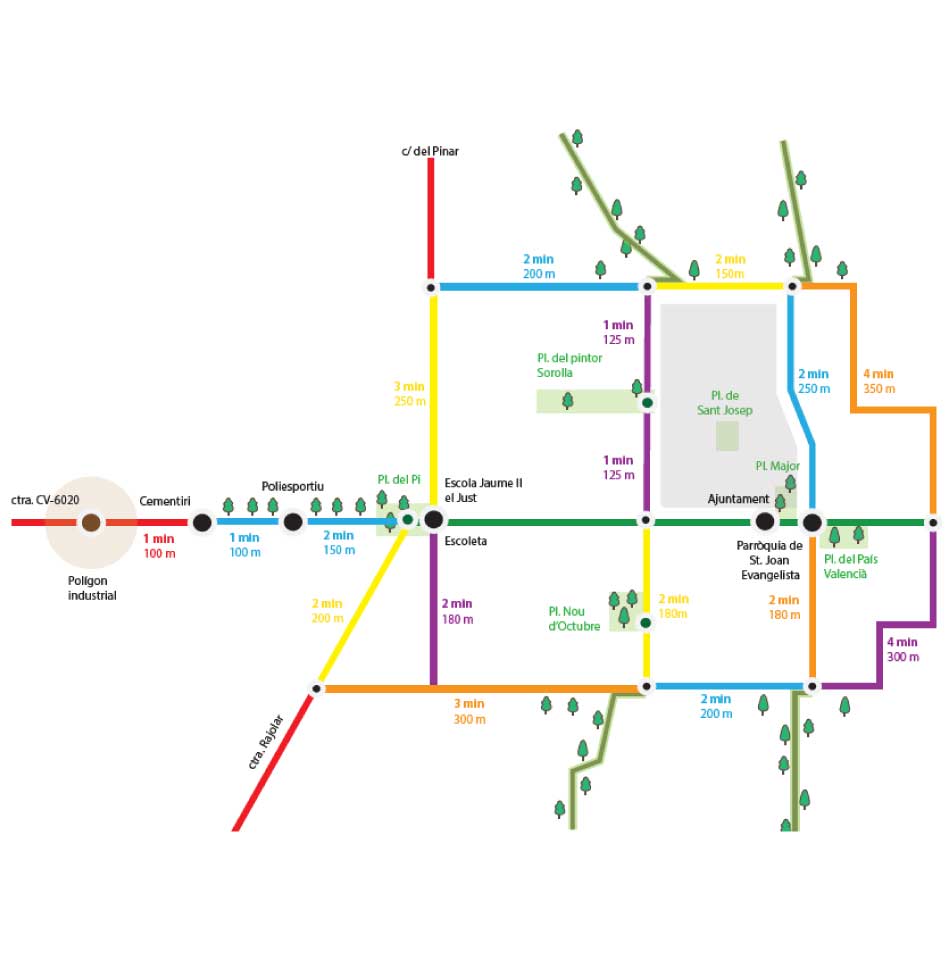

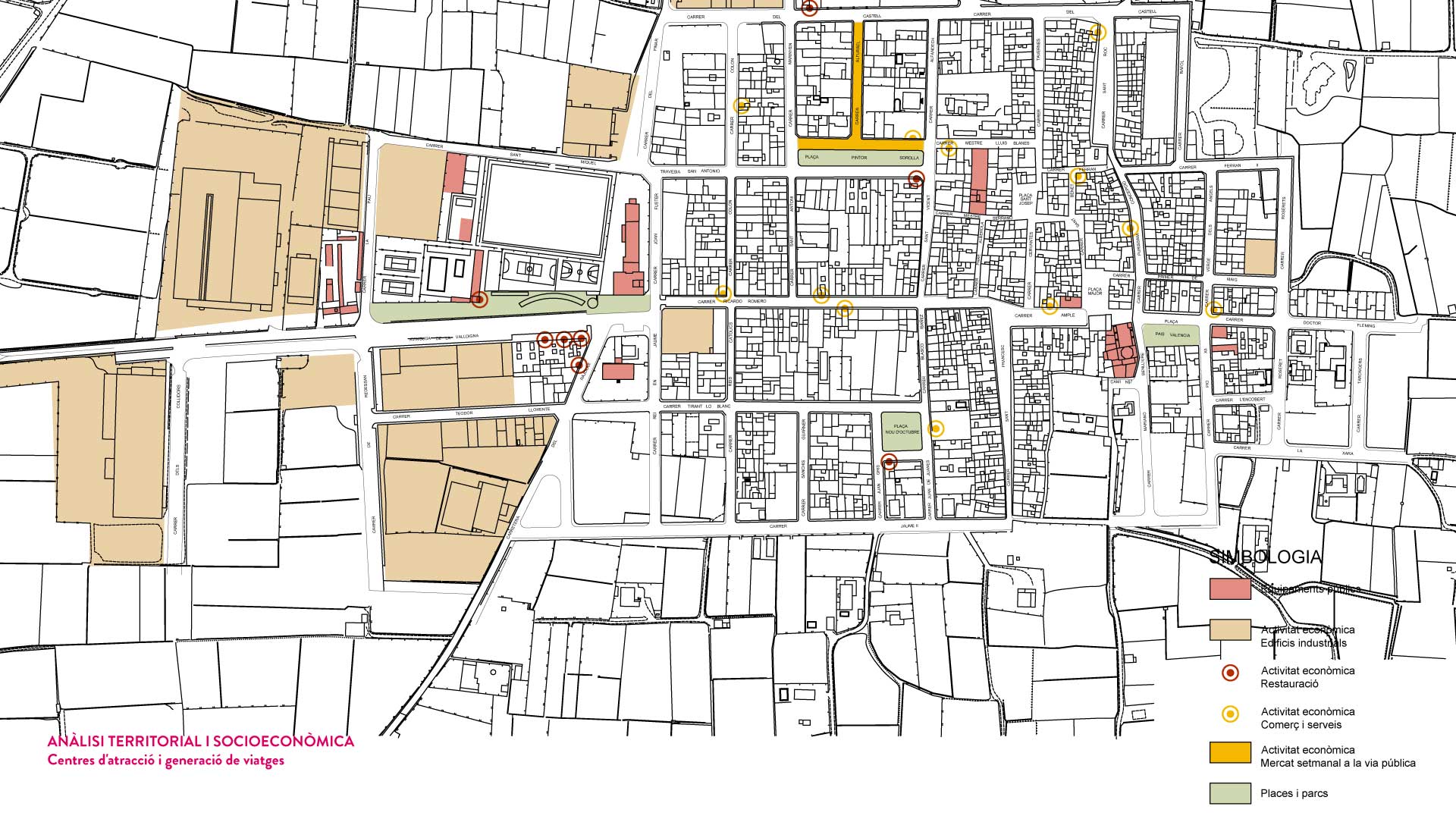

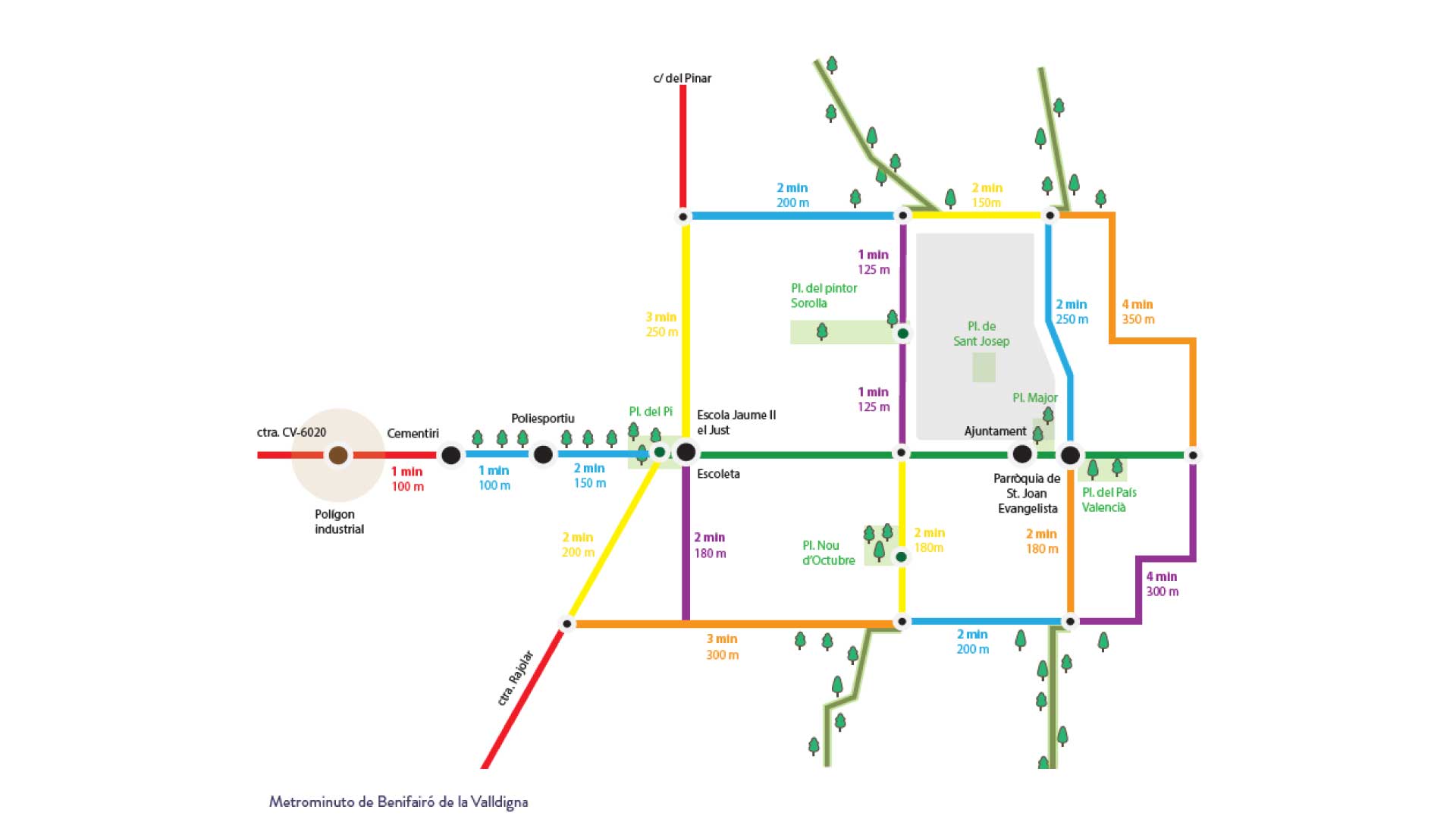

Dog Routes

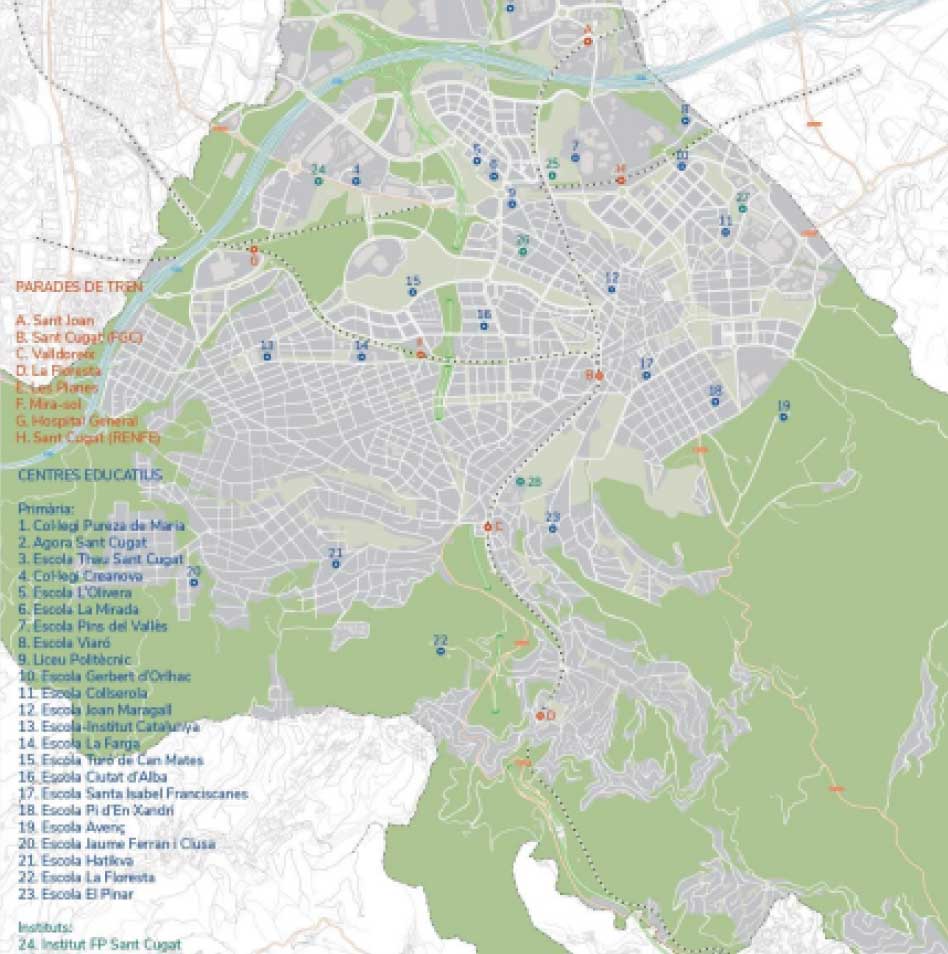

Each neighborhood has an invisible and informal network of dog routes designed for walking dogs, which helps people get out of the house and engage in daily exercise, promoting their mental and physical health. These routes are typically circular, within a 20-minute distance from home, and are chosen for their specific characteristics. A good dog route is pleasant and includes a water fountain, many rubbish bins, permeable spaces and/or green areas, good lighting at night, wide side walks, good visibility, and “dog-friendly” local businesses. Dog routes may vary between winter and summer, as people seek the sun during summer and shade during winter. Canine routes are fully integrated into the 15-minute city model, adding the layer of carrying out daily tasks accompanied by a dog.

The 15-minute city model aims to create more liveable, sustainable, and resilient cities, ensuring that people have access to essential services and amenities within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from their homes. Dogs can play a vital role in supporting this model, as they encourage people to walk more and spend more time outdoors, promoting a healthier and more active lifestyle.

People who walk their dogs often take their animals out multiple times a day, providing them with the opportunity to explore their local neighborhoods, interact with other people and dogs, and discover new parks and green spaces. As a result, dogs can help people discover and connect with their communities, fostering a sense of belonging and improving social cohesion. Furthermore, dogs can help increase the visibility and use of public spaces within the 15-minute city model, such as dog-friendly parks and cafés.

Dogs can also be a tool to promote sustainable transportation, such as walking and cycling, which can help reduce traffic congestion, air pollution, and carbon emissions. This can contribute to a more sustainable and resilient city that is better equipped to address the challenges of climate change.

Overall, dogs can play a crucial role in supporting the 15-minute city model by fostering active lifestyles, reinforcing social connections, increasing the use of public spaces, and promoting sustainable transportation through dog routes.

But what should these spaces be like to ensure quality and improve coexistence?

Design, Maintenance, and Community Involvement

Dog routes, dog parks, and shared-use areas (SUA) must meet certain basic criteria.

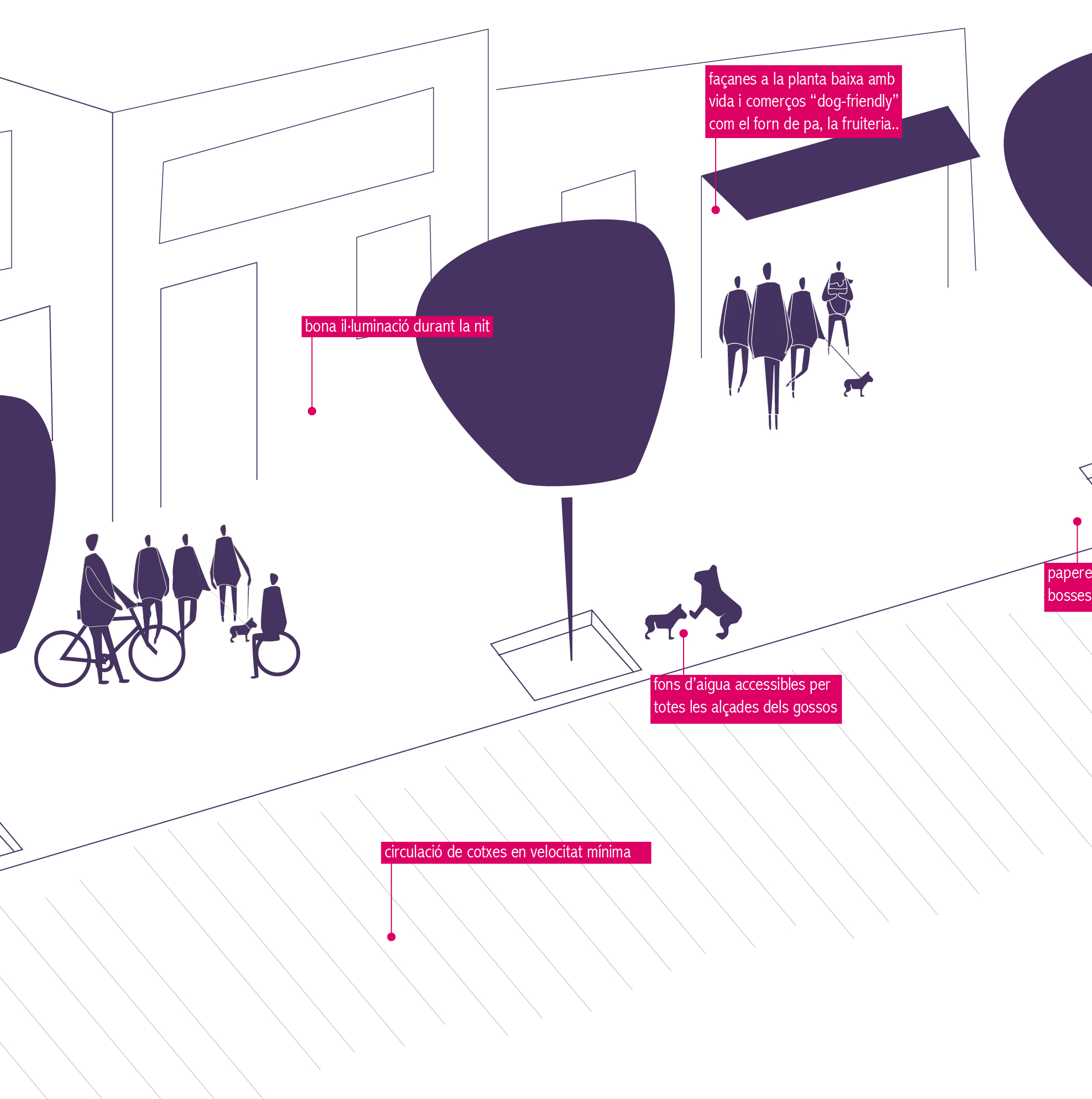

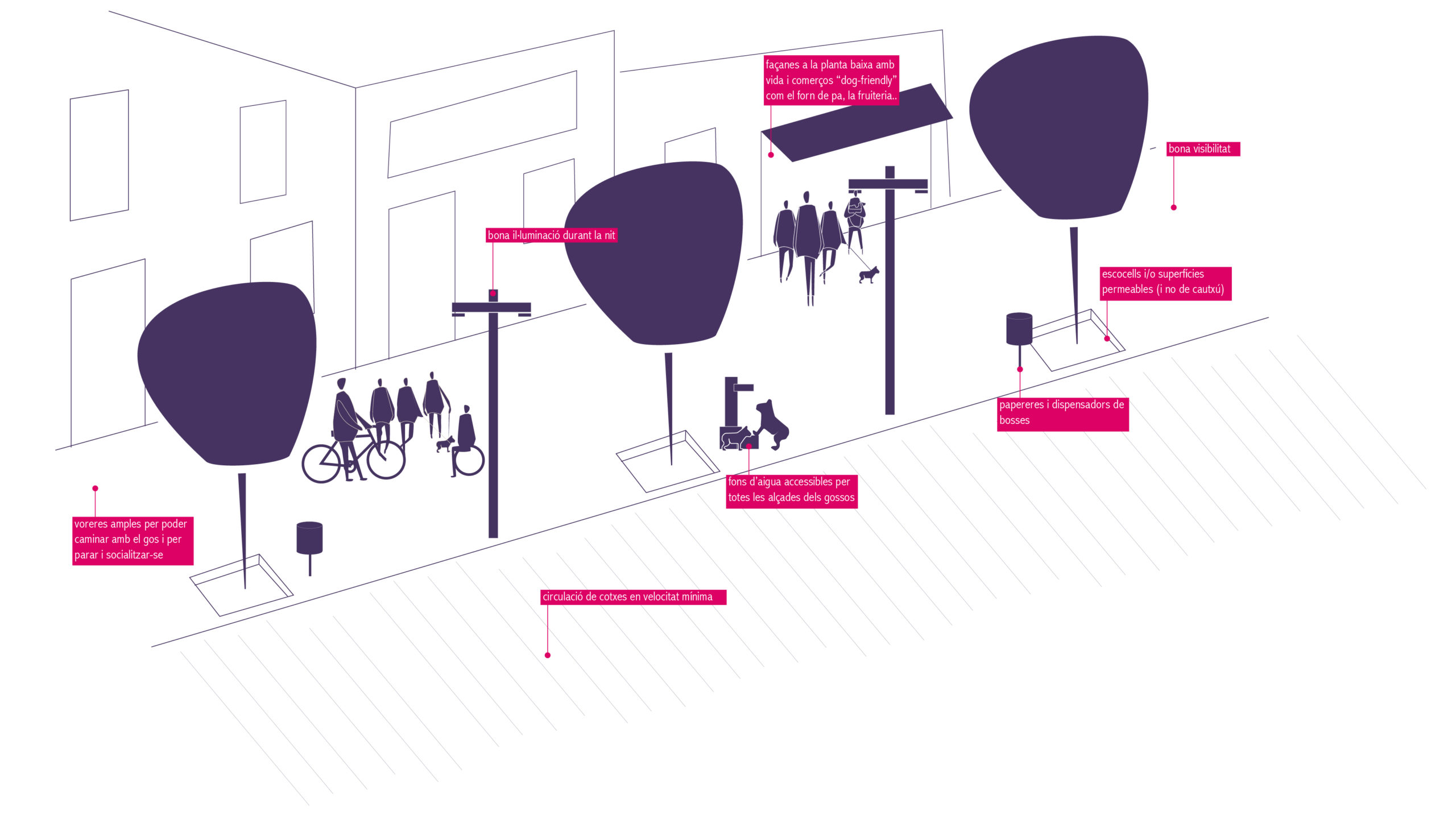

Regarding the daily dog routes, they should be safe, accessible, with plenty of trees and permeable surfaces, and equipped with public amenities to ensure the well-being of dogs, the people who walk them, and the community as a whole. In terms of design criteria for daily routes, they should include:

- Benches and/or permeable surfaces (not rubberized)

- Accessible water sources for dogs of all heights

- Rubbish bins and bag dispensers

- Good nighttime lighting

- Wide side walks for walking the dog and stopping to socialize

- Minimal car traffic speed

- Good visibility

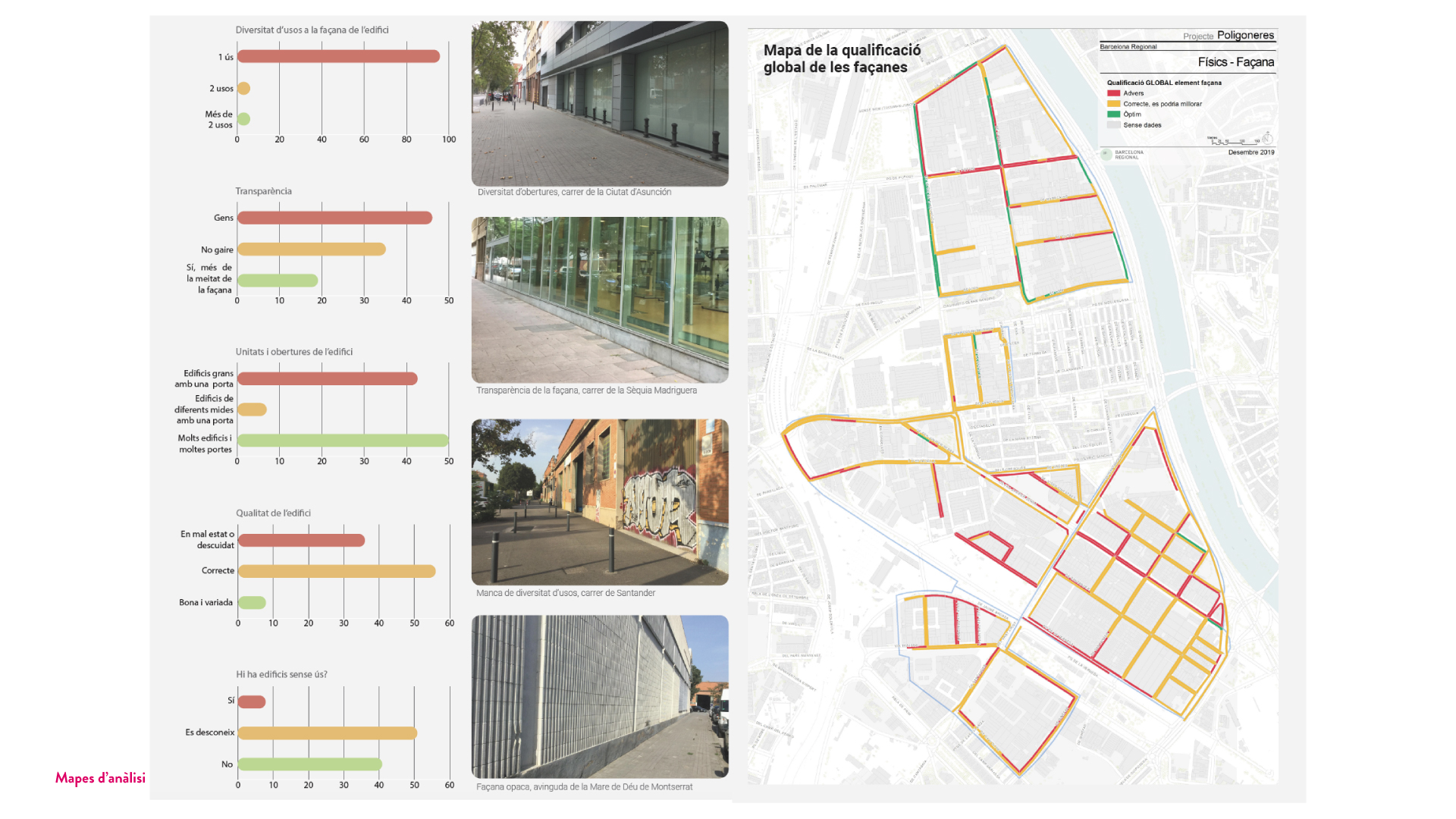

- Ground-floor facades with activity and “dog-friendly” businesses such as bakeries, fruit shops, etc.